Seek modest gains incrementally over colossal gains suddenly

Overview

Some individuals, organisations, and governments attempt to improve their lives or society gradually, incrementally, and continually over time. For example

- every week, an individual might dedicate one hour to a specific pursuit or skill—such as the goal to improve their capability to use generative AI,

- whenever someone leaves an organisation, managers may discuss whether to adjust the roles and responsibilities of staff in the team or maintain existing positions,

- a government might implement a policy that encourages organisations to gradually diminish air pollution over time.

In contrast, other individuals, organisations, and governments prefer more ambitious transformations, designed to improve their circumstances instantly and completely. For instance,

- some individuals might engage a plastic surgeon to transform their appearance considerably,

- an organisation might downsize an organisation by 20%, unaware that such initiatives can promote cynicism and distrust that lasts five years or longer,

- a government might introduce a grand, majestic initiative—such as nuclear energy—to address concerns about energy supply.

These colossal transformations may seem uplifting, but tend to be disappointing or detrimental, for several reasons. First, when people believe they will maintain some activity—such as improve their generative AI skills—over an indeterminate period, they are more likely to thrive. People who strive to improve their life incrementally and continually tend to be more satisfied with life (Shanahan et al, 2024). The reason seems to be that

- these individuals are not as likely to feel divorced or detached from the future,

- instead, they are more inclined to feel their activities now are vital to their lives in the future,

- consequently, these individuals tend to behave more responsibly, diligently, and respectfully rather than impulsively or selfishly.

Second, whenever people experience substantial problems, they would prefer these problems to dissipate rapidly and thus prefer colossal transformations. Yet, in these states, people are especially susceptible to wishful thinking. That is, they are more inclined to overestimate the benefits of these sweeping changes and overlook the drawbacks or complications. In short, a cornerstone of humility is to pursue modest gains incrementally over colossal gains suddenly: a mindset that tends to improve wellbeing and limit disappointment.

How to implement this principle: Bayesian adaptive trials

Problems with many existing practices

When people design an initiative or policy, such as an online module to prevent bullying in students, they tend to underestimate the likelihood of flaws and complications. In practice, these initiatives or policies need to be gradually refined and improved over time as well as adapted to accommodate diverse circumstances, such as children who experience various disabilities.

The problem, however, is that most practitioners—including designers, policy officers, and managers—are not sure how to iterate and to optimise these initiatives over time. For instance, they may not be certain of

- which data should they collect, such as which measures of wellbeing they should measure,

- the amount of data they should collect, such as how often they should collect these data,

- which techniques they should utilise to analyse these data and to inform decisions, and so forth.

Some practitioners simply do not collect or analyse data systematically. Other practitioners might conduct systematic experiments, such as randomised control trials. For example,

- some schools may be randomly chosen to receive the online module,

- other schools may not receive this online module,

- the practitioner can then determine whether the online module diminishes bullying.

These randomised control trials, however, are relatively protracted and inflexible. The practitioner may not be able to complete the analyses within a few months. If the research shows the online module is ineffective, months have been squandered. Many other alternatives, such as step-wedge designs, also tend to be protracted and inflexible.

Example of a Bayesian adaptive trial

According to Cripps et al. (2025), in a recent paper that appeared in the journal Data & Policy, one approach—Bayesian adaptive trials—tends to address many of these concerns and enable practitioners to optimise initiatives and programs iteratively over time (for discussions of this approach in clinical settings, see Spiegelhalter et al., 2004). Here is an example that illustrates the fundamental principles of this approach.

