The role of childhood experiences in psychopathy

Overview

Researchers tend to ascribe psychopathy, at least partly, to genes. Nevertheless, studies have explored whether adverse childhood experiences, such as abuse or neglect, may also foster psychopathy. As these studies indicate, adverse childhood experiences are more likely to increase the incidence of some, but perhaps not all, variants of psychopathy. Arguably, these experiences tend to promote variants of psychopathy that coincide with strong negative emotions and impulsive behaviour.

To explore this relationship between childhood experiences and psychopathy, Moreira et al. (2020) conducted a systematic review. The researchers extracted relevant publications from a range of databases, including Academic Search Ultimate, PsycARTICLES, PsycINFO, and Sociology Source Ultimate. To unearth these publications, the researchers entered keywords that were synonymous with

- psychopathy, such as sociopath*, antisocial, and callous*, as well as

- adverse childhood experiences, such as traumatic events in childhood.

To supplement this procedure, the researchers also examined bibliographies and studies that cited the identified publications. This approach uncovered 19 studies that fulfill the selection criteria.

Key results

As the review demonstrated, many studies have revealed an overlap between adverse events during childhood and subsequent psychopathy. For example

- in a community sample of 333 participants, individuals who were separated from their parents before the age of 3 were more likely to exhibit a psychopathic personality in their late 20s (Gao et al., 2010),

- in a sample of incarcerated males, a history of physical abuse, emotional abuse, physical neglect, and emotional neglect were all positively related to psychopathy (Dargis et al., 2016),

- in a sample of violent offenders in Italy, the people who experienced abuse, neglect, or other traumatic events from trusted individuals were more likely to demonstrate psychopathy (Craparo et al., 2013),

- in a sample of adolescents, living in premises that house juvenile offenders or delinquents, high scores on the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire were positively associated with a psychopathy personality (Farina et al., 2018),

- witnessing domestic violence as a child tends to predict many facets of psychopathy later in life, especially the manipulative and callous features—even after controlling direct exposure to abuse (Dargis & Koenigs, 2017a).

Other studies demonstrated that adverse childhood experiences were more likely to promote some facets of psychopathy than other facets. To illustrate

- in a sample of 110 incarcerated men, high scores on the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire were more likely to be observed in participants who scored high on both psychopathy and negative affect than in participants who scored high on psychopathy but not negative affect (Dargis & Koenigs, 2017b),

- in a sample of 615 male offenders, individuals who indicated they had experienced abuse demonstrated lifestyle features of psychopathy—such as impulsive, irresponsible, or criminal behaviour—but not the interpersonal or callous features of psychopathy, such as manipulative behaviour or limited empathy (Poythress et al., 2006),

- in a sample of 78 Italian inmates, emotional abuse was positively associated with multiple facets of psychopathy, especially impulsive lifestyles and callous affect (Schimmenti et al., 2015).

In short, adverse childhood experiences seem to foster psychopathic tendencies in the future—and especially tendencies that revolve around impulsive behaviour or strong negative emotions. Nevertheless, the precise facets of psychopathy that coincide with adverse childhood experiences varies across studies and thus warrants further research. Future research could also overcome another limitation of past studies. Specifically,

- past studies do not often differentiate adverse childhood experiences from genetic influences,

- that is, arguably, the genes of individuals might provoke behaviours that elicit abuse, or other adverse reactions, from parents.

