Overview: Kind of humility

Many scholars, researchers, commentators, and other individuals champion the benefits of humility. Yet these individuals seldom agree on the precise definition of humility. One hazy definition may be that humble people

- acknowledge, explore, and embrace their limitations and shortcomings—as well as their strengths,

- appreciate other people and perspectives,

- integrate these insights with their existing beliefs, values, capabilities, and tendencies.

Although helpful, this definition does not encapsulate the many variants of humility that scholars have delineated. Over the last couple of decades, scholars have differentiated many variants, including

- intellectual humility, sometimes conflated with epistemic humility—or roughly the tendency of individuals to appreciate the limitations in their knowledge and beliefs as well as a willingness to shift these beliefs in response to additional evidence,

- moral humility—or the inclination of some people to recognise their beliefs about which actions are right or wrong may be incorrect and to be receptive to other perspectives (Smith & Kouchaki, 2018),

- relational humility—or the willingness of individuals to regulate their personal needs or emotions to improve relationships and accommodate the needs of other people (Davis et al., 2011),

- political humility—or the capacity of individuals to consider the merits and drawbacks of their political opinions and to be receptive to other ideologies (Hodge et al., 2021),

- cultural humility—or a receptivity to other cultural perspectives,

- racial humility—or the ability of privileged communities, such as white people in many societies, to recognise they are not the default race and the perspectives of other races are equally valid and significant (e.g., DiAngeglo, 2018),

- ecological humility—a label to describe people who interact humbly with the resources of this planet (Narvaez, 2019),

- existential humility—a description of individuals who contemplate their role or place in the universe (Van Tongeren, 2022),

- general humility: a form of humility that encompasses all these facets.

The terms humble and humility evolved from two related Latin words: humus, representing the Earth, and humilis, referring to objects on the ground. In this sense, humility refers to people who are grounded in contrast to individuals who think too highly of themselves.

Controversies around these definitions

Michalec et al. (2021) raises some concerns about definitions of humility and attitudes towards humility. Specifically, as these scholars argue, in many strands of literature, such as positive psychology, humility is defined from a Eurocentric or Western perspective. These definitions may, often inadvertently, but perhaps sometimes deliberately, be designed to maintain the existing hierarchies and subjugate other races, ethnicities, or communities (see DiAngelo, 2018; Paine et al., 2017). To illustrate these definitions may

- imply that humility is a virtue,

- suggest that humility may coincide with a docile or even meek demeanour,

- thus impede the attempts of communities to challenge the status quo and seek justice.

General humility

Even the definitions of these variants of humility remain contentious. For example, June Tangney (2000), from George Mason University, in her review of general humility, depicted some diverse and conflicting definitions that scholars and researchers have proposed. From this review, she extracted six cardinal features of general humility (see also Tangney, 2002):

- accurate self-assessment: humble people tend to evaluate their achievements and capabilities accurately,

- acknowledgment of limitations: humble people can acknowledge their errors, shortcomings, uncertainty, and other limitations,

- openness: humble people are receptive to ideas or information that contradicts their assumptions or preferences,

- perspective: humble people recognise they are merely one person in an enormous, interconnected world and thus do not inflate their significance to society,

- limited self-focus: humble people do not consider only their own needs or perspective—but consider the needs and perspectives of other people and the universe more broadly,

- appreciation: humble people appreciate the value of other people, objects, and experiences.

To help characterise humility, Tangney also clarified the characteristics that do not define this quality. Specifically

- humility should not be equated with a low self-esteem,

- people who are humble do not underestimate their capabilities, achievements, or worth to society,

- humility is broader than modesty—because modesty may overlap with only the first two features of the previous definition,

- humility is not merely the absence of narcissism, because some individuals who are not at all narcissistic do not necessarily exhibit all the hallmarks of humility, such as perspective or appreciation, as defined in the previous definition.

Intellectual humility

Roughly, intellectual humility is the tendency of individuals to recognise the limitations in their knowledge and beliefs as well as shift these beliefs in response to additional evidence. Nevertheless, as Nathan Ballantyne (2023), from Arizona State University, outlined, researchers have posed many diverse, and arguably conflicting, definitions of intellectual humility. Specifically, Ballantyne divided these definitions into four clusters: attitude management, realistic self-assessment, low self-concern, and mixed accounts.