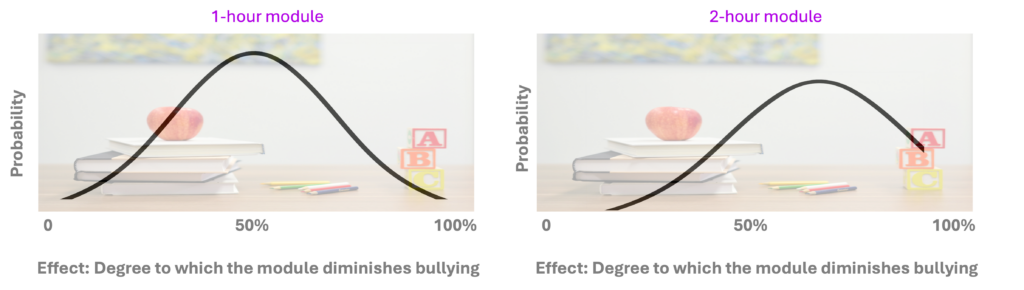

Consider a team of practitioners who want schools to embed an online module, designed to prevent bullying in students, into the curriculum. First, the practitioners utilise their past experience, previous data, and expert opinions to generate what is called an a priori distribution, similar to the following left figure. Specifically

- the horizontal axis represents the actual benefit of this online module,

- the vertical axis represents the probability of this benefit,

- to illustrate, according to this graph, the most likely effect of this module—corresponding to the hump in this graph—is a 50% reduction in bullying.

In practice, the practitioners could generate a family of these probability distributions, depending on some parameter, such as the duration of these modules. For example, according to the previous two figures,

- if the modules last one hour, the most likely effect of this module is a 50% reduction in bullying,

- if the modules last two hours, the most likely effect of this module is a 75% reduction in bullying, and so forth.

Second, the practitioners can utilise these graphs, together with some complicated formulas, to choose, and then to assess, the most beneficial parameter. To illustrate, in this example, the practitioners could

- use the graphs and formulas to identify the duration of these modules that will, most likely, diminish bullying to the greatest extent,

- introduce the online module of this duration, such as 1.3 hours, to a small sample of schools,

- assess the degree to which these modules do indeed curtail bullying.

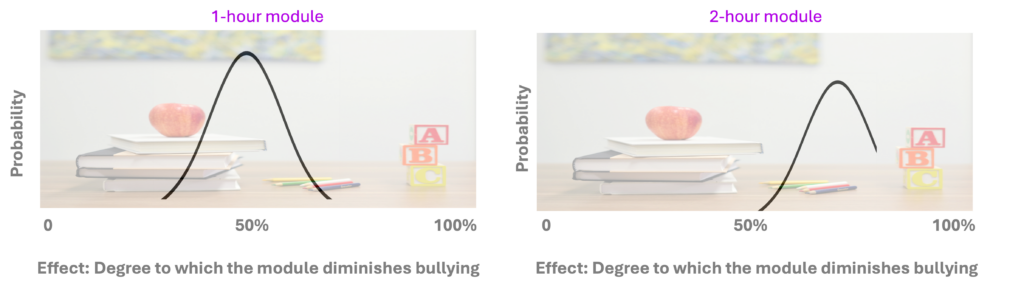

Third, the practitioners can utilise the insights of this short study to update the probability distribution. Specifically, they can utilise various formulas, derived from Bayes theorem, to estimate the probability of various benefits, given the data they received. This procedure might generate some graphs that resemble the following examples.

Fourth, the practitioners could utilise these graphs to change the parameter. For instance, the graphs and formulas may reveal that a duration of 1.5 hours will most likely curtail bullying. Consequently, these individuals can now assess an updated version of these modules that lasts 1.5 hours. Over time, the practitioners can, thus, gradually and continually optimise these modules over time—and can generate distinct probability distributions and parameters for diverse settings. The unique benefits of this approach are that

- practitioners can iteratively refine and improve the initiative over time rather than wait until a large experiment is completed,

- practitioners can adapt the distributions and initiative to suit a range of diverse settings, such as primary schools and high schools,

- this approach may thus encourage more organisations to improve their policies and practices iteratively over time.

The only complication, in practice, is the formulas are hard to utilise, even with the relevant software. Therefore, to apply this approach, practitioners may need to seek the services of specialists in Bayesian statistics.