The role of childhood experiences in psychopathy: The dynamic maturational model

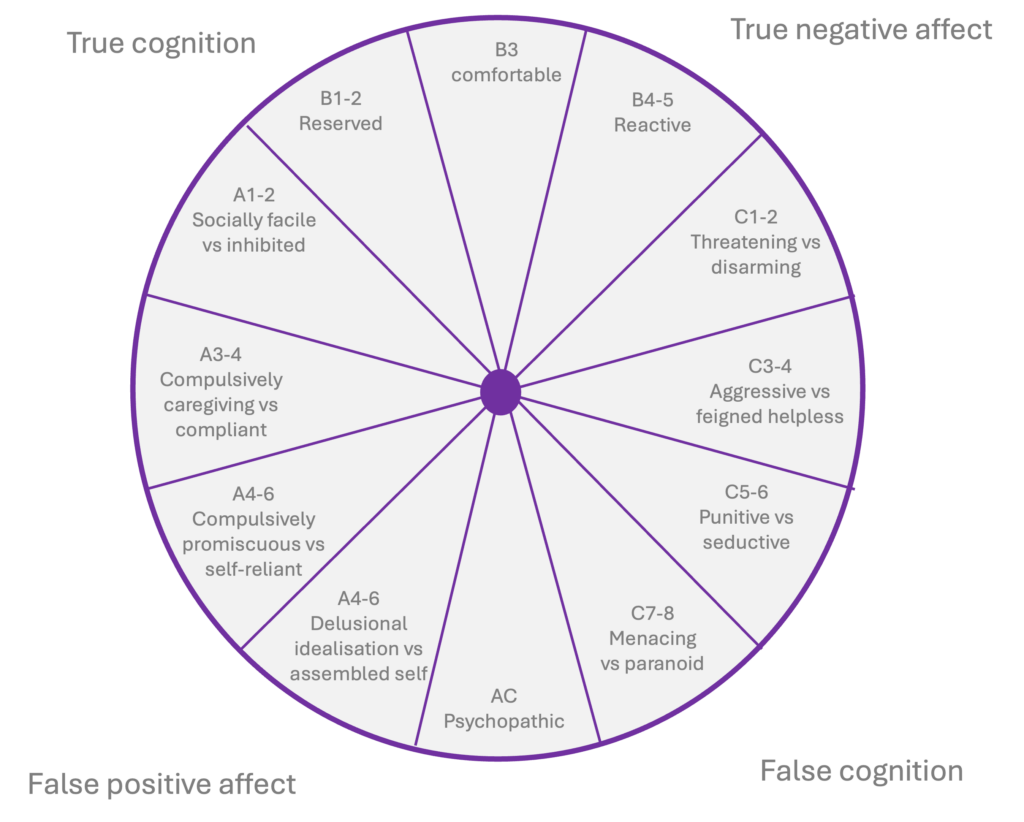

The dynamic maturational model of attachment and adaptation, outlined by Patricia Crittenden (1993, 1995, 2000, 2006), is an extension or variant of attachment theory (see also Crittenden & Spieker, 2018; Landa & Duschinsky, 2013). Patricia Crittenden was a student of Mary Ainsworth. Rather than merely 3 or 4 distinct attachment styles, the dynamic maturational model differentiates 22 patterns of interpersonal behaviour, although individuals tend to apply multiple patterns at any time. The following figure represents these 22 patterns or styles.

Type A or Affective Strategies

The left side of this wheel, especially from A1-2 to A7-8, represent styles that vary according to how children, adolescents, and adults dismiss negative affect during interactions with attachment figures. To illustrate, if their parents are insensitive or dismissive, infants may learn to conceal or dismiss some of the negative emotions that could antagonise these parents. They might, for example, attempt to exhibit positive facial expressions towards their parents or attachment figures, manifesting as insincere or socially facile, corresponding to A1. Or they may abstain from the inclination to express distress, manifesting as inhibition, corresponding to A2. These behaviours evolved to increase the degree to which caregivers are available rather than antagonised. Therefore, these behaviours may be adaptive: They augment the likelihood that caregivers may offer support when needed.

This segment roughly corresponds to infants or children who exhibit an anxious-avoidant strategy during the Strange Situation Procedure (Ainsworth & Wittig, 1969)—children who Ainsworth designated as Type A. Specifically, when their parents leave a room, these children exhibit almost no distress. Later, when the parent returns, these children hardly respond.

As they shift from infancy to childhood, these strategies might persist. The children might apply these strategies during interactions with other individuals. However, if these strategies are not effective, and their attachment figures continue to seem insensitive or dismissive, these children might adapt these strategies—and engage in behaviours that infants cannot initiate. For example, the child might strive diligently to help the caregiver, attempting to enhance the disposition of this person, called compulsive caregiving and corresponding to A3. Alternatively, the child might become intensely obedient, vigilantly acquiescing to the directives of this caregiver, called compulsively compliant and corresponding to A4.

If their attachment figures continue to seem insensitive or dismissive, adolescents are able to develop strategies that are not as dependent upon caregivers. They might withdraw from relationships altogether, and depend on their own skills, corresponding to A6. Instead, they might establish superficial relationships with other people in their life. To minimize reliance on one person, they might gravitate to promiscuous behaviour, corresponding to A5. As they continue to age, if their attachment figures continue to be insensitive or dismissive, their emotions may become entirely divorced from reality. To illustrate, they might completely idealise attachment figures, corresponding to A7, or reject themselves, correspond to A8.

In this side of the wheel, the odd numbers, such as A1 and A3, tend to represent the inclination of individuals to idealise attachment figures. The even numbers, such as A2 and A4, represent the inclination of individuals to minimise the self—such as disregard their inclinations, needs, or values.

