A quiet ego

Introduction

The notion of a quiet ego encompasses many of the features that epitomise humility. Thus, research into the features, causes, and consequences of a quiet ego should uncover key insights around humility and narcissism. Individuals who experience a quiet ego demonstrate four qualities (Bauer & Wayment, 2008):

- First, when individuals experience a quiet ego, they can observe themselves from the perspective of someone else, objectively and fairly, called detached awareness.

- Second, perhaps because they can observe themselves objectively, they are not as inclined to perceive themselves as special, but instead feel a sense of belonging or affiliation with all humans, called inclusive identity.

- Third, perhaps because of this sense of affiliation with all humans, they are more inclined to consider, rather than dismiss, the perspective of other individuals, fostering compassion.

- Fourth, perhaps because they learn from the perspective of other people, they strive to develop and to learn from their experiences rather than demonstrate their capabilities, called growth-mindedness.

Measures

To measure a quiet ego, participants complete measures of these four qualities. Specifically, to develop this measure, Wayment et al. (2015) first administered a questionnaire to over 300 psychology students at an American university. The questionnaire included measures that may be relevant to the notion of a quiet rather than defensive ego, including

- mindfulness,

- allo-inclusive identity—or feeling of interconnectedness with other people and the natural world more broadly,

- meaning in life and psychological wellbeing,

- humility and wisdom,

- self-compassion, self-esteem, and self-determination

- generativity—or how the behaviours of individuals contribute to future goals, productivity, and advancement,

- personal growth initiative—or the motivation to grow as a person

Next, the researchers conducted a series of factor analyses to identify clusters of items that may correspond to the four facets of a quiet ego: detached awareness, inclusive identity, perspective taking, and growth-mindedness. Three items, primarily derived from a measure of mindfulness (Brown & Ryan, 2003), assessed detached awareness including

- I find myself doing things without paying much attention [reverse-coded]

- I do jobs or tasks automatically, without being aware of what I’m doing [reverse-coded]

- I rush through activities without being really attentive to them [reverse-coded]

Similarly, three items, mainly derived from a measure of allo-inclusive identity (Leary et al. 2008), gauged inclusive identity, comprising questions that indicate, using overlapping circles, the degree to which they feel

- a connection between you and all living things

- a connection between you and a stranger on a bus

- a connection between you and a person of another race

Furthermore, four items, largely derived from the Davis Interpersonal Reactivity Scale (Davis, 1983), measured perspective taking:

- Before criticising somebody, I try to imagine how I would feel if I were in their place.

- When I’m upset at someone, I usually try to put myself in his or her shoes for a while.

- I try to look at everybody’s side of a disagreement before I make a decision.

- I sometimes find it difficult to see things from another person’s point of view [Reverse-scored]

Finally, five items, derived from the personal growth subscale of the psychological well-being scale (Ryff, 1989), assessed growth:

- For me, life has been a continuous process of learning, changing, and growth.

- I have the sense that I have developed a lot as a person over time.

- I think it is important to have new experiences that challenge how you think about yourself and the world.

- When I think about it, I haven’t really improved much as a person over the years [Reverse-scored].

- For me, life has been a continuous process of learning, changing, and growth.

As evidence of validity, Wayment et al. (2015) showed, in two subsequent research studies, that a quiet ego, as gauged by these four facets, was

- positively associated with agreeableness, openness to experience, the inclination to reframe adverse events positively,

- positively associated with the degree to which individuals feel their basic needs, such as the need to experience autonomy, strong relationships, and competence, are fulfilled,

- positively associated with measures of resilience, coping, authenticity, mindfulness, and life satisfaction,

- negatively associated with feelings of hostility, anger, aggression, and entitlement.

This quiet ego scale has been validated in other settings and nations. For example, Bernabei et al. (2024) validated this scale at an Italian university, in which the participants were 160 university students, ranging in age from 20 to 42. The study revealed that a quiet ego was positively associated with measures of resilience, happiness, and psychological wellbeing.