Example: The four-day work week

Polarising opinions

The four-day work week—although first propounded in the mid 1900s—has sparked considerable interest and polarising opinions more recently, especially since COVID. According to proponents, this arrangement does not only improve the wellbeing and lifestyle of staff but also enhances productivity and efficiency. Indeed, as proponents argue, in at least some sectors, individuals can often produce the same output in four days as they can in five days. Organisations in these sectors can, therefore, afford to reduce work hours by about 20% while retaining existing salaries.

According to opponents, however, the evidence of these beliefs is tenuous (see Campbell, 2024). To illustrate,

- some of the most renowned case studies—such as the trials in a New Zealand financial services firm (Delaney & Casey, 2022), in Icelandic government agencies (Haraldsson & Kellam, 2021), and in the 141 organisations that were reported in Nature Human Behaviour (Fan et al., 2025)—did not report objective measures of productivity,

- some of the benefits could be ascribed to the conversations that organisations convened to identify possible efficiencies before these trials commenced,

- some of the benefits could be ascribed to the promise that such arrangements would continue if productivity was maintained,

- in some instances, other resources, such as government funding, were distributed to offset the impact of this reduction in staff hours.

Potential benefits

Although the evidence is remarkably sketchy, the potential benefits of a four-day work week are remarkably important. For example

- as some evidence indicates, when individuals are granted more time to dedicate towards personal interests or responsibilities, they can more readily detach from their work when needed (Clinton et al., 2017),

- this detachment tends to facilitate sleep (Pereira et al., 2016) and recovery (Wendsche & Lohmann-Haislah, 2017), enhancing the capacity of individuals to mobilise the effort they need at work,

- when individuals feel their work hours are limited, they may be more inclined to mobilise their mental energy rather than maintain a reserve (for mechanisms, see Vohs et al., 2012), enhancing their productivity,

- similarly, when individuals feel their work hours are limited, they may be especially motivated to identify which tasks are most beneficial and thus confine their efforts to more productive activities.

If successful, a four-day work week could also diminish time pressure. When people do not feel as rushed, they become more inspired to learn and to develop (Beck & Schmidt, 2013)—a key determinant of humility. As the level of humility in society increases, many social problems, from domestic violence to driving accidents, tends to plummet.

Government initiatives to assess the impact of reduced working hours

To reconcile this conflict between the potential benefits and the limited evidence of this arrangement, governments could implement a series of three phases. First, the government could fund a project that collates the datasets that are necessary to predict the degree to which a four-day work week may increase productivity and the circumstances that affect this increase. For instance, the recipients of this fund could

- use various datasets, such as ATO data, to ascertain which individuals are working reduced hours,

- for each Australian organisation, utilise this data to estimate increases or decreases to the average working hours of staff each year,

- assess whether these changes in working hours are related to changes in financial performance, such as return on assets,

- determine characteristics of the organisation, such as the sector, that may affect this relationship between changes in average working hours and changes in financial performance.

This project would enable the government to release information on the degree to which a decrease in work hours improves productivity and performance—but customised to the distinct characteristics of each organisation.

Second, the government may then fund a project to estimate the extent to which these decreases in work hours predict improvements in other key social indices—such as measures of life satisfaction, sick leave, and delinquency. If successful, this project could enable the government to

- estimate the degree to which reductions in working hours predicts improvements in these indices,

- estimate the budget the government had previously reserved to enhance these indices to a comparable extent.

To illustrate,

- suppose a reduction in one working hour tends to increase life satisfaction by 10%,

- and suppose the government had planned to fund projects worth $1 billion to increase life satisfaction of employees by 10%,

- therefore, if the government could reduce the working hours of each individual by one hour, they would roughly save $1 billion

- consequently, the government could utilise these savings to subsidise a program that diminishes working hours; the savings and thus subsidy would equal $1 billion x proportion of employees who work one hour less than usual.

In short, if the data do indeed reveal that reductions in working hours improve productivity and other social indices, the government may be able to subsidise organisations that permit these reductions.

