The association between demographics and narcissism

Narcissism across gender and relationship status

To assess whether gender and other demographics affect the incidence of narcissistic personality disorder, Stinson et al. (2008) distilled insights from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions, Wave 2—a huge dataset on the mental health disorders and demographics of individuals in the United States. Specifically, to generate this dataset, a representative sample of 34 653 individuals were interviewed. For example, to diagnose narcissistic personality disorder, individuals received a series of questions about how they feel or act in typical situations. The researchers then applied the DSM-IV criteria to diagnose narcissistic personality disorder as well as other personality disorders. As the data revealed

- 7.7% of men and 4.8% of women were diagnosed with narcissistic personality disorder,

- this incidence was 5% in people who were married or cohabiting with a partner, 7.3% in people who had separated from a partner or widowed, and 9.5% in people who had never been married (Stintson et al., 2008).

Narcissism across age

Narcissism does tend to diminish as individuals age—as a meta-analysis, published by Orth et al. (2024) in Psychological Bulletin, confirmed. Specifically, to conduct this meta-analysis, the researchers extracted data from 51 samples. These samples comprised over 37 000 participants in aggregate. The analysed examined three key facets of narcissism: agentic narcissism, antagonistic narcissism, and neurotic narcissism. All three facets diminished with age, although this decrease was large for neurotic narcissism and relatively small for agentic narcissism.

The researchers proposed a range of reasons to explain this decrease in narcissism over time. First, according to the social investment model of personality development, as Roberts et al. (2008) proposed, when individuals age, they gradually cultivate traits that are useful to the roles they assume. Typically, levels of agreeableness, emotional stability, and conscientiousness increase, because these traits are adaptive in many relevant circumstances. Narcissism—an inclination that tends to coincide with limited agreeableness, for example—should thus dissipate.

Second, according to the socioemotional selectivity theory—first proposed by Carstensen et al. (1999) but validated across many studies (for a review, see Carstensen & Mikels, 2005 and Moss & Wilson, 2017)—as people approach a transition, such as death, they prioritise close, personal relationships and emotional stability over the acquisition of knowledge, resources, and status. Narcissism, emanating from a pursuit of immediate status, should thus subside.

Third, according to the reality principle model, proposed by Foster et al. (2003), younger individuals, such as adolescents, are more likely to experience failures, rejections, and similar problems as they experience unfamiliar settings. This accrual of failures may diminish narcissism, as individuals become attuned to their limitations.

Narcissism across generations: Increases over time

As Orth et al. (2024) revealed, this pattern in which narcissism diminishes as individuals age is observed in all generations. Yet, narcissism also varies across the generations, consistent with generational cohort theory (e.g., Sessa et al., 2007).

To illustrate, in 2008, Twenge et al. undertook a technique called cross-temporal meta-analysis. In particular, these researchers examined scientific studies that have examined narcissism since the 1980s. These studies generally reported the average values of narcissism for various age groups. These figures were then subjected to statistical analyses to ascertain whether average levels of narcissism changed over time in specific age groups, usually undergraduate students.

This analysis revealed that narcissism has indeed increased over time in specific age groups. To illustrate, the average college student in 2006 generated a higher level of narcissism than 65% of college students in the 1980s. They were more likely to endorse items like “I think I am a special person” and “I can live my life any way I want to” (for a review, see Twenge & Campbell, 2008).

Several accounts may explain this increase in narcissism across generations, at least from the 1980s to the 2000s. For example, according to Twenge et al. (2010), many of the changes across generations might reflect a shift in the goals of individuals. That is, in the 1950s and 1960s, the priorities and activities of organisations did not shift rapidly. Therefore, individuals often worked at the same organisation, in a similar role, over many years. They maintained their relationships with colleagues, friends, and communities. Generations reared during these times, hence, often pursued goals that coincide with their underlying values, such as close relationships with friends and communities, called intrinsic goals.

In later decades, the priorities and activities of organisations often shifted rapidly and unexpectedly. Individuals would often need to shift their roles and compete to secure jobs. During this time, to compete successfully, they needed to boost their status. To achieve this objective, people needed to impress other people, called extrinsic goals, often manifesting as materialism. This pursuit of immediate status tends to amplify narcissism

Indeed, evidence indicate that younger generations in the 2000s were not as motivated to pursue intrinsic goals than younger generations in previous decades. Involvement in community groups had dissipated since the 1960s (Putnam, 2000). Interest in government activities had waned. Intimacy in friendships had also diminished; fewer people at this time felt they could readily confide in their closest friends (McPherson et al., 2006).

Narcissism across generations: Alternative perspectives

Some research has challenged the notion that narcissism has tended to escalate over recent decades—as measured by the Narcissistic Personality Inventory. For example, as Wetzel et al. (2017) suggest, interpretations of the items may vary across the decades. Several properties of the data are indicative of this possibility, such as

- changes in the number of subscales or factors of the Narcissistic Personality Inventory over the years,

- changes in item loadings—that is, relationships between each item and the corresponding factor—over the years,

- changes in the mean of each item, even after controlling the overall score.

Wetzel et al. (2017) did indeed uncover some evidence of these changes in the mean of some item, even after controlling the overall score. This finding implies that interpretations of this inventory may have shifted over time. The meaning of some item might have evolved.

Wetzel et al. (2017) also utilised a range of techniques, such as the partial-invariance model (see Robitzsch & Lüdtke, 2020), to control or to override the impact of this change over time. After this change was controlled, some facets of narcissism, such as vanity, entitlement, and need to be a leader, diminished from 1990 to 2019, contrary to previous observations.

Finally, Wetzel et al. (2017) suggested that changes in demographics across the generations—such as the proportion of participants who are Asian American or African American—could also have affected the observed shifts in narcissism over time. To illustrate, across the decades, vanity increased in Asian American students but decreased in other American students. Analyses that do not control race or ethnicity, therefore, may be biased.

The association between genes and narcissism

To assess the extent to which narcissism can be ascribed to genes, research has examined whether levels of narcissism are more similar in identical or monozygotic twins compared to fraternal or dizygotic twins (for a review, see Luo & Cai, 2018). That is, monozygotic twins share all their genes, whereas dizygotic twins share only half their genes, but are otherwise reared in a similar family environment. Accordingly,

- if a trait, such as narcissism, is significantly more similar in monozygotic twins compared to dizygotic twins, this trait can partly be ascribed to inherited genes,

- if a trait is more similar in twins who were reared in the same environment compared to individuals who were not reared in the same environment—after controlling genes—this trait can partly be ascribed to this shared environment.

A range of studies has explored whether narcissism can be ascribed to genes, a shared environment, or other circumstances (Cai et al., 2012; Cai et al., 2015; Kendler et al., 2008; Livesley et al., 1998; Luo, Cai, & Sedikides, 2014; Luo, Cai, Sedikides, & Song, 2014; Torgersen et al., 2000; Vernon et al., 2008). Some of these studies have explored the extent to which narcissistic personality disorder can be ascribed to genes or a shared environment. For example

- in a sample of 686 Canadian pairs of twins, 44% of the variation in narcissistic personality disorder—as gauged by a subscale of the Dimensional Assessment of Personality Disorder-Basic Questionnaire (Livesley & Jackson, 1990)—was ascribed to genes, 0% to a shared environment, and 56% to other circumstances (Livesley et al., 1998),

- in a sample of 221 Norwegian pairs of twins, in which one twin had been diagnosed with a mental disorder, 77% of the variance in narcissistic personality disorder was ascribed to genes and 23% to other circumstances (Torgersen et al., 2000),

- in a sample of 2794 Norwegian pairs of twins, 37% of the variation in narcissistic personality disorder—as measured by the Structured Interview for DSM-IV—was imputed to genes and the remainder to other circumstances (Kendler et al., 2008).

Other studies, in contrast, have examined the degree to which measures of various narcissistic traits, such as grandiose narcissism or communal narcissism, can be ascribed to genes or a shared environment. To illustrate

- in a study of 139 pairs of twins from the US and Canada, 59% of the variations in grandiose narcissism, as measured by the Narcissistic Personality Inventory, could be ascribed to genes, 0% to a shared environment, and 41% to other circumstances (Vernon et al., 2008),

- in a study of 304 pairs of twins from China, 47% of the variations in grandiose narcissism could be ascribed to genes and 53% to other circumstances (Luo, Cai, Sedikides, & Song, 2014),

- 37% of the variance in more adaptive facets of narcissism—such as authority and self-sufficiency—and 44% of the variance in less adaptive facets of narcissism—such as entitlement, exploitation, and exhibitionism, as defined by the Narcissistic Personality Inventory—were ascribed to genes; the studies also implied that adaptive narcissism and maladaptive narcissism could primarily be ascribed to different genes and environments, despite some overlap,

- 42% of the variance in communal narcissism, in which individuals tend to inflate their morality and kindness, could be ascribed to genes and 58% could be ascribed to other circumstances; the studies also revealed that grandiose narcissism and communal narcissism could primarily be ascribed to different genes and environments.

In short, as these findings reveal, more than a third, and probably at least half, the variance in narcissistic disorders and traits can be ascribed to genes. Distinct variants of narcissism can mainly, but not entirely, be ascribed to different genes. These variations in narcissism cannot be ascribed to shared environments—although several limitations of these methods challenge this conclusion. For example, the genes or temperament of children can shape the environment; hence, researchers cannot definitively separate the impact of genes and environments.

Limited mindfulness and narcissism

Features of mindfulness

Arguably, narcissism could emanate from limited levels of mindfulness. When people are mindful, they observe their immediate surroundings, thoughts, or feelings, effortlessly and naturally, but devoid of judgment, evaluation, or analysis. More precisely, Germer (2005) delineated three features of mindfulness:

- First, mindfulness coincides with an acute sense of awareness. The surroundings, thoughts, or feelings that individuals observe seem sharp and focussed rather than hazy and diffuse.

- Second, individuals direct this awareness to their immediate experience. That is, these individuals observe the sights and smells in their surroundings or the feelings, thoughts, and sensations they are experiencing now—instead of past memories or future possibilities.

- Third, individuals accept, rather than judge, evaluate, or elaborate, their feelings, thoughts, or sensations.

Mindfulness can be regarded as a state, trait, practice, or process. For example

- people may experience a state of mindfulness momentarily,

- alternatively, some people may experience this state more frequently or intensely, implying that mindfulness could be regarded as a trait (Brown & Ryan, 2003),

- or individuals may complete mental or physical exercises, such as various meditations, that are designed to elicit this state, suggesting that mindfulness may be a practice or intervention,

- finally, mindfulness could be conceptualised as a mental operation or process and not only as a passive state of mind.

Rationale

For several reasons, mindfulness could dampen narcissism. First, when people experience mindfulness, they do not yield to temptations, such as unhealthy food, as rapidly (Papies et al., 2012). For similar reasons, they may override the urge to inflate or to exaggerate their status, achievements, or capabilities—a defining feature of narcissism.