.

Type C or Cognitive Strategies

The right side of this wheel, especially from C1-2 to C7-8, represents styles that vary according to how children, adolescents, and adults distort knowledge or beliefs about safety and danger. To illustrate, if caregivers are unpredictable and inconsistent in their support, perhaps because their mood is erratic, infants may feel, on some level, they can prime support and assistance from these attachment figures. To prime this support, they might, to a modest degree, amplify the extent to which they feel resentful or angry, called threatening behaviour and corresponding to C1. Alternatively, they might slightly exaggerate their expression of affect, such as sob, called disarming and corresponding to C2. These strategies are reinforced whenever these figures respond to these cues

This segment roughly corresponds to children who exhibit an anxious-ambivalent strategy during the Strange Situation Procedure (Ainsworth & Wittig, 1969). Specifically, when their parents leave a room, these children exhibit marked distress. Later, when the parent returns, these children might display anger and resentment, but also become clingy.

As individuals age, children can apply a more diverse range of strategies. For example, if the support and availability of attachment figures continue to be inconsistent, children may distort information or knowledge about the causes of events. That is, memories of specific or isolated events, such as occasions in which a parent was neglectful, are more likely to guide their conclusions. Because of these distortions, mild resentment can escalate into aggression, corresponding to C3, and a mildly disarming tendency can escalate into feigned helplessness, correspond to C4. They may be even willing to jeopardise these relationships with attachment figures.

Once they reach adolescence, individuals can understand the perspectives of attachment figures. Therefore, if these attachment figures continue to seem unpredictable and inconsistent, adolescents might attempt to manipulate these individuals. For example, rather than merely behave aggressively, these adolescents might attempt to punish an attachment figure who does not fulfil their desires, corresponding to C5. Likewise, they might attempt to seduce peers to attract support and assistance, corresponding to C6. If these strategies continue to be ineffective, individuals may threaten or fear almost everyone in their life, culminating in menacing or paranoid behaviour. In this side of the wheel, the odd numbers, such as C1 and C3, tend to represent the inclination of individuals to apply aggressive behaviours to coerce their attachment figures. The even numbers, such as C2 and C4, represent the inclination of individuals to amplify their vulnerability to coerce their attachment figures.

.

Other strategies

Individuals who apply A strategies strive to regulate their emotions and, therefore, tend to dismiss affective information—such as information stored in episodic memory or sensory registers. Individuals who apply C strategies tend to magnify their emotions and, therefore, may dismiss factual knowledge about actual sequences of events—such as information stored in semantic memory. In contrast, individuals who correspond to B1 to B5 tend to utilise emotional information and factual knowledge to roughly equal degrees. They are not as inclined to distort their expression of emotions or beliefs about events.

Indeed, B3 roughly corresponds to a secure attachment during the Strange Situation Procedure (Ainsworth & Wittig, 1969). Specifically, whenever their caregiver sits in the room, these children tend to explore the environment confidently. Once the caregiver departs, the child might initially seem distressed, but then will seem content again as soon as this person returns.

Conversely, AC, on the bottom of this wheel, corresponds to circumstances in which individuals inhibit emotional information and distort factual knowledge. Because they inhibit emotional information, they may not appreciate the emotions of other individuals, compromising empathy. Yet, because they distort factual information, they might experience undue resentment to other people. These strategies may culminate in callous and aggressive behaviour, manifesting as psychopathy.

.

Maladaptive behaviours

The dynamic maturational model assumes that all 22 behavioural strategies were adaptive, at least at the time these strategies developed. The model thus conceptualises patterns of behaviour as strategies that individuals developed to accommodate the demands and needs in particular settings—and are thus perceived as adaptations rather than deficiencies (Baim, 2020).

However, as individuals develop, their needs and circumstances change. For example, during infancy and early childhood, children apply interpersonal strategies to protect themselves from danger and to promote the availability of caregivers. From adolescence onwards, they apply interpersonal strategies to seek a reproductive partner as well. Strategies that might have fulfilled one need might not fulfill other needs. Likewise, strategies that might be adaptive in one circumstance might be unhelpful in other circumstances.

To illustrate, if their caregivers were insensitive or dismissive, children may learn to inhibit their emotions. That is, they learn to disengage their attention from their affective experience. This strategy, once reinforced, may persist during their life, perhaps even after they become a parent. This inclination to disengage from emotions might compromise the capacity of these parents to discern, and thus accommodate, the distress of their children (Baim, 2020). Nevertheless, individuals can shift and modify these strategies over time. As people mature, they develop the capacity to contemplate and reflect carefully, potentially developing more adaptive strategies.