Willingness to engage with differently-minded others

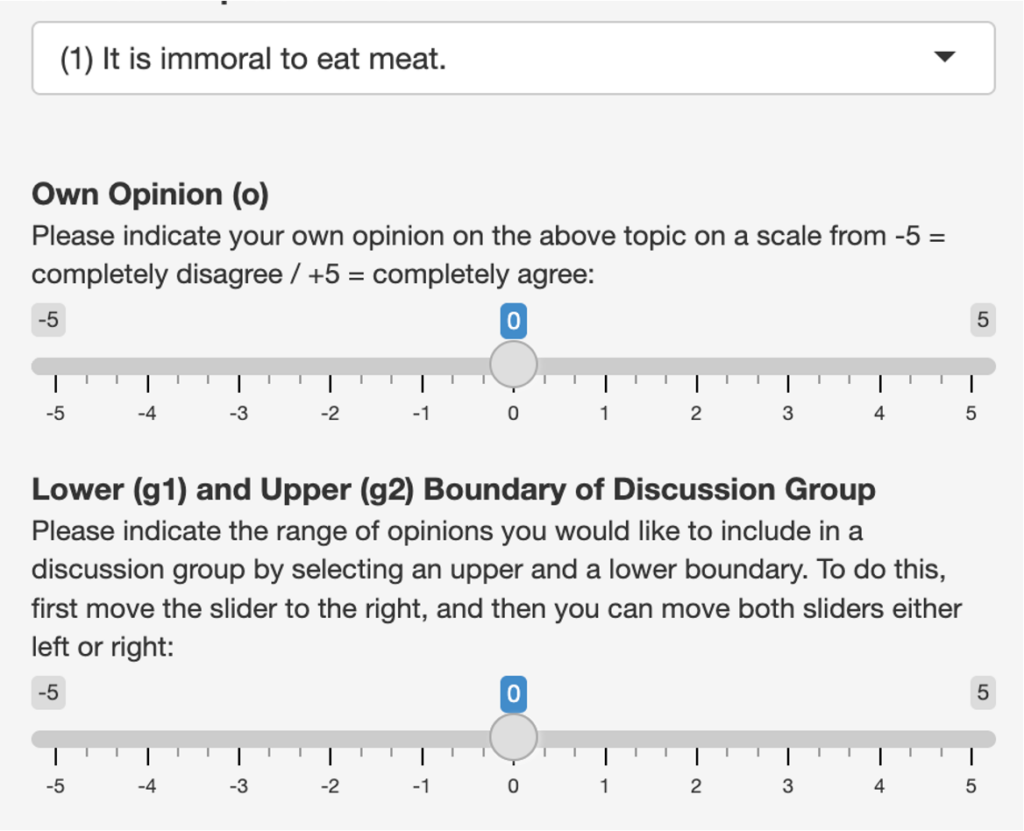

According to Tangney (2000), one of the cardinal features of humility is openness, in which individuals are receptive to ideas or information that contradict their assumptions or preferences. Similarly, Porter and Schumann (2017) revealed that people who are intellectually humble are more inclined than most individuals to consider arguments that oppose their opinions. Accordingly, humble people should feel motivated to approach and to listen to anyone who espouses perspectives that diverge from their own beliefs or desires. In 2025, four Swiss academics, Jauch et al., developed a measure that gauges this tendency, called the willingness to engage with differently-minded others or WEDO. In essence, to assess WEDO, participants complete a sequence of two activities:

- First, participants indicate their opinion on a specific topic, such as the extent to which they agree or disagree on a statement like “To reduce emissions, plane tickets should be much more expensive”. To illustrate, participants might specify 2.3 on a 5-point sliding scale.

- Second, participants imagine they need to assemble a collection of individuals to discuss this topic and then indicate the range of opinions they would like to include in this discussion. For example, they might embrace a range of opinions from 1.3. to 3.5 on the same 5-point sliding scale.

An example of this question appears on a webpage that is publicly available. The following figure illustrates this format.

Empirical evidence

Jauch et al. (2025) conducted a series of studies to validate this scale. In one study, 180 university students, enrolled at the University of Basel, one of the oldest universities in the world, completed the WEDO, in which the topic revolved around sustainability. Furthermore, participants completed a range of other measures such as German versions of

- the Need for Cognition scale, comprising items like “I would prefer complicated problems to easy problems”,

- the Brief Experiential Avoidance Questionnaire (Gámez et al., 2015)—specifically, the distress aversion subscale (e.g., “The key to a good life is never feeling any pain”) and behavioural avoidance subscale (e.g., “I would give up a lot not to feel bad”),

- the categorical thinking subscale of the Constructive Thinking Inventory (Epstein & Meier, 1989), comprising items like “There are basically two kinds of people in this world: good and bad”.

As hypothesised, WEDO, or the willingness to engage with differently-minded others, was positively associated with need for cognition and inversely associated with categorical thinking. However, WEDO was not significantly associated with distress aversion or behavioural avoidance in this study. Subsequent studies demonstrated that

- WEDO is also positively associated with intellectual humility, as gauged the General Intellectual Humility Scale,

- WEDO is positively related to a similar, but more explicit, measure called the Receptiveness to Opposing Views scale (Minson et al., 2020), typified by items like “I am willing to have conversations with individuals who hold strong views opposite to my own”,

- in general, WEDO was associated with the various outcomes, such as intellectual humility and categorical thinking, even after controlling receptiveness to opposing views.

Receptiveness to opposing views

Like the willingness to engage with differently-minded others, Minson et al. (2020) constructed and validated an instrument that gauges the degree to which individuals are receptive to perspectives that diverge from their own beliefs and opinions. This instrument, called the receptiveness to opposing views scale, comprises 18 items and four factors. Participants indicate the degree to which they agree or disagree with these 18 items on a 7-point scale (for a German version, see Kaufmann, 2025). The four factors are

- negative emotions, assessed by four items, such as “Listening to people with views that strongly oppose mine tends to make me angry” and “I feel disgusted by some of the things that people with views that oppose mine say”,

- intellectual curiosity, gauged by five items, such as “I find listening to opposing views informative” and “I value interactions with people who hold strong views opposite to mine”,

- derogation of opponents, corresponding to five items, such as “People who have views that oppose mine rarely present compelling arguments” and “People who have views that oppose mine often base their arguments on emotion rather than logic”, and

- taboo issues, assessed by four items, such as “Some issues are just not up for debate” and “I consider my views on some issues to be sacred”.

People who are receptive to opposing views score high on intellectual curiosity and low on negative emotions, derogation of opponents, and taboo issues. To refine and to validate the instrument, Minson et al. (2020) collected data from six samples of participants. Collectively, as these studies revealed, confirmatory factor analysis did indeed validate the four scales, RMSEA = 0.06, Tucker-Lewis index = .91. Furthermore, if participants were receptive to opposing views, as measured by this scale,

- they were more inclined to access the media releases from a senator who is affiliated with a political party they do not support,

- they were not as likely to feel distracted when observing a speech from a politician who is affiliated with a political party they do not support,

- they evaluated arguments that oppose their beliefs on immigration more impartially, acknowledging that some of these arguments were persuasive and some advocates of these arguments were moral, intelligent, and objective (Minson et al., 2020).