Attitude management

According to some researchers and scholars, individuals who are intellectually humble are more willing to modify their attitudes in response to additional evidence—and are thus not as defensive when their perspectives on various topics, such as abortion or conservation, are challenged. To illustrate,

- Hoyle et al. (2016) defined intellectual humility as a trait that affects the extent to which individuals are typically willing to reconsider and to modify their opinions,

- Van Tongeren et al. (2014) proposed that intellectual humility can be observed when people do not respond defensively to information that challenges their beliefs,

- Davis and Hook (2014) suggested that people who are intellectually humble can moderate their need to seem right about their beliefs or ideas.

These definitions vary, however, as to whether they regard intellectual humility as a trait, motive, or capability.

Realistic self-assessment

Other researchers and scholars define people as intellectually humble if they can accurately evaluate their beliefs or attitudes—or at least accurately evaluate the degree to which they can appraise their beliefs or attitudes effectively. That is, if people are intellectually humble, they may recognise their opinions could be biased or misguided. For example

- Gregg and Mahadevan (2014) define intellectual humility as individuals who can realistically evaluate their capacity to understand and to utilise knowledge,

- Church and Barrett (2016) propose that intellectual humility is the capacity of individuals to accurately monitor the validity of their beliefs.

Low self-concern

Some researchers and scholars instead define intellectual humility as a mindset or trait in which individuals are not unduly concerned with the significance, status, or superiority of their intellectual beliefs, attitudes, or capabilities. For instance

- according to Schellenberg (2015), when people experience intellectual humility, they are not too concerned about the importance, prestige, or glory of their intellectual perspectives or capacities—and thus can pursue their intellectual goals, such as develop knowledge, unhindered by these concerns,

- according to Roberts and Cleveland (2016), intellectual humility is the absence of intellectual pride—in which individuals are not preoccupied with the importance, status, power, or superiority of their intellectual knowledge, beliefs, or pursuits.

Mixed accounts

Finally, other researchers and scholars, when defining intellectual humility, refer to two or more of these clusters (e.g., Hopkin et al., 2014). Yet, even within each of these four clusters, the definitions vary appreciably (Ballantyne, 2023). To illustrate, scholars have not reached consensus on

- whether intellectual humility is a mindset that individuals may activate at various times, a capability that individuals have acquired, a personality trait or tendency, a suite of attitudes or values, or something else,

- whether researchers should assess the intellectual humility of people in general, the intellectual humility of people in specific domains, such as politics, or the intellectual humility of people on specific beliefs (cf., Hoyle et al., 2016),

- whether the tendency to consider the needs of other people, such as debate respectfully, is central to intellectual humility or merely a possible consequence of intellectual humility, as Ballantyne (2023) argues.

Implications and causes of this diversity

Because of this diversity in definitions, the causes and consequences of one characterisation of intellectual humility may diverge from the causes and consequences of other characterisations of intellectual humility. This divergence may prevent a lucid understanding of intellectual humility.

According to Ballantyne (2023), one possible source of this diversity emanates from how researchers derive these definitions. For example, some researchers merely adapt definitions of general humility and then confine these definitions to the intellectual domain. These researchers, therefore, assume that intellectual humility is a subset of general humility. Other researchers, however, regard intellectual humility as comprising features that general humility does not encompass. To reconcile these perspectives, Ballantyne (2023) argues that scholars should first delineate the core or mandatory features of intellectual humility. He argues that intellectual humility could represent the degree to which people can moderate personal motives—such as their motivation to perceive themselves as superior—to prioritise the need to process information that aligns with reality.