.

Implications of the dynamic maturational model

Several practical implications emanate from this dynamic maturational model of attachment (see Baim, 2020; Crittenden, 2006; Wilcox & Baim, 2016; for the implications of this model to assessment, see Crittenden & Landini, 2011). Consistent with this theory, the aim of therapy is to utilise comprehensive and accurate cognitive and affective information, reflectively rather than reflexively, to choose strategies that are suitable to the circumstances. Practitioners cultivate an environment that feels safe to the client and encourages this client to reflect carefully and accurately and to explore more adaptive strategies. Specifically, practitioners encourage clients to develop strategies that are more suited to particular circumstances, guided by accurate rather than distorted or false information.

As many studies have corroborated, interventions that are guided by this dynamic maturational model greatly benefit infants and children (for reviews, see Landa & Duschinsky, 2013). Research also suggests this approach benefits adolescents and adults. Despite this evidence and the merits of this theory in clinical practice, some features of this model have been touted to be speculative (Landa & Duschinsky, 2013).

.

The role of genetics in psychopathy

A systematic review

Many studies have explored the degree to which psychopathy can be ascribed to genetic variations. Accordingly, Moore et al. (2019) conducted a systematic review to ascertain the extent to which genes underpin the callous and unemotional facet of psychopathy. To conduct this review,

- the researchers searched PubMed and PsychINFO to uncover publications in which the keywords were callous and either twins, heritab*, “geneti*, genom*, or epigen*,

- after screening the titles and abstracts as well as extracting publications from reference lists, the researchers unearthed 39 articles that examined the genetic contribution to the callous and unemotional facet of psychopathy.

To estimate the degree to which callous and unemotional tendencies can be ascribed to genes, over 20 studies compared identical twins and fraternal twins on psychopathy. If identical twins are more alike than fraternal twins on psychopathy, this trait can be significantly attributed to genes. To illustrate

- in a sample of 885 pairs of twins from Georgia, aged 4 to 17, the additive genetic effect—roughly equal to the percentage of variance in callous and unemotional tendencies that can be ascribed to genes—was 49% (Ficks et al., 2014),

- in another sample of 626 pairs of twins from Minnesota, aged 7, about 45% of the variance in callous and unemotional traits could be ascribed to genes, as defined by the additive genetic effect (Blonigen et al., 2005),

- in a sample of over 1000 children aged 5, in Sweden, only about 25% of the variance in scores on the Child Problematic Traits Inventory could be ascribed to genes (Tuvblad et al., 2017),

- finally, in another sample of 264 sets of twins or triplets in Texas, about 40% of the variance in scores on the Inventory of Callous-Unemotional Traits could be ascribed to genes (Mann et al., 2005).

As these studies revealed

- the additive genetic effect was usually between 40% and 60%, especially when the participants were older than 8

- this number was higher when the sample was confined to individuals who had demonstrated some behavioural problems,

- only three of the studies showed that a shared family environment may also shape the level of callous and unemotional tendencies,

- the studies did not uncover consistent differences between the genders.

Moore et al. (2019) also uncovered 16 molecular genetic studies that have examined which genetic alleles may correspond to callous and unemotional tendencies (e.g., Brammer et al., 2016; Hirata et al., 2016). Overall, these studies underscore the possible roles of limited serotonin and oxytocin in the evolution of psychopathy. Specifically

- genes that affect serotonin receptors may affect the likelihood of these callous and unemotional tendencies—consistent with the notion that serotonin levels in the blood supply are inversely associated with these traits (Moul et al., 2013),

- however, the association between genes that affect the serotonin transporter gene and these callous and unemotional tendencies did not generate a consistent pattern—possibly because the effect of these genes may depend on the environment,

- genes that affect oxytocin precursors and receptors also seem to affect the probability of these callous and unemotional tendencies.

Diminished physiological responses to stress in psychopathic individuals

Rationale

According to many scholars, psychopathy could emanate from blunted physiological responses to threat (e.g., Patrick et al., 1993; Patrick, 1994, 2001, 2008, 2022; Patrick et al., 1994; Patrick et al., 1997). When most people observe distressed individuals or are exposed to threats, such as an angry person, they experience a particular sequence of physiological responses. The sympathetic autonomic system of these individuals is activated, raising their heart rate, dilating their pupils, and eliciting other changes that facilitate defensive responses. These physiological changes evoke fear, guilt, empathy, and other emotions. These emotions motivate individuals to shun threatening circumstances or prevent antisocial behaviours.