A receptiveness algorithm

Usually, to measure whether people are receptive to opposing ideologies, a researcher will invite participants to estimate their receptivity themselves. For example, participants may be asked to indicate the extent to which they “find listening to opposing views informative”. These self-report measures, however, may be biased or inaccurate. To override this limitation, Yeomans et al. (2020) developed and validated an interpretable machine-learning algorithm that can estimate the extent to which people, during a social exchange, display receptivity to opposing ideologies.

To develop this algorithm, in one study, half the 1102 participants learned about the notion that some people are receptive to opposing ideologies. For example, they were exposed to a sample of questions, derived from the receptiveness to opposing views scale, and informed how a receptive person would answer these questions. The other participants, who had been randomly assigned to the control, read about a species of fish that had recently been discovered.

Next, all participants were invited to indicate the extent to which they agree with a particular stance on a social issue, such as “The public reaction to recent confrontations between police and minority crime suspects has been overblown”. The participants then received a statement, purportedly from another person, that diverges from their position, and were instructed to write a response. Only half the participants were prompted to write as receptively as possible.

Finally, another sample of 1332 individuals read these statements together with the corresponding response. These individuals then evaluated the degree to which the response seemed to demonstrate receptivity to an opposing perspective. These responses and ratings were then subjected to a series of analysis to generate an algorithm. Specifically, the researchers utilised the politeness R package (Yeomans et al., 2018)—a tool that utilises natural language processing models—to ascertain which features of language differentiated responses that were rated as unreceptive from responses that were rated as receptive. The receptive responses tended to include more

- first-person single pronouns, such as “I understand”,

- more agreement, such as “I agree”, even though the statement they received diverged from their opinion,

- more hedges, such as “somewhat” or “may”,

- fewer negations, such as “no”, or “wrong”,

- fewer explanations, such as “because” or “therefore”.

The tool then utilised this information to generate an algorithm estimates the degree to which an excerpt of text displays receptivity to opposing beliefs. To validate this algorithm, the researchers utilised a LASSO algorithm to perform a nested cross-validation. As the results showed, the algorithm could ascertain which of two statement exhibited greater receptivity to similar levels as a human rater (Yeomans et al., 2020).

Although useful, the authors did not publish enough information to enable anyone to utilise the algorithm. Therefore, researchers could either contact the authors or utilise the same methods to develop a similar algorithm.

Wise reasoning

Introduction

Researchers have developed measures to gauge wise reasoning: a state or trait that tends to entail intellectual humility. Many insights about wisdom can be traced to Vivian Clayton. According to Clayton (1983), to solve many problems, individuals merely need to apply a series of rules, logic, and procedures. However, when the problem is not defined unambiguously—such as when the goals are uncertain or conflict with one another—people cannot merely depend on these abilities. Instead, in these circumstances, people need to

- recognise the contradictions or paradoxes that need to be reconciled,

- realise the world changes continuously and thus cannot be fully known,

- offer solutions that accommodate these challenges—skills that epitomise wisdom.

Subsequently, Grossmann et al. (2010, 2013) differentiated some of the key tendencies or abilities that wise people exhibit in challenging social circumstances, such as conflicts. These tendencies include

- intellectual humility or an awareness in people that perhaps their knowledge of a circumstance is incomplete,

- the inclination to adopt the perspective of someone else to appreciate their needs and experience,

- appreciation of the broader considerations in a situation, such as the needs of diverse parties, rather than an obsessive pursuit of personal needs,

- a realisation that a conflict might generate multiple outcomes—and a willingness to compromise to benefit all parties.

Researchers have proposed many other definitions and taxonomies of wisdom. Most researchers, however, acknowledge that balancing conflicting needs—such as dependence and independence—is central to wisdom (e.g., Staudinger & Glück, 2011).

The Situated Wise Reasoning Scale

Brienza et al. (2018) constructed and validated a measure that is designed to assess wise reasoning in a challenging social setting, such as a conflict. To complete this measure, called the Situated Wise Reasoning Scale, participants first recall a specific conflict, disagreement, or similar event. Then, participants answer 21 questions about how they managed this event. These questions assess five distinct factors:

- the perspective of other people, comprising items like “I made an effort to take the other person’s perspective”,

- the possibility of change or multiple outcomes of the challenge, typified by items like “I considered alternative solutions as the situation evolved”,

- intellectual humility, exemplified by items like “I double-checked whether the other person’s opinions might be correct”,

- a search for compromise or resolution, comprising items like “I considered first whether a compromise was possible in resolving the situation”,

- the vantage point of an outsider, typified by items like “I asked myself what other people might think or feel if they were watching the conflict”.

Brienza et al. (2018) undertook a series of studies to validate this measure. One study explored the characteristics or tendencies that tend to coincide with wise reasoning. This study showed that wise reasoning in general and most of the facets in particular, including intellectual humility, are positively associated with

- the belief that conflicts are resolvable and relationships can change and improve over time (for the measure, see Hui et al., 2012),

- a tendency to reappraise circumstances, rather than suppress thoughts, to regulate unpleasant emotions,

- various facets of mindfulness, such as the tendency to observe events like an outsider (for the measure, see Baer et al., 2006),

- features of emotional intelligence, such as the capacity to recognise, utilise, and regulate emotions (for the measure, see Wong and Law, 2002).

Interestingly, wise reasoning tended to diminish with age until individuals reached their mid 40s. After this age, wise reasoning generally improved with age. Finally, wise reasoning predicted the capacity of individuals to balance their own needs with the interests of other parties.g conflicting needs—such as dependence and independence—is central to wisdom (e.g., Staudinger & Glück, 2011).