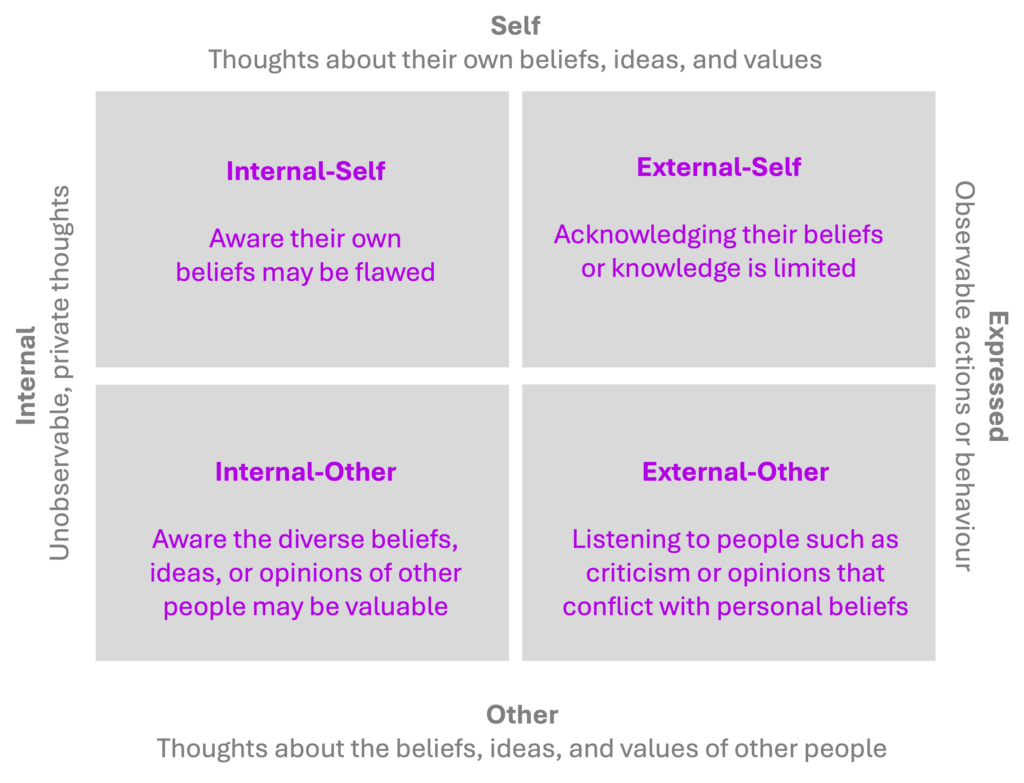

A 2 x 2 matrix

Porter, Baldwin, et al. (2022) designed a matrix that delineates four cardinal features of intellectual humility. In this matrix, presented in the following figure,

- the top two boxes represent the self—that is, the thoughts of individuals towards their own knowledge, beliefs, ideas, and values,

- the bottom two boxes represent the other—that is, the thoughts of individuals towards the knowledge, beliefs, ideas, and values of other people,

- the left two boxes represent internal experiences—that is, unobservable and private thoughts,

- the right two boxes represent expressed behaviour—that is, observable actions.

These two dimensions generate four boxes, each of which delineate one key feature of intellectual humility. In particular

- the internal-self corresponds to the tendency of some individuals to be aware their knowledge is limited and their beliefs may be flawed,

- the internal-other corresponds to the tendency of some individuals to be aware that beliefs, ideas, or opinions that other people express can be valuable,

- the external-self corresponds to the tendency of some individuals to acknowledge, aloud, that perhaps their knowledge is limited or their beliefs may be flawed,

- the external-other corresponds to the tendency of some individuals to respect the beliefs, ideas, or opinions of other people—even divergent opinions that may be unpleasant, such as criticisms.

Intellectual humility versus tolerance

At first glance, intellectual humility might seem to overlap with tolerance. For example, if people demonstrate intellectual humility, they recognise their beliefs may be flawed. Consequently, these individuals respect and consider diverse perspectives—even perspectives that diverge from their beliefs or preferences. Similarly, if people demonstrate tolerance, they are willing to accept beliefs with which they disagree or actions of which they disapprove.

The motivations of intellectual humility and tolerance, however, diverge markedly and fundamentally. According to Welch (2021), intellectual humility is an intellectual virtue—a virtue that enables people to gradually develop accurate knowledge and beliefs. That is, when people embrace intellectual humility and recognise their assumptions may be flawed, they become more likely to adopt beliefs that truly correspond to the world. In contrast, tolerance is a civic virtue. That is, when people display tolerance, they recognise that everyone should be granted the right to express their opinions in society. Tolerance thus facilitates equality and autonomy: features of society that many individuals value.

However, as Welch (2021) underscores, tolerance is not necessarily an intellectual virtue and may even impede intellectual humility. To illustrate, to demonstrate tolerance, individuals may strive to accept all beliefs or practices, even beliefs or practices that might seem outlandish at first glance, such as the notion the Earth is flat. Implicit in this approach is the assumption that beliefs cannot be classified as true or false. However, if beliefs cannot be classified as true or false—as correct or incorrect—individuals cannot appreciate that perhaps their assumptions may be flawed: a hallmark of intellectual humility. Tolerance may thus be incompatible with intellectual humility.

To recognise these virtues, Welch (2021) argues that intellectual humility and tolerance should be applied in separate circumstances or spheres. Intellectual humility is a virtue in circumstances in which truth, knowledge, and wisdom are prioritised. Tolerance is a virtue when civil participation, justice, and autonomy are vital.