According to many scholars, psychopathy could emanate from blunted physiological responses to threat (e.g., Patrick et al., 1993; Patrick, 1994, 2001, 2008, 2022; Patrick et al., 1994; Patrick et al., 1997). When most people observe distressed individuals or are exposed to threats, such as an angry person, they experience a particular sequence of physiological responses. The sympathetic autonomic system of these individuals is activated, raising their heart rate, dilating their pupils, and eliciting other changes that facilitate defensive responses. These physiological changes evoke fear, guilt, empathy, and other emotions. These emotions motivate individuals to shun threatening circumstances or prevent antisocial behaviours.

Arguably, in people who demonstrate psychopathy, this suite of physiological responses is dampened. Because fear is impaired, these individuals are not as sensitive to punishments, such as reprimands, and thus may not learn to behave appropriately. Similarly, because guilt or empathy is limited, these individuals are more likely to initiate acts that could harm someone else.

Startle reflex: An illustration

As evidence of this perspective, many studies have shown that startle reflexes are blunted in psychopathic individuals. When people are exposed to a sudden, intense stimulus, such as a loud bang, they reflexively initiate a range of behaviours within 30 to 40 milliseconds. For example, they blink, tense their shoulder muscles, and usually flinch involuntarily. These responses facilitate their capacity to respond defensively to threats and dangers.

In a seminal project, Patrick et al. (1993) revealed how psychopathy coincides with a diminished startle reflex. In this study, all 54 male participants were convicted felons. To assess levels of psychopathy, each participant was subjected to the Psychopathic Checklist-Revised. To assess the startle reflex

- each participant was exposed to a random sequence of 27 slides, each of which depict a pleasant, unpleasant, or neutral scene or object, such as a gun or snake,

- at some random time during 67% of these slides, participants were exposed to a loud acoustic burst of sound, designed to elicit a startle response,

- to gauge the responses of participants to these sounds, the researchers recorded the blink response, EMG activity, heart rate, and skin conductance.

The findings revealed that physiological responses were dampened in the participants whose scores on the Psychopathic Checklist-Revised exceeded 30, emblematic of psychopathy. To demonstrate

- in most individuals, the blink was especially pronounced in response to sounds that coincided with unpleasant images,

- however, in psychopathic individuals, the blink was least pronounced in response to sounds that coincided with either pleasant or unpleasant images.

- similarly, in most individuals, EMG activity as most pronounced in response to sounds that coincided with unpleasant images,

- however, in psychopathic individuals, EMG activity was least pronounced in response to sounds that coincided with unpleasant images.

So, most people exhibit a pronounced startle reflex in threatening or distressing circumstances. In contrast, psychopathic individuals do not exhibit a pronounced startle reflex in these conditions.

Startle reflex: A systematic review

Since this study, many researchers have explored the startle reflex in psychopathy across many settings and demographics. Accordingly, Oskarsson et al. (2021) conducted a systematic review of this research. The overall conclusion was that a diminished startle response, especially in threatening or distressing conditions, coincides with specific facets of psychopathy. In particular, according to Patrick et al. (2009), three traits often underpin psychopathy:

- disinhibition—or the inability of individuals to regulate their impulses,

- boldness—a blend of dominance, resilience, and risk-taking,

- meanness—or a tendency to behave aggressively and disregard the needs of other people.

The systematic review showed that a diminished startle reflex is more closely associated with boldness and meanness than disinhibition. To complete this review, the researchers utilised PubMed, PsycINFO, and Web of Science to uncover 40 peer-reviewed empirical studies, written in English that

- were published after 1994,

- measured psychopathy, callous-unemotional traits, conduct disorder, or antisocial personality disorder,

- measured the startle reflex physiologically.

Most studies uncovered some association between psychopathy and the startle reflex. For example

- in a study of 48 females, aged 19 to 44, the diminished startle reflex coincided with primary psychopathy—the selfish interpersonal behaviour and blunted affect—but not secondary psychopathy—the unstable, criminal, and antisocial lifestyle (Verona et al., 2013),

- a similar pattern was observed in a sample of 108 males (Vaidyanathan et al., 2011),

- in a study of 94 male adolescents, aged 12 to 18, the startle reflex was not as pronounced in juvenile offenders who demonstrated conduct disorder or psychopathy (Syngelaki et al., 2013),

- in a study of 54 children, aged 7 to 12, the startle reflex was blunted in participants who exhibited disruptive behaviour disorder without delinquency (van Goozen et al., 2004).