Epistemic curiosity

Overview

Some people feel a profound desire to accrue knowledge, called epistemic curiosity. Individuals may be motivated to accrue knowledge because

- they are interested or fascinated with extending their knowledge—and enjoy solving intellectual problems and exploring novel ideas,

- they may feel uneasy when their information about a topic is inadequate and thus strive to learn about this particular topic in more detail.

These two tendencies, called diversive and specific curiosity respectively (Berlyne, 1960, 1966), are positively associated with intellectual humility, r = .35 and r = .27 (Leary et al., 2017). Indeed, both epistemic curiosity and humility may correspond to a passion or thirst to learn from other people and experiences.

The epistemic curiosity scale

Litman and Spielberger (2003) constructed and validated a scale, comprising 10 items and two subscales, that assesses epistemic curiosity. Examples of items that assess diversive epistemic curiosity

- I enjoy learning about subjects that are unfamiliar

- I enjoy exploring new ideas

- I enjoy discussing abstract concepts.

Examples of items that assess specific epistemic curiosity

- If I see an incomplete puzzle, I try and imagine the final solution,

- I am interested in solving riddles.

Litman and Spielberger (2003) administered this scale and other related measures to 739 university students. Overall, the findings validate this scale. For example, the overall scale and both subscales were

- positively associated with other measures of curiosity, such as perceptual curiosity (Collins, 1996) and trait curiosity,

- inversely related to trait anxiety,

- positively associated with sensation seeking.

The light triad

Introduction

During this century, many researchers have often examined three traits simultaneously: narcissism, psychopathy, and Machiavellianism. These traits, collectively, are often called the dark triad. Whereas the dark triad predict behaviours that are deemed as socially immoral or undesirable, Kaufman et al. (2019) proposed that researchers should also explore the light triad as well—a set of characteristics that predict behaviours that are socially ethical and desirable. That is, according to the authors, the light triad are not merely the reverse or opposite pole of the dark triad but might entail some other informative tendencies.

Although not the merely the opposite pole of the dark triad, to develop a measure of the light triad, Kaufman et al. (2019) did construct items that seem the converse of behaviours that epitomise narcissism, psychopathy, and Machiavellianism. Ultimately, the authors selected 12 items to measure three distinct subscales or traits. The first trait, called faith in humanity, refers to the extent to which individuals perceive other people as fundamentally virtuous. This subscale comprises four items:

- I tend to see the best in people.

- I tend to trust that other people will deal fairly with me.

- I think people are mostly good.

- I am quick to forgive people who have hurt me.

The second trait, called humanism, revolves around the degree to which individuals appreciate the worth, qualities, and dignity of humans. This subscale also comprises four items:

- I tend to admire others.

- I tend to applaud the successes of other people.

- I tend to treat others as valuable.

- I enjoy listening to people from all walks of life.

The final trait, called Kantianism, concerns the degree to which individuals genuinely enjoy interactions with other people rather than regard people as a means to fulfill some goal—arguably, the converse of Machiavellianism. Four items gauge this trait.

- I prefer honesty over charm.

- I do not feel comfortable overly manipulating people to do something I want.

- I would like to be authentic even if it may damage my reputation.

- When I talk to people, I am rarely thinking about what I want from them.

Validation of this light triad

To validate the measure of these three light traits, in one study that Kaufman et al. (2019) conducted, 670 participants completed this instrument. Confirmatory factor analysis verified these three factors: CFI = .95, RMSEA = .065, STMR = .005. A model comprising only one factor did not achieve an adequate fit: CFI = .78, RMSEA = .127, and SRMR = .089.

To explore the association between these three light traits and other relevant characteristics, Kaufman et al. (2019) collected data from three samples, comprising 670, 237, and 194 participants respectively. Besides the measure of light traits, participants completed a range of other instruments and tasks including

- the SD3 to measure the dark triad of narcissism, psychopathy, and Machiavellianism,

- the Balanced Measure of Psychological Needs Scale (Sheldon & Hilpert, 2012), designed to assess the extent to which individuals feel their basic psychological needs of competence (e.g., “I took on and mastered hard challenges”), autonomy (e.g., “I was really doing what interests me”), and relatedness (e.g., “I felt close and connected with other people who are important to me”) have been satisfied or not,

- the Unified Motives Scales (Schönbrodt and Gerstenberg, 2012) to ascertain the degree to which individuals are motivated to pursue achievement, power, affiliation, and intimacy,

- the Values in Action Brief Strengths Test (Peterson and Seligman, 2004), designed to assess the degree to which participants believe they demonstrate 24 strengths, such as curiosity, love of learning, kindness, honesty, bravery, teamwork, fairness, leadership, forgiveness, and humility,

- the Cognitive Triad Inventory (Beckham et al., 1986), designed to measure the positive or negative beliefs of individuals about themselves (e.g., “I am a failure”), their future (e.g., “Things will never change”), and the world (e.g., “The world is a very hostile place”),

- the Conspicuous Consumption-Extra Money Scale (Lee et al., 2013), in which participants are invited to imagine they had received an extra $100 000 and must decide whether to spend this money on items that are conspicuous or flashy such as luxury cars or premium restaurants, or items that are not conspicuous or flashy, such as health products or insurance,

- the Reactive-Proactive Aggression Questionnaire (Raine et al., 2006), to gauge whether participants tend to exhibit aggression reactively, in response to some provocation (e.g., “When I am teased or threatened, I get angry easily and strike back”), or proactively, (e.g., “I had fights with others to show who was on top”),

- the Selfishness Questionnaire (Raine & Uhi, 2018), developed to measure three facets of selfishness: egocentric (e.g., “I don’t give to charities”), adaptive (e.g., “I have no problem telling white lies if it will help me achieve my goals”), and pathological (e.g., “I’ve occasionally put others down to achieve my goals”),

- a variant of the Dictator Game (e.g., Eckel & Grossman, 1996), in which participants receive a sum of cash and need to decide the amount they will donate to a charity.