Example: Green hydrogen

Concern

To illustrate this principle, consider the government aspirations around the Australian green hydrogen industry. Although touted as an opportunity to diminish carbon emissions in many industrial activities—such as the production of steel, ammonia, and cement as well as the transportation of goods in ships, aviation, or trucks—the industry has stagnated in recent years. As illustrations of this stagnation

- in May 2025, Fortescue retrenched 90 staff whose jobs revolved around green hydrogen,

- in July 2025, the Queensland government withdrew financial assistance of the Central Queensland Hydrogen Hub.

One possible cause of this stagnation is that governments have not prioritised specific industries, such as ammonia production. For example, the Hydrogen Headstart program, launched by the federal government in 2023, subsidies hydrogen projects in all industries. The problem is that

- Australia has not developed the capacity to design, to construct, to commission, and then to manage large green hydrogen facilities; the facilities that produce green hydrogen today are relatively small, producing less than one tonne a day,

- to utilise green hydrogen in facilities that currently depend on other fuels, organisations need to transform their operations appreciably, demanding significant investment,

- and yet, because of uncertainty around green hydrogen, amplified by the costs of this fuel today, organisations are not as willing to invest heavily in this technology.

Recommendation

As Reeve (2025) suggests, Australia should deliberately expand the industry only gradually, prioritising ammonia production or perhaps other industries that demand limited investment from the outset. Once this use of green hydrogen appears to be sustainable, the government could then offer subsidies to expand this technology to other specific industries. If this approach is not adopted

- many existing investments in green hydrogen will continue to be squandered,

- the faith of investors in this technology will subside,

- the potential of this industry in Australia will dissipate, perhaps indefinitely.

Example: Housing construction

In 2025, the Australian Productivity Commission released a report, entitled “Housing construction productivity: can we fix it?” This report underscores some challenges that can unfold when governments introduce changes iteratively. To address these challenges, various measures may thus need to complement initiatives that are implemented gradually and iteratively over time.

The challenges

Many problems in society, from homelessness to inflation, can be ascribed to a limited supply of housing As this report underscores. As this report demonstrates, over the past 30 years, housing construction has become less efficient, both in Australia as well as in many other nations. For example, for each hour that a construction worker operates, the number of dwellings constructed has diminished significantly—by over 50%. Even when other changes, such as the quality or size of houses are controlled, this decline in productivity is still observed.

This decline can be ascribed to a diversity of barriers. These barriers include the large number of regulations that developers must accommodate, rapid changes in these regulations over time, and conflicts between some regulations and potential innovations such as prefabrication (for some possible solutions, see Building Commission NSW, 2024). Most of the constructions firms in Australia are relatively small, magnifying the impact of this regulatory burden.

To boost productivity in housing construction, Australian governments have introduced a raft of policies. To illustrate, in 2011, the government launched the National Construction Code—an extensive series of requirements that all housing must fulfill around safety, accessibility, sustainability, and quality. Second, to coordinate the implementation of these principles more effectively, in 2023, National Cabinet introduced the National Planning Reform Blueprint: a suite of 10 measures and 17 actions to facilitate planning. Despite these changes, many ongoing challenges remain. For example

- businesses need to seek approval from diverse agencies—including departments that manage environmental regulations—and are often uncertain how to coordinate these activities,

- in addition to the National Construction Code, local governments often impose additional rules.

Although most states have recently introduced bodies to help coordinate this extensive set of approvals and related activities, other complications persist. To illustrate,

- many of the agencies or departments that distribute approvals or certificates are understaffed, delaying these activities, despite statutory timeframes and other measures that were designed to address this concern,

- the code is updated frequently—every three years—and sometimes includes changes in which the costs do not outweigh the benefits to society (Productivity Commission, 2025).