The researchers distilled several informative patterns from these data. To illustrate

- in children, behaviours that overlap with psychopathy—such as callous, unemotional traits, conduct disorder, and disruptive behaviour—tended to be associated with a diminished startle reflex;

- however, if these children had also been exposed to maltreatment, implying their symptoms can mainly be ascribed to challenging home environments rather than genes, this startle response was not as blunted (Dackis et al., 2015),

- in adolescents and adults, this blunted startle reflex was associated with primary psychopathy, such as the callous and unemotional tendencies, but not secondary psychopathy, such as the impulsive behaviour,

- similarly, in adolescents or adults, this blunted startle reflex was associated with measures of boldness, such as tools that measure fearlessness.

The role of parents

In his influential theory, Paul Frick articulated a compelling account of how this insensitivity of children to threat or distress may evolve into psychopathy (Frick, 1998; Frick & Jackson, 1993). Specifically, according to Frick, this insensitivity to threat may not only limit the effects of disciplinary actions may may also shape the behaviour of parents.

Specifically, because children who are insensitive to threats do not adjust their behaviour in response to punishments, parents and other authority figures may experience a range of unpleasant emotions, such as frustration or resentment. Because of these emotions, these authorities may behave punitively or may withdraw their warmth from these children, impairing the relationship. The parents may even display aggression or contempt—behaviours the children may adopt in the future. The impaired relationship and the tendency of children to emulate some of the behaviours of parents may explain many signs and features of psychopathy.

The role of testosterone, cortisol, and serotonin in psychopathy

The complementary roles of testosterone and cortisol

According to the triple balance hypothesis of emotion (van Honk & Schutter, 2006), psychopathic traits can, at least partly, be ascribed to elevated levels of testosterone and low levels of cortisol. When levels of testosterone are elevated, individuals strive to dominate other people and embrace risks to seek immediate rewards (e.g., de Macks et al., 2011; Laube et al., 2020). When levels of cortisol are low, the typical inclination of individuals to be cautious and fearful (van Honk & Schutter, 2006)—and thus prone to flee a stressful event or respond defensively (Terburg et al., 2009)—dissipates. Therefore, the combination of elevated testosterone and limited cortisol elicits aggressive, bold, and fearless behaviour.

More precisely, testosterone and cortisol affect the brain circuits that connect the amygdala and the prefrontal cortex, especially the orbitofrontal, medial, and ventromedial regions. The amygdala (LeDoux, 2007), embedded within the temporal lobes, detects threats and thus can elicit fear. The orbitofrontal, medial, and ventromedial prefrontal cortex (Price, 1999) enables individuals to integrate and to evaluate all the immediate and future consequences of some action—and thus to reach more considered decisions and to override emotional impulses (Volz & von Cramon, 2009).

When cortisol is high, the amygdala and prefrontal regions are connected strongly, primarily because this hormone underpins the inhibition of behaviours (Roelofs et al., 2005). Accordingly, the prefrontal regions can dampen the activity in the amygdala, manifesting as impulse control. When testosterone levels are high, the amygdala and prefrontal regions are not connected as strongly or as efficiently. Activity in the amygdala can thus escalate, amplifying emotions and sometimes manifesting as impulsive aggression. Thus, low cortisol and high testosterone is especially likely to evoke this impulsive aggression (Terburg et al., 2009).

The role of serotonin

According to the dual-hormone serotonergic hypothesis (Montoya et al., 2012)—an extension to the triple balance hypothesis of emotion—even when testosterone is elevated and cortisol is limited, individuals can regulate their inclination to behave aggressively and boldly. That is, individuals can usually anticipate the adverse social or moral consequences of these aggressive and fearless impulses, such as social exclusion or personal shame, derived from social reasoning, moral sensitivity, or empathic concern. Because of these adverse consequences, people can override or inhibit these impulses. However, if their levels of serotonin are also limited, this capacity of individuals to anticipate the adverse consequences and inhibit their aggressive and fearless tendencies may subside (Montoya et al., 2012). In short, high testosterone, limited cortisol, and serotonergic dysfunction may underpin many psychopathic tendencies.

Evidence

Significant research has corroborated some of the key tenets of this dual-hormone serotonergic hypothesis. For example, as research indicates, in community samples and offenders, elevated levels of testosterone coincide with antisocial or aggressive behaviour when cortisol levels are low but not when cortisol levels are high (Welker et al., 2014; but see Armstrong et al., 2021 for some caveats). More specifically, in people who exhibit primary psychopathy, characterised by callous and blunt affect, cortisol levels tend to be low and do not spike appreciably in response to stress.