Intellectual humility versus moral rationalisation

At first glance, intellectual humility may seem to overlap with the notion of moral rationalisation. Moral rationalisation is the inclination of some people to perceive rationality as a moral virtue (Ståhl et al., 2016). To illustrate, people who endorse statements like “It is a moral imperative that people can justify their beliefs using rational arguments and evidence” are assumed to demonstrate this inclination to perceive rationality as moral (Ståhl et al., 2016). They feel contempt towards irrational arguments. To illustrate the similarity between intellectual humility and moral rationalisation,

- if people exhibit intellectual humility, they recognise that some of their beliefs may be irrational and should thus be revised

- if people perceive rationality as moral, they also recognise that beliefs may be irrational and should be revised.

Nevertheless, intellectual humility and moral rationalisation also diverge. To demonstrate

- when people exhibit intellectual humility, they appear to direct their scepticism towards their own beliefs, perhaps inspired by the motivation to learn,

- when people exhibit moral rationalisation, they appear to deride the irrational beliefs of other people, inspired by the motivation to boost their status.

Marie and Petersen (2025) demonstrated this distinction empirically. Specifically, as these researchers demonstrated, when participants report elevated levels of intellectual humility and are thus more inspired to learn than to boost their status, they express a reluctance to share news reports that are derogatory towards their political rivals. In contrast, when participants tend to perceive rationality as moral and are thus inspired to boost their status, they are especially willing to share news reports that are derogatory towards their political rivals.

Collective intellectual humility

Introduction

According to Krumrei-Mancuso et al. (2024), researchers often measure and discuss the intellectual humility of individuals but seldom the intellectual humility of collectives—such as workgroups, juries, biologists, or indeed any community that shares a distinct goal and identity. Yet, because collectives, such as teams, often reach decisions and shape practices, attempts to measure the intellectual humility of collectives may be useful.

The intellectual humility of collectives is not merely the sum or aggregate of the intellectual humility of members. To illustrate, members of a workgroup may be attuned to the limitations in the knowledge or beliefs of this team—even if they are oblivious to their own limitations. Some practices or characteristics of the workgroup or collective may foster this awareness of collective limitations. Specifically, buoyed by the goal to seek truth and knowledge (Whitcomb et al., 2017), collectives are unlikely to develop intellectual humility unless two conditions are fulfilled:

- the members interact constructively to recognise and to address limitations in the knowledge and beliefs of one another and the collective,

- the members embrace norms, policies, and incentives to promote these constructive interactions—such as practices that encourage individuals to express dissent.

If these conditions are fulfilled, collectives that develop intellectual humility will tend to exhibit specific qualities. For example

- members will be more receptive to feedback—from both within and outside the collective,

- members will tend to deliberate carefully on complicated matters rather than reach expedient decisions,

- members will not overestimate the accuracy of their convictions,

- members will consider and integrate diverse knowledge and perspectives.

This intellectual humility of collectives may differ from the intellectual humility of individuals on several attributes. To illustrate

- collectives may exhibit greater intellectual humility than do individuals, partly because members sometimes recognise the biases and misconceptions of other people but not themselves (Pronin et al., 2002)

- collectives may sometimes impede or limit intellectual humility if the individuals strive to seek consensus and thus stifle diverging opinions (Raafat et al., 2009), although one persuasive, forceful dissident may be able to offset this problem (Stewart & Stasser, 1998),

Practical suggestions

Leaders can implement a range of practices to foster this collective intellectual humility. Here are some examples that Krumrei-Mancuso et al. (2024) propose

- to inspire members to contemplate the limitations of their beliefs or expectations, teams can imagine that a forthcoming a plan has failed and then predict the causes of this failure, called a premortem (Gallop et al., 2016),

- to inspire members to acknowledge the limitations of their beliefs, individuals should feel accountable and be evaluated on the accuracy and validity of the information or suggestions they present,

- to guide decisions, leaders can organise anonymous ballots, perhaps over several rounds, similar to a Delphi method (Beretta, 1996), to protect dissenters.

Krumrei-Mancuso et al. (2024) also suggest two approaches that researchers could adopt to measure collective intellectual humility. Specifically, researchers could

- invite each individual in a collective to indicate the extent to which they recognise the limitations in the knowledge and beliefs of members as well as feel committed to foster an environment that encourages intellectual humility,

- assess the degree to which collectives have developed the culture or apply the practices that foster this intellectual humility.