In general, the three light traits were inversely associated with the three dark traits, although correlations were not especially high. For example

- the correlations between faith in humanity and Machiavellianism, narcissism, and psychopathy were -0.32, -0.07, -0.31 respectively,

- the correlations between humanism and Machiavellianism, narcissism, and psychopathy were -0.28, -0.07, -0.35 respectively, and

- the correlations between Kantianism and Machiavellianism, narcissism, and psychopathy were -0.44, -0.38, -0.51 respectively,

- accordingly, the three light traits are not merely the opposite pole or reverse of the three dark traits but seem to measure a separate characteristic to some extent.

The three light traits, when combined into a unified score, were moderately associated with various measures of personality. For example,

- the light triad was positively associated with facets of honesty and humility, in which correlations ranged between .22 and .48,

- the light triad was also positively associated with most facets of open-mindedness, conscientiousness, agreeableness, emotional stability, and extraversion—except assertiveness.

The light triad also overlapped with satisfaction of the fundamental psychological needs of competence, autonomy, and relatedness, a key determinant of wellbeing and persistence according to self-determination theory (Deci, Ryan, et al., 2001). That is,

- when scores on the light triad were elevated, people reported greater satisfaction on these fundamental needs as well as experienced the motivation to affiliate with other people,

- in contrast, when scores on the dark triad were elevated, people reported greater dissatisfaction on these three basic needs but also experienced the motivation to seek power over other people.

The light triad also overlapped with many desirable social behaviours. For example, the light triad was negatively, and the dark triad was positively, associated with

- conspicuous consumption,

- reactive and proactive aggression, even after controlling agreeableness as well as honesty and humility,

- all facets of selfishness—egocentric, adaptive, and pathological—even after controlling agreeableness as well as honesty and humility.

Similarly, when playing the dictator game, the light triad was positively, and the dark triad was negatively, associated with the magnitude of donations. Finally, the light triad tended to overlap with measures that often predict wellbeing. For instance

- the light triad was positively associated with life satisfaction, even after controlling agreeableness as well as honesty and humility, whereas the dark triad was negatively associated with life satisfaction,

- the light triad was positively associated with 18 of the 24 character strengths, whereas the dark triad was positively associated with only 6 of these 24 character strengths,

- the light triad was associated with positive attitudes towards themselves, the world, and the future; in contrast, the dark triad was associated with negative attitudes towards themselves and the world.

Incremental validity of the light triad

Researchers have also explored the incremental validity of the light triad. That is, studies have investigated whether the light triad predicts social beliefts or behaviour after controlling the dark triad or other personality characteristics. To illustrate, Lukić and Živanović (2021) examined whether the light triad is associated with worldviews, mindsets, or beliefs that may underpin violent or unsuitable social behaviour. In their second study, 338 individuals completed a suite of measures online including

- the assessment of the light triad,

- the SD3 to measure the dark triad of narcissism, psychopathy, and Machiavellanism—as well as the Varieties of Sadistic Tendencies (Paulhus & Jones, 2015) to measure sadism, sometimes regarded as the fourth trait of the dark tetrad,

- the Competitive Worldview Scale (Duckitt et al., 2002), designed to the degree to which individuals perceive the world as a ruthless battle to secure power, resources, and supremacy, comprising by items like “It’s a dog-eat-dog world where you have to be ruthless at times”,

- the Dangerous Worldview Scale (Duckitt et al., 2002), to gauge the extent to which individuals perceive the world as unsafe and threatening, exemplified by items like “…The world we live in is basically a dangerous and unpredictable place, in which good, decent and moral people’s values and way of life are threatened and disrupted by bad people”,

- the Militant-extremist mindset scale (Stankov et al., 2010), comprising three facets: pro-violence beliefs, such as “Killing is justified when it is an act of revenge”, the perception the world is vile, such as “The present-day world is vile and miserable”, and dependence on divine power, such as “At a critical moment, a divine power will step in to help our people”,

- Generic Conspiracist Beliefs Scale (Brotherton et al., 2013), comprising 15 items that assess susceptibility to conspiracy theories, epitomised by items like “A small, secret group of people is responsible for making all major world decisions, such as going to war”.

The findings verify the incremental validity of faith in humanity but not the other light traits. That is, after controlling the dark tetrad, faith in humanity was inversely associated with competitive worldviews, dangerous worldviews, and the three facets of extremist mindsets—all determinants of prejudice and violence. Humanism and Kantiasm, however, were not significantly associated with these worldviews and mindsets after controlling the other traits.

Non-disclosure of imperfection

The Perfectionistic Self-Presentation Scale

Many people experience perfectionism, in which they set lofty standards and feel shame when they do not fulfill these standards or contempt when other people do not fulfill these standards. However, some individuals are more concerned about whether they are perceived as perfect. Therefore, in 2003, Hewitt et al developed an instrument, comprising three subscales and called the Perfectionistic Self-Presentation Scale, that measures how people manifest or display this perfectionism. Low scores on one of these subscales, the non-disclosure of imperfection, overlaps closely with humility.

The first subscale of the Perfectionistic Self-Presentation Scale is called perfectionistic self-promotion. This subscale assesses the degree to which individuals strive to appear flawless, devoid of imperfections. The subscale comprises 10 items such as

- I strive to look perfect to others

- I must always appear to be perfect

- I try always to present a picture of perfection

- I do not really care about being perfectly groomed [reverse-scored].