Other research has verified the role of serotonin in psychopathy. For example, in people who exhibit aggression in response to provocations, called impulsive aggression, a metabolite of serotonin, 5-HIAA, tends to be sparse in cerebrospinal fluid (e.g., Virkkunen et al., 1995; for a meta-analysis, see Moore et al., 2002). This finding implies that serotonergic activity in the central nervous system is limited in people who demonstrate impulsive aggression. Likewise, serotonergic dysfunction coincides with other tendencies that predict psychopathy (e.g., Soderstrom et al., 2001), such as diminished empathy. Similarly, as brain imaging studies reveal, serotonergic dysfunction coincides with impaired connections between the amygdala and prefrontal cortex (e.g., Heinz et al., 2005; Volman et al., 2013)—connections that facilitate the control of emotional outbursts.

These findings, however, need to be interpreted cautiously. Hormone levels fluctuate appreciable across settings and circumstances and, therefore, are hard to assess definitively. Serotonergic activity in the central nervous system can be assessed only obliquely, with reference to genetic variants or measures of serotonin outside the brain.

The role of noradrenaline and the Integrated Emotion Systems theory in psychopathy

Introduction

James Blair formulated an alternative theory of psychopathy that, despite some overlap with the dual-hormone serotonergic hypothesis, revolves around the roles of both the amygdala and noradrenaline in social learning (Blair, 2006, 2007, 2008). Specifically, when people initiate some act that is typically regarded as inappropriate or undesirable, such as theft or abuse, they will usually receive some punishment, such as a reprimand, that elicits unpleasant emotions, from anxiety to shame. Hence, over time, most people learn to refrain from acts that are deemed as socially undesirable.

Both the amygdala and noradrenaline are central to this learning. Specifically, the amygdala receives information from sensory pathways about the stimuli or events, such as theft. In addition, the amygdala receives information from the brainstem or other regions about the emotional aftermath of these stimuli or events, such as the anxiety. Synapses in the amygdala gradually evolve to strengthen the relationship between stimuli and adverse emotions that coincide (Thompson et al., 2008). Therefore, if the amygdala is operating effectively, the stimuli or events should alone activate the emotional response—and this emotional response will guide other brain regions, such as the hypothalamus or prefrontal cortex.

In addition, after the amygdala detects a stimulus or event that could elicit unpleasant emotions, neurons in the central nucleus of this region activate the locus coeruleus (Poe et al., 2020)—a region in the brainstem that is the primary source of noradrenaline. Noradrenaline is released from the locus coeruleus to many brain regions including the amygdala. This noradrenaline magnifies signals that represent threatening stimuli. Therefore, noradrenaline amplifies synaptic plasticity in the amygdala, enhancing the capacity of this region to connect threatening events to unpleasant emotions.

According to the Integrated Emotion Systems theory (Blair, 2006, 2007, 2008), this sequence of physiological operations is blunted in people who exhibit psychopathy mainly because of genetic aberrations. That is, if the amygdala is not activated sufficiently or is insensitive to noradrenaline, individuals do not experience strong unpleasant emotions in response to behaviours that are socially undesirable and thus punished (Blair, Jones, et al., 1997). Hence, even if castigated, mocked or punished, these individuals will continue to perpetrate these undesirable behaviours (Blair, Peschardt, et al., 2006), such as theft, manifesting as psychopathy.

Evidence

As evidence of this model, fear conditioning is blunted in psychopathic individuals. To illustrate, if people tend to experience an electric shock or other aversive experiences in response to some object, the return of this object should elicit fear, manifested as sweaty skin. In psychopathic individuals, this fear response is blunted.

Brain imaging studies also corroborate the Integrated Emotion Systems theory. As functional MRI has revealed, in response to faces that depict fear, amygdala activity is diminished in psychopathic individuals compared to other participants (Blair, Mitchell, et al., 2004). Accordingly, psychopathic individuals may not be as able to recognise or respond to fear in other people, compromising empathy and diminishing sensitivity to suffering.