Leadership humility

Introduction

Inspired by the work of Bradley Owens, many studies have explored whether humility in leaders benefits organisations (e.g., Owens & Hekman, 2016). Arguably, the hallmarks of this humility in leaders might diverge from the hallmarks of humility in people generally. For instance, after inviting managers to define leader humility, Owens and Hekman (2012) suggested this attribute comprises three main features:

- admitting mistakes and limitations,

- modelling teachability, and

- spotlighting follower strengths and contributions.

Leadership humility: A study in Singapore

Likewise, to explore the hallmarks of humility in Singaporean leaders, Oc et al. (2015) conducted two studies. First, the researchers interviewed 25 Singaporean residents who were MBA students, PhD students in general management, or other employees, most of whom were supervisors or managers. The questions invited participants to discuss the definition of leader humility and the behaviours that epitomise this humility. An inductive analysis of the responses uncovered nine features of leader humility (Oc et al., 2015), the first three of which were mentioned the most often:

- modelling their receptivity to correcting their behaviour and their teachability

- empathy and approachability

- showing modesty

- an accurate view of self

- recognising the strengths and achievements of followers

- leading by example

- working together for the collective good,

- showing mutual respect and fairness

- mentoring and coaching.

In their second study, 307 Singaporean supervisors completed a survey, in which they were invited to define leader humility and the behaviours that exemplify this humility. The researchers then sorted the responses into the nine features, as uncovered in the previous study, as well as identified responses that do not align to these features. Each of these nine features was mentioned by at least 29 of the participants, validating the first study (Oc et al., 2015).

Four of these features— an accurate view of self, recognising the strengths and achievements of followers, showing mutual respect and fairness, and modelling their receptivity to correcting their behaviour and their teachability—were analogous to four of the hallmarks of general humility, as defined by Tangney (2000). The other features, however, such as working together for the collective good, mentoring and coaching, as well as empathy and approachability, appeared to be specific to leader humility.

Existential humility

Overview

According to Green et al. (2023), some people demonstrate existential arrogance—or the tendency to believe their life can significantly shape, and even improve, the world enduringly and monumentally. To maintain this perspective, these individuals depend on significant beliefs, such as the belief in their intelligence, to spark their motivation. If they revised their beliefs, key facets of their identity would dissolve. Consequently, individuals who display existential arrogance are often unwilling to revise their beliefs in response to evidence, manifesting as intellectual arrogance.

The converse of this perspective is existential humility: the capacity or tendency of individuals to recognise, and to accept, that human life is both transitory and limited in impact. In contrast to their existentially arrogant counterparts, people who demonstrate existential humility may be more willing to update their beliefs over time, revealing an overlap between existential humility and intellectual humility.

Indeed, as Green et al. (2023) argue, to gauge intellectual humility, researchers should assess this attribute in response to existential threats. That is, people can readily display and experience intellectual humility in settings or circumstances that foster this humility—such as workplaces in which peers are willing to question their beliefs. In contrast, people cannot as readily maintain this intellectual humility when conviction or certainty in their beliefs is reinforced or adaptive.

The authors invoked terror management theory to propose that intellectual humility should be tested in response to existential threats. Specifically, according to terror management theory (Greenberg et al., 1990), because of several immutable properties of the university, human lives are, from one perspective, futile and meaningless. Death is the only certainty in a world that humans cannot readily shape or control but need to reach decisions and navigate regardless. When individuals recognise the futility of their lives, they experience a profoundly unpleasant state, called existential threat. If humans had not evolved to experience this sensation, they would not have felt as compelled to preserve their life, eradicating the species over time.

To circumvent this existential threat, individuals develop an understanding of how the world operates and the role of humans in this world. For example, they may believe that some entity, such as a collective or ideology, will persist indefinitely. To belong to this entity, they learn the norms they must observe, such as the rituals they must practice. Accordingly, they feel their contributions or role will be recognised and preserved indefinitely, after they die, called symbolic immortality.

Because these beliefs about the world temper existential anxiety, individuals furiously defend threats to these perspectives, such as arguments that contradict their opinions about religion (Greenberg et al., 1990; Solomon et al., 2004). In response to reminders of their death, for example, individuals fiercely defend their nation (Nelson et al., 1997) or the other collectives to which they belong (Harmon-Jones et al., 1996). Accordingly, individuals are especially inclined to defend beliefs that temper their existential anxieties—beliefs that confer a sense of immortality. Consequently, people who recognise the limitations of these existential beliefs and gradually update these beliefs over time display profound intellectual humility. These individuals are especially likely to be tolerant of diverse religions, ideologies, and perspectives. such as their motivation to perceive themselves as superior—to prioritise the need to process information that aligns with reality.