The second subscale, called non-display of imperfection errors, gauges the extent to which individuals strive to conceal their mistakes or anxieties. This subscale also comprises 10 items such as

- Errors are much worse if they are made in public rather than in private

- It would be awful if I made a fool of myself in front of others

- I hate to make errors in public

- I do not care about making mistakes in public [reverse-scored].

The third subscale, called non-disclosure of imperfection, measures the degree to which individuals fail to acknowledge personal faults or imperfections to other people (for the Persian version of these subscales, see Kharatzadeh et al., 2025). This subscale comprises only 7 items such as

- I try to keep my faults to myself

- I should solve my own problems rather than admit them to others

- I should always keep my problems to myself

- It is okay to admit mistakes to others [reverse-scored].

Hewitt et al. (2003) reported a series of studies, across seven samples, that validate this measure. For example, the researchers showed that

- the factor structure was the same in a community sample and a student sample—as verified by as coefficients of congruence,

- inter-correlations between the three subscales ranged from .63 to .73,

- all three subscales were positively associated with self-concealment, self-handicapping, attention to comparisons, state anxiety, social phobia, depression, need for approval, and fear of negative reactions,

- all three subscales were inversely related to general self-esteem.

Association with humility

Non-disclosure of imperfection seems to be the reverse of a defining and key feature of humility (Tangney, 2000): the inclination of humble people to acknowledge their limitations and errors. As evidence of this premise

- studies have shown that various measures of maladaptive perfectionism are inversely associated with humility (Feyer et al., 2020; Kamushadze et al., 2021; Thornburg-Suresh & McElroy-Heltzel, 2025),

- as Smith et al. (2016) revealed in a meta-analysis, non-disclosure of imperfection is positively associated with grandiose narcissism and vulnerable narcissism: characteristics that tend to be regarded as the reverse of humility.

Nevertheless, few if any studies have specifically examined the association between non-disclosure of imperfection and humility.

Self-transcendence

According to Tangney (2000), people who are humble recognise they are merely one constituent in a larger universe. That is, humble individuals do not orient their attention only towards their personal needs and concerns but instead are more sensitive and connected to other people, other generations, other species, and the universe in general, sometimes called self-transcendence. This self-transcendence can be regarded as a state of mind, a trait, a capacity that individuals can develop over time, a goal, or a worldview (Wong, 2016)—and may entail mindfulness, flow, awe, mystical experiences, and other states (Yaden et al., 2017).

Developmental models

Some researchers have even developed measures that gauge this self-transcendence. For example, Levenson et al. (2005) developed and validated the adult self-transcendence inventory. This inventory adopts a developmental perspective to characterise the degree to which individuals have become more self-transcendent, and less concerned about their personal needs, over time. This measure comprises 15 items. As factor analysis revealed, ten of the items correspond to a sub-scale called self-transcendence:

- My peace of mind is not so easily upset as it used to be.

- I do not become angry as easily.

- Material things mean less to me.

- My sense of self is less dependent on other people and things.

- I feel much more compassionate, even toward my enemies.

- I am more likely to engage in quiet contemplation.

- I feel that my individual life is a part of a greater whole.

- I feel a greater sense of belonging with both earlier and future generations.

- I have become less concerned about other people’s opinions of me.

- I find more joy in life

Five of the items measure a separate tendency called alienation—a sense of detachment or disengagement from the universe—including

- I feel more isolated and lonely.

- I feel that my life has less meaning.

- I am less optimistic about the future of humanity.

- My sense of self has decreased as I have gotten older.

- I am less interested in seeking out social contact.

As evidence of validity, meditation practice was positively associated with self-transcendence and inversely associated with alienation. Other research has also validated this instrument. For example, Lee et al. (2015) showed that both factors—self-transcendence and alienation—are observed in both the US and Korea.

Aging

Some measures of self-transcendence were derived from the experiences of individuals as they age. For instance, Reed (1986), while employed at the University of Arizona, developed one of the first measures of self-transcendence, sometimes called the self-transcendence scale. The measure was derived from insights about the importance of self-transcendence to mental health, especially later in life. That is, as people age, rather than pursue only goals that relate to themselves—such as identity, reputation, and belonging—these individuals gravitate to values that transcend their personal needs. They may, for example, strive to share wisdom and seek meaning, (Haugan, 2012; Reed, 1986; Reed, 2008). Specifically, this self-transcendence comprises four distinct facets (Reed, 1992):

- the capacity of individuals to develop stronger affiliations with other people and the environment, referred to as the expansion of interpersonal boundaries,

- greater awareness of individuals to their personal values, worldviews, and aspirations, referred to as the expansion of intrapersonal boundaries,

- the capacity of individuals to connect to dimensions that transcend the tangible world, such as spiritual experiences, referred to as the expansion of transpersonal boundaries, and

- the ability of individuals to integrate their past, present, and future lives to generate a meaningful narrative, referred to as the expansion of temporal boundaries.

This self-transcendence is regarded as a resource that individuals can utilise to cope with the challenges they experience, especially as they age. The self-transcendence scale, distilled from a broader measure of resources that older adults can utilise, comprises 15 items. Each item begins with the stem “At this time of my life, I see myself as…” and then specifies a resource such as

- having hobbies and interests I can enjoy,

- accepting myself as I grow older,

- being involved with other people or my community when possible,

- adjusting well to my present life situation,

- adjusting well to changes in my physical abilities

- sharing my wisdom and experience with others,

- finding meaning in my past experience,

- helping others in some way,

- having ongoing interest in learning,

- able to move beyond things that once seemed so important,

- accepting death as a part of life,

- finding meaning in my spiritual beliefs,

- letting others help me when I may need it,

- enjoying my pace of life,

- letting go of my past losses.