Treatment of psychopathy: Systematic reviews

Health practitioners, such as psychologists and psychiatrists, have applied a range of techniques and approaches, such as cognitive-behavioural therapy, to diminish symptoms of psychopathy. Many researchers have assessed whether these approaches are effective. In 2002, Randall Salekin, an academic at the University of Alabama, published a sanguine but controversial meta-analysis that demonstrated that some treatments have been effective. Salekin uncovered 42 publications that had assessed whether treatments of psychopathy were effective. Treatments of overlapping disorders, such as antisocial personality disorder, conduct disorder, or oppositional defiant disorder, were excluded from this meta-analysis. The treatments included

- psychoanalytic approaches, sometimes including family members,

- cognitive-behavioural therapy, rational emotive therapy, or psychodrama,

- ECT or pharmacotherapy, such as Benzedrine sulphate, lithium, or SSRIs,

- therapeutic communities, and

- eclectic approaches.

A few studies uncovered no improvement after treatment. For example

- in a study that Whitaker and Burdy (1969) reported, psychoanalysis did not diminish symptoms of psychopathy in one female patient,

- similarly, in a study that Humphreys (1940) published, psychoanalysis did not diminish symptoms of psychopathy in three male patients.

However, many other studies did report some improvements in the behaviour of psychopathic individuals after treatment. To illustrate,

- in some research that Noshpitz (1984) undertook, psychoanalysis, when applied to five psychopathic individuals, diminished aggressive behaviour and enabled these individuals to express guilt and anxiety,

- in a study that Craft (1968) reported, cognitive-behaviour therapy diminished the incidence of future offenses in a sample of 94 psychopathic individuals.

When aggregated, the various treatments diminished sociopathic or destructive behaviour, drug use, alcohol consumption, sensation seeking, impulsivity, and recidivism. In addition, treatments boosted effort at work or school, empathy, communication, and honesty. When the treatment lasted more than 12 months and the patient was under 18, improvements were especially apparent (Salekin, 2002).

A few years later, however, Harris and Rice (2006) expressed concerns about these findings. As these authors observed, in most past studies, the clinicians both gauged the level of psychopathy and assessed the outcomes subjectively rather than administered a valid instrument. The review that Harris and Rice conducted did not uncover definitive evidence that such treatments diminish the incidence of violent behaviour, criminal acts, or other manifestations of psychopathy.

Treatment of psychopathy: The Clearwater program for psychopathic sex offenders

In recent decades, more comprehensive studies have suggested that psychopathic individuals are, at least in some instances, susceptible to treatment. Olver and Wong (2009) conducted a pioneering study that verified the potential benefits of cognitive-behavioural therapy. The participants were 156 Canadian who had been convicted of sex offences and had scored over 25 on the Psychopathy Checklist-Revised.

These participants had all resided in a mental health facility, comprising 48 beds, in which they were allocated to a regime, called the Clearwater program (Nicholaichuk et al., 2000; Olver & Wong, 2013 ; Olver et al., 2009), lasting six to eight months and administered by the Correctional Service of Canada. The program entails the following activities and features:

- A social worker, occupational therapist, psychiatric nurse, or other health practitioner are assigned as the primary therapist of each participant.

- In both individual and group sessions, the therapist will utilise role modelling, role playing, written assignments, and other approaches to extend the cognitive and behavioural skills of participants.

- In groups of 10 to 12, participants also complete treatment modules, each designed to redress attitudes or cognitions that may stem violence, to overcome deficits in intimacy, or to facilitate healthy relationships—comprising video material, group discussion, and exercises.

- Later in the program, participants discuss how they may respond to lapses or other stressful events.

Here are some examples of these modules:

- Participants attend disclosure groups in which they prepare a personal autobiography, identify the thoughts, emotions, and behaviours that coincided with previous sex offences, and design a relapse prevention plan, stipulating coping skills and networks they could utilise to prevent recidivism.

- In some sessions, participants identify unhelpful thoughts or assumptions that could elicit inappropriate behaviours as well as learn how to challenge and manage these thoughts.

- In other sessions, participants learn how to manage anger or similar emotions more effectively—such as watch stressful events from the perspective of an impartial observer.

- Participants also learn social skills, such as how to be assertive rather than aggressive in provocative circumstances.

- Participants also learn relationship skills, such as how to manage loneliness, rejection, and jealousy as well as how to communicate and solve problems effectively.

- Finally, participants develop an appreciation of how their actions have hurt their victims

Olver and Wong (2009) uncovered some key insights from this program.

- First, although level of psychopathy did increase the likelihood of dropout, about 75% of individuals who exceeded 25 on the psychopathy-checklist did complete the program.

- Second, compared to individuals who did not complete the program, individuals who did complete the program were less likely to perpetrate violent acts over the next 10 years.