Philosophical discussions of humility: The work of Jeanine Grenberg

Overview

In her seminal book, “Kant and the ethics of humility: A story of dependence, corruption, and virtue”, Jeanine Grenberg positioned humility as the foundation of all virtues. Her definition of humility is predicated on an understanding of dependence and corruption. According to Grenberg,

- humans are greatly dependent on other people; that is, their relationships and circumstances profoundly shape and limit their lives as well as guide their moral decisions—decisions about which actions are right and wrong,

- yet, individuals prioritise their personal needs over the moral principles of their society—a universal moral corruption that emanates from rational consideration rather than inherent evil.

Humility emanates from an awareness of dependence and corruption. That is

- humility evolves as people acknowledge they are both profoundly dependent on other people but also inclined to prioritise their personal needs over the goals of their community,

- humble people recognise they are moral agents, granted the autonomy to constrain the degree to which they prioritise these personal interests,

- these individuals can thus align their needs with a respect towards the moral principles or laws that benefit society, forging moral progress,

- in this sense, humility revolves around how humans position themselves relative to moral principles or laws—and not, necessarily, how they position themselves relative to other people.

According to Grenberg, humility and self-respect complement one another. To illustrate, if individuals respect themselves and appreciate their worth, but do not experience humility, they are susceptible to pride and arrogance. Consequently

- these individuals do not fulfill moral principles or establish reciprocal, trusting relationships with the people on whom they are dependent,

- devoid of these relationships, these individuals are thus unable to achieve their goals.

Yet, if individuals experience humility and thus appreciate their dependence and corruption, but do not respect themselves, they may become servile. That is, they relinquish their needs to accommodate other people, culminating in despair. In contrast, if individuals experience humility and respect themselves,

- they naturally balance their personal needs with moral principles,

- they reconcile their dependence with their dignity, preventing both arrogance and despair,

- they are aware of both their limitations and strengths, manifesting as a balance between confidence and modesty.

Grenberg positions her book as a fundamental reinterpretation of the moral philosophy that Immanuel Kant promulgated. Traditionally, scholars often regarded the moral philosophy of Kant as devoid of warmth, embedded in the assumption that moral acts are rational duties rather than virtuous behaviours. According to Grenberg, the moral philosophy that Kant expounded can be understood as an ethics in which humility is a fundamental virtue. Specifically, Kant conceptualised humans as both frail—that is, dependent and corrupt—but also worthy—that is, dignified and able to regulate their behaviour.

Intellectual humility versus intellectual servility

Many studies have uncovered the benefits of intellectual humility—the tendency of individuals to acknowledge limitations in their knowledge or uncertainty in their beliefs as well as to embrace diverse perspectives. Nevertheless, researchers have raised the concern that some people may orient their attention unduly to their limitations, even to the degree they overlook their strengths, compromising their learning, confidence, motivation, and other goals. This possibility, however, does not indicate that intellectual humility should be moderated. Instead, this possibility implies that researchers may need to differentiate two overlapping but distinct attributes: intellectual humility and intellectual servility. As Mcelroy-Heltzel et al. (2023) suggest, although both attributes correspond to an awareness of limitations in knowledge and beliefs

- in people who experience intellectual humility, this awareness of limitations tends to emanate from a motivation to learn and to extend knowledge,

- in people who experience intellectual servility, this awareness of limitations may emanate from limitations in self-esteem or confidence,

- people who experience intellectual humility are thus more attuned to their intellectual strengths than are people who experience intellectual servility.

Accordingly, unlike intellectual humility, intellectual servility may coincide with a range of undesirable attributes or behaviour. To illustrate, Mcelroy-Heltzel et al. (2023) conducted a study of 94 undergraduate students, representing diverse races, who completed a questionnaire that included the following scales:

- a measure of intellectual servility, such as “‘I defer to others so they will like me (about an issue I care deeply about)” (McElroy-Heltzel et al., 2021),

- the Specific Intellectual Humility Scale,

- the Big Five Inventory (John et al., 1991) to assess conscientiousness, openness to experience, agreeableness, extraversion, and neuroticism,

- the Almost Perfect Scale-Revised (Slaney et al., 2001) to gauge adaptive perfectionism, defined as high standards, and maladaptive perfectionism, defined as people who never feel satisfied with their performance, such as “Doing my best never seems to be enough”,

- a measure of civic engagement, such as the frequency with which they “attended a political rally or speech” (Smith, 2013).

As the findings revealed, intellectual servility, although positively associated with intellectual humility, was inversely associated with conscientiousness, openness to experience, and civic engagement but positively associated with maladaptive perfectionism: a tendency that disrupts academic performance (Madigan, 2019). Thus, intellectual servility shares features with intellectual humility, such as an awareness of personal limitations, but is underpinned by limited confidence and not the inspiration to learn.

Appreciative humility versus self-abasing humility

This distinction between humility and servility overlaps with a similar distinction, proposed and validated by Weidman et al. (2018), between appreciative humility and self-abasing humility. In essence

- appreciative humility primarily revolves around respect towards other people—and tends to emanate from personal success,

- in contrast, self-abasing humility primarily revolves around shame and the tendency to be submissive—and tends to emanate from personal failure,

- at least superficially, self-abasing humility may coincide more with servility instead of the more prevailing definitions of humility.

In the first study, one set of participants were invited to list words or phrases that reflect thoughts, feelings, or actions they associate with humility. This procedure unearthed 26 words that are related to humility, such as modest, unpretentious, embarrassed, and quiet. Then

- another set of participants received pairs of words that relate to humility, such as modest and unpretentious

- for each pair, participants indicated the extent to which these two words are similar to each other,

- these ratings were subjected to hierarchical cluster analysis.

The cluster analysis uncovered two distinct sets of words. The first set comprised words that relate to appreciate humility, such as respectful, kind, compassionate, understanding and modest. The second set comprised words that relate to self-abasing humility, such as embarrassed, meek, quiet, self-conscious, and shy (Weidman et al., 2018).

In their second study, University students, enrolled at the University of British Columbia, were invited to recall and describe a time when they felt or experienced humility. Next, participants indicated the degree to which they

- demonstrate 54 words that are related to humility, such as unpretentious or embarrassed

- felt happy, content, pleased, or unhappy after this event, called evaluative valence.

Then, another sample of individuals rated the degree to which these experiences seemed desirable. Finally, four research assistants rated the degree to which each experience seemed to be a success or a failure. Overall, the results also confirm that humility can be divided into two kinds: appreciative and self-abased. For example,

- after individuals rated themselves on 54 words that are related to humility, a factor analysis uncovered two distinct factors that correspond to appreciative and self-abased humility,

- an overarching factor was positively associated with appreciative humility and inversely associated with self-abased humility,

- these findings were observed even after controlling evaluative valence and social desirability.

- appreciative humility tended to be associated with events that were deemed as successes, and self-abased humility tended to be associated with events that were deemed as failures (Weidman et al., 2018).

The third study explored how these two facets of humility, appreciative and self-abased, are related to other traits. For example, as this study revealed, appreciative humility was positively associated with extraversion, openness, conscientiousness, agreeableness, self-esteem, agency, and communion but negatively associated with neuroticism and submissiveness. Self-based humility generated the opposite pattern of relationships. As a fourth study revealed, even when experts on this topic were invited to list words that are related to humility, the words they generated can be divided into two clusters: appreciative and self-abasing (Weidman et al., 2018).rvility shares features with intellectual humility, such as an awareness of personal limitations, but is underpinned by limited confidence and not the inspiration to learn.

Philosophical discussions of humility: Ideal-contractualist ethical theories

Ideal-contractualist ethical theories

In an influential paper, Green (1973) proposes that humility is the fundamental virtue that enables people to reach ethical and just decisions. This argument, embedded within a broader discussion about Jewish ethics, invokes the ideal-contractualist ethical theory that John Rawls (1971, 1999) proposed, to inform this argument.

According to Rawls, to decide which rules, principles, or policies are fair and just, people should not merely depend on intuition, tradition, or authority. Instead, individuals should choose fair and just rules behind what Rawls calls a veil of ignorance. To illustrate

- people should imagine they are members of a panel who must decide which rules should govern a new society, called parties to the original position

- however, none of the members know their life circumstances in this forthcoming society, such as their gender, ethnicity, capabilities, income, education, or health,

- because they do not know how their life will unfold—such as whether they will be wealthy or impoverished—people will choose rules, principles, or policies that are fair to everyone rather than biased towards particular segments of the population.

If individuals contemplate this hypothetical scenario, their choices will tend to conform to two principles. First, they will tend to choose rules that guarantee the same basic liberties to everyone, such as freedom of speech or the right to participate in politics. Second, they may permit some inequality, but only if this inequality benefits the least advantaged members of society, called the difference principle.

To illustrate the veil of ignorance, consider a panel of individuals who need to choose rules around criminal justice. These individuals would not know whether they may be members of a vulnerable community, in which people may be accused erroneously, or living in a dangerous neighbourhood. Accordingly, these individuals would most likely choose rules that

- diminish the risk of wrongful punishment,

- decrease the likelihood that people who perpetrate crime will repeat these offences,

- yet protect the civil liberties of criminals.

Role of humility

However, as Green (1973) underscores, to embrace this veil of ignorance, individuals need to be able to envisage themselves in diverse circumstances. Arguably, only people who are sufficiently humble can achieve this goal. To demonstrate, Tangney (2000) delineates some of the key features of humility, such as

- perspective, in which humble people recognise they are merely one person in an enormous, interconnected world and thus do not inflate their significance to society,

- openness, in which humble people are receptive to ideas or information that contradicts their assumptions or preferences.

- limited self-focus, in which humble people consider the needs and perspectives of other individuals and the universe more broadly,

All these features of humility enhance the capacity of individuals to embrace the veil of ignorance. For example,

- because of perspective and openness, individuals recognise the rules they prefer now may not be fair or appropriate to other people

- indeed, because of limited self-focus, individuals can imagine the perspective of diverse communities and thus propose rules that benefit these communities.

As this argument implies, humility could be regarded as the capacity to appreciate the perspectives of diverse communities and accommodate these perspectives.

Historical and religious conceptualisations of humility

Greek philosophy

As Peterson and Seligman (2004) outlined in their influential book, entitled “Character strengths and virtues”, Greek Stoic philosophers regarded humility as a virtue—as a feature of excellence. Indeed, during this time, philosophers did not often refer to humility, primarily because the significance of this virtue was so broadly accepted. Educated individuals, in this period, were informed of the shared limitations of themselves and all humans. So, humility was prevalent and assumed.

Taoism

In contrast, proponents of Taoism often alluded to the significance of humility (see Morris et al., 2005; Wicks, 2019). In Taoism, the three cardinal virtues are humility, compassion, and frugality. Humility is regarded not as a frailty but as a source of peace, and thus power, that emanates from surrendering the need to dominate other people. That is, rather than strive to dominate, humble individuals recognise the power that infuses the universe and emanates from their connection with Tao—the ineffable, primordial force that governs existence. To appreciate humility, in the Tao Te Ching, the central text of Taoism, humility is often equated to

- water—flowing to the lowest spaces, adapting to the container, and benefiting all life, without ego or need to be recognised,

- an empty vessel, with no preconceived notions but instead open to all experiences.

Several practices may epitomise this humility. That is, to nurture their humility, individuals can

- listen quietly, overriding the need to speak constantly, embracing the wisdom that often emanates from the quiet,

- refrain from comparing themselves with other individuals and competing too often,

- living a simple, natural life, devoid of too many needs and desires,

- refrain from the need to seek praise or personal gain from acting virtuously.

Judaism

Humility is also central to the monotheistic traditions of Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. For example, Nelson (1985) delineated the central role of humility in Judaism. Nelson acknowledged that Judaism, like most religious traditions, should not be regarded as a single, unified, and homogenous philosophy—but a collection of biblical, Rabbinical, and philosophical perspectives. Nevertheless, Nelson argues that many of these Jewish perspectives converge towards similar arguments around humility. For example, Judaism tends to embrace two distinct but overlapping variants of humility:

- humility as the respect, understanding, and forgiveness that people should direct to all social relationships, and

- humility as obedience or loyalty to God and the principles that God espouses

Humility is perceived as an antidote to the most corrupting influence on humans: pride. Pride is regarded as

- a rebellion against God, in which individuals prioritise their personal interests over divine wishes,

- equivalent to the worship of idols,

- a denial of the essential principles of religion and society.

Cautions against pride tend to pervade many biblical and Rabbinical texts. For example

- Proverbs Chapter 16 warns that “Everyone who is arrogant is an abomination to the Lord”

- the unfortunate fates of many characters in the bible, such as the individuals who constructed the Tower of Babel and Ahitophel, a man of wisdom, but no humility, who eventually hanged himself.

Islam

Islam, although also diverse, tends to espouse similar attitudes towards humility. Muslims are implored to regard God as Kabir, equivalent to “The Great”, and to surrender entirely to the capabilities and omnipotence of God. Indeed, word Islam is derived from the Arabic word aslama—a term that means to surrender or submit to God. The term Muslim refers to a humble person who submits to God (see Mir, 2010).