According to subsequent research, these items can be divided into either two or four distinct factors or facets (Haugan, 2012). The first factor primarily relates to expansion of interpersonal boundaries, such as “being involved with other people or my community when possible”. A second factor primarily relates to intrapersonal boundaries, such as “finding meaning in my past experience”. The other two factors are not as compelling and comprise fewer items.

ACT and DBT

Some measures of self-transcendence are applicable to specific therapeutic modalities. For example, one instrument was developed to gauge the various facets of self-transcendence that proponents of acceptance and commitment therapy, dialectical behavioural therapy, or similar modalities advocate (Fishbein et al. (2022). Specifically, to experience self-transcendence—a state in which people can separate themselves from their emotional experiences—these individuals may

- cultivate a sense of distance between themselves and the issue of concern, such as a personal challenge or conflict,

- instil the belief that a facet of themselves that observes their behaviour is always present,

- experience a fundamental connection to all beings, called inter-transience.

The ensuing sense of self-transcendence diminishes the impact of unpleasant events, thoughts, or feelings on the experience of people, enabling these individuals to be flexible and resilient.

Fishbein et al. (2022) designed and validated a scale that measures these facets of self-transcendence. The scale comprises three sub-scales:

- distancing, such as “I can observe experiences in my body and mind as events that come and go”,

- observing self, such as “I see a connection between who I am at all places and times”,

- inter-transience, such as “I feel connected even to people I do not know”.

As evidence of validity, Fishbein et al. (2022) also revealed that

- all three subscales were inversely associated with a measure generalised anxiety disorder, indicating that self-transcendence may override feelings of anxiety,

- all three subscales were positively associated with a sense of meaning in life.

Other approaches to measure self-transcendence

Besides questionnaires, researchers have utilised a range of other approaches to measure self-transcendence. As one review, published by Kitson et al. (2020) uncovered, these approaches include

- proxy measures, such as the degree to which time feels slower than usual (Rudd et al., 2012),

- physiological measures—such as measures of goosebumps or piloerection to assess feelings of awe (Benedek et al., 2010) or facial EMG to gauge other self-transcendent emotions (Clayton et al., 2021).

Measures of dialectical thinking

Some people tend to think dichotomously, in which they tend to classify objects or items into two categories, such as moral and immoral, and disregard nuances. Other people tend to think more dialectically in which they do not classify objects or items into two categories but recognise nuances, graded variations, and contradictions. Dialectical thinking is highly related to intellectual humility, as O’Connor et al. (2025) demonstrated empirically. That is, if people think dialectically,

- they recognise their beliefs may not necessarily be right or wrong,

- instead, they realise both their beliefs and contradictory beliefs could both be valuable and, to various extents, accurate,

- consequently, these individuals are more inclined to respect and to consider perspectives that diverge from their opinions, manifesting as intellectual humility.

The dialectical self-scale

Researchers have developed and utilised a range of tools to measure dialectical thinking in various settings. One scale, outline by Spencer-Rodgers et al. (2015), but developed in the early 2000s, is called the dialectical self scale. This scale measures the tendency of some people to think dialectically about themselves rather than dialectically in general. Participants indicate the degree to which they agree or disagree with 32 statements. Factor analysis has uncovered three factors. The first factor, called contradiction, corresponds to the degree to which individuals recognise and accept contradictions in life. Sample items include

- I sometimes believe two things that contradict each other,

- Believing two things that contradict each other is illogical [reverse scored],

- When I hear two sides of an argument, I often agree with both,

- For most important issues, there is one right answer [reverse scored].

The second factor, called cognitive change, corresponds to the extent to which individuals recognise and accept their beliefs may change over time and across settings. Typical items include

- I often find that my beliefs and attitudes will change under different contexts,

- I find that my values and beliefs will change depending on who I am with,

- My core beliefs do not change much over time [reverse scored],

- If I think I am right, I am willing to fight to the end [reverse scored].

The third factor, behaviour change, corresponds to the degree to which individuals recognise and accept their behaviour may change over time and across settings. Sample items include

- I am constantly changing and am different from one time to the next,

- I sometimes find that I am a different person by the evening than I was in the morning,

- I believe my habits are hard to change [reverse scored],

- My outward behaviours reflect my true thoughts and feelings [reverse scored].

Spencer-Rodgers et al. (2009) collected data that corroborates the validity of a version that comprises only 14 items. The sample comprised 129 Asian American students, 115 European American students, and 153 Chinese students. Confirmatory factor analysis substantiated the three factors, in which CFI = .82, GFI = .93, RMSEA = .075, and all factor loadings exceeded .28. Dialectical thinking about the self was lowest in the European Americans relative to the other samples, as hypothesised, but positively associated with anxiety and depression.

The zhong-yong practical thinking scale

Whereas the dialectical self-scale measures the tendency of some people to think dialectically about themselves, the zhong-yong practical thinking scale, comprising 9 items, roughly measures dialectical thinking more generally (for the Chinese version, see Zhang et al., 2011). Specifically, this scale gauges the zhong-yong thinking style: in which individuals contemplate matters carefully from multiple perspectives. Each item comprises two contradictory sentences, one of which epitomises dialectical thinking, such as

- it is important to live in harmony with people around you,

- sometimes you must go ahead regardless to strive for vindication.

Participants first choose which of these two sentences they prefer and then indicate, on a 6-point scale, the degree to which they agree with this chosen sentence. Researchers have also developed several alternative measures of zhong-yong practical thinking (e.g., Li & Chen, 2014). To illustrate, Wu and Lin (2005) develop a version of this instrument, called the Zhong-Yong Thinking Scale, comprising 14 items and three sub-scales:

- multi-thinking or contemplating events from diverse perspectives, such as “I usually think about the same thing from different perspectives”,

- holistic thinking or integration of multiple perspectives, such as “I will adjust my original idea after taking into account the views of others”, and

- harmoniousness, such as “When making a decision, I will consider the harmony of the whole”.

As evidence of validity, when participants report elevated levels of zhong-yong thinking, either using this scale or adapted versions of this scale

- these participants are more able to shift their perspectives and thoughts in response to changes in their environment or circumstances, facilitating resilience (Wang & Yu, 2024)—as measured by items like “I have the self-confidence necessary to try different ways of behaving” (derived from Martin & Rubin, 1995),

- these participants are more inclined to pursue their values persistently, despite emotional challenges (Wang & Yu, 2024),

- partly because of this flexibility, these participants are more able to adapt effectively in social settings (Wang & Yu, 2024),

- these participants are more likely to share knowledge in workplaces (Fan, 2021), as gauged by items like ““I share useful work experience and know-how with others” (Lu et al, 2006), presumably because they embrace diversity and pursue harmony,

- these participants are more likely to suggest creative solutions (Fan, 2021).

The Dialectical Thinking Scale: Dialectical thinking from the perspective of DBT

The capacity of individuals to think dialectically is vital to a specific therapeutic modality called Dialectical Behavior Therapy or DBT. Therefore, Soler et al. (2025) developed a scale—called the Dialectical Thinking Scale—that DBT therapists can utilise to measure dialectical thinking. Although researchers can administer the scale to measure dialectical thinking in other settings, the instrument is especially relevant to health settings because

- the measure is short and thus especially applicable when participants are likely to answer these questions repeatedly,

- some of the questions revolve around personal challenges or problems.

The scale comprises two subscale. The first subscale, called both sides, comprises two items:

- I think there is more than one way to look at a situation and solve a problem

- I can see that two opposing points of view can both be legitimate.

The second subscale, called both sides in me, comprises three items:

- At this point, I could focus on solving the problems I face while accepting the part of them that cannot be changed.

- I can accept my feelings and still pursue my goals.

- I can be independent and also ask for help.

To establish validity, the responses of 205 participants were subjected to a confirmatory factor analysis. The model, comprising two factors, was adequate: CFI = .96, SRMR = .04, and all standardised factor loadings exceeded .58. Furthermore, 15 individuals completed this scale before and after a DBT intervention, lasting 12 weeks. The intervention did significantly improve dialectical thinking, as measured by this scale, to a moderate extent. Finally, responses to this scale and both subscales were inversely associated with depression, hostility, interpersonal sensitivity, phobic anxiety, and psychoticism—as measured by the Spanish version of the Symptom Assessment-45 Questionnaire (Sandín et al., 2008).

Measures of psychological safety

The overlap between psychological safety and humility

Psychological safety and humility, although distinct, overlap considerably. To illustrate, some of the items that measure psychological safety assess

- the extent to which individuals feel their colleagues embrace diverse ideas or perspectives, such as “People on this team sometimes reject others for being different” [reverse-scored]

- the degree to which individuals feel their colleagues appreciate the qualities of other people, such as “Working with members of this team, my unique skills and talents are valued and utilised”

- the extent to which individuals are willing to acknowledge they need assistance, such as “It is difficult to ask other members of this team for help” [reverse-scored].

These facets of psychological safety resemble three of the six defining features of humility, as Tangney (2000) delineated:

- openness to diverse ideas or even information that contradicts preconceptions,

- appreciation of the value and qualities of other people or experiences,

- acknowledgment of limitations, uncertainty, and problems.

Accordingly, psychological safety may overlap with humility. Alternatively, psychological safety may be the state that fosters or enables humility.

The Edmondson (1999) measure and derivatives

A variety of instruments have been developed to assess psychological safety. Edmondson (1999) constructed the first measure of psychological safety in teams. This measure comprises only one factor or dimension and seven items.

- If you make a mistake on this team, it is often held against you [reverse-scored].

- Members of this team are able to bring up problems and tough issues.

- People on this team sometimes reject others for being different [reverse-scored].

- It is safe to take a risk on this team.

- It is difficult to ask other members of this team for help [reverse-scored].

- No one on this team would deliberately act in a way that undermines my efforts.

- Working with members of this team, my unique skills and talents are valued and utilised.

Some of the subsequent measures have adapted and even shortened this instrument. For example

- Detert and Burris (2007) distilled and adapted three of these items to develop another measure of psychological safety—except the items do not refer to the team,

- Carmeli et al. (2010) utilised five of the items that Edmondson (1999) had developed—but referred to the organisation instead of the team.

Other measures

In contrast, May et al. (2004) constructed distinct items to develop a short measure of psychological safety. The items were “I’m not afraid to be myself at work”, “I am afraid to express my opinions at work [reverse-scored]”, and “There is a threatening environment at work” [reverse-scored]. As evidence, of validity, trusting relationships with supervisors and peers fostered psychological safety, as gauged by these three items.

Finally, Liang et al. (2012) also designed a short measure of psychological safety, comprising five items. Typical items were

- In my work unit, I can express my true feelings regarding my job,

- In my work unit, I can freely express my thoughts, and

- Nobody in my unit will pick on me even if I have different opinions.

Meta-analysis of the measures

In a meta-analysis, Liu et al. (2024) assessed this range of measures. Across 217 studies, research indicates that Cronbach’s alpha for these scales ranges from .77 to .84, indicating the items are internally consistent and reliable. Furthermore, as evidence of validity

- all five measures are positively associated with a sense of belonging to the organisation,

- four of the measures are positively associated with trust and a supportive team climate; researchers have not assessed whether the Carmeli et al. (2010) measure is related to this trust or support.