How to prevent fragmentation

As these concerns imply, when governments improve a program iteratively—such as the National Construction Code—they often commit several common errors. For example

- governments tend to underestimate the workload and time these changes will demand, called the planning fallacy (Buehler & Griffin, 2015),

- agencies tend to maintain their existing practices, such as the platform they are using, rather than adapt these practices over time to accommodate large changes (e.g., Kahneman et al., 1991).

Accordingly, to improve the National Construction Code or indeed any program iteratively, governments could perhaps co-design, in collaboration with a company, a platform that integrates the various activities as seamlessly as possible. Here are key features of this platform:

- each time the National Construction Code is updated, the developers of this platform would utilise AI to identify, the order in which the various activities—such as the diversity of approvals—should be completed,

- the developers would use data about past delays as well as other information to inform this AI tool,

- to prevent excessive change, most updates to the National Construction Code should be introduced gradually, first as a pilot, then as a recommendation, and finally as a requirement,

- whenever am update is introduced, government agencies should estimate the least number of working hours and the most number of working hours that may be needed to accommodate this change—a practice that has been shown to curb the planning fallacy (Bordley et al., 2019),

- all government agencies that utilise this platform should assign at least one staff member the role to help coordinate these activities and to seek efficiencies with other departments; furthermore, if these agencies are understaffed, these additional staff may be able to assist as well,

- because this platform is a private-public partnership, the private company will be especially motivated to design a platform that is commercially viable and thus attractive to construction companies.

Example: Gradual extension of telehealth.

Telehealth, in which patients interact with health practitioners remotely, has transformed the health sector. Telehealth extends health services to more remote areas, diminishes the time and inconvenience of visits to a clinic, and facilitates a range of innovations. Indeed, as the Productivity Commission (2024) outlined in a report entitled “Leveraging digital technology in healthcare”, for many problems

- clinical outcomes do not differ significantly between telehealth and traditional care in person,

- patients tend to be satisfied with the services they receive from telehealth.

Limitations to telehealth

Nevertheless, because of various regulations, telehealth has not been implemented extensively. For example, at this time, besides a few exceptions, Medicare does not reimburse telehealth appointments with GPs—unless the patient has visited this GP in person within the last 12 months, called the 12-month rule. Unfortunately, because of this rule,

- patients who need to visit their GP only once a year or less cannot utilise telehealth services,

- patients who cannot readily travel to a GP and who cannot afford to pay the fee often forgo these appointments—increasingly the likelihood of more costly health problems in the future,

- patients are more reluctant to switch to another GP, because they would then be ineligible to receive Medicare reimbursements for telehealth.

Because of these consequences, many bodies and commentators have challenged the 12-month rule, maintaining this rule should be applied only in more exceptional circumstances. However, if this rule was discarded swiftly, a range of complications might unfold:

- First, research has not definitively or comprehensively established which health services are better in person or which circumstances affect the impact of telehealth. Therefore, if telehealth proliferated too rapidly, the quality of particular health services may decline significantly.

- Second, if this 12-month rule was relaxed, patients may be more inclined to contact a GP even when this visit is unnecessary, potentially augmenting the costs of healthcare considerably.

- Third, if this 12-month rule was relaxed, patients in remote regions may not be as likely to visit local health centres—and, therefore, the viability of these centres might plummet.

Issues around iteration

Accordingly, the government may need to relax the 12-month rule gradually and iteratively. To illustrate,

- initially, the 12-month rule could be relaxed if the patient receives other Centrelink services,

- gradually, the 12-month rule could be relaxed for services that research indicates are as effective if delivered remotely than if delivered in person.

Nevertheless, to implement these changes iteratively, governments need to recognise and to address some complications:

- First, many initiatives, although initially successful, are ineffective when implemented at scale. Therefore, rather than merely undertake a few pilots and then implement the change fully, this initiative must expand steadily over time.

- Second, during pilots, governments often choose circumstances that are low in risk. However, initiatives that are effective in these circumstances are often ineffective in riskier circumstances. Instead, governments should consider some pilots in risky settings—but in settings in which these risks can be managed swiftly and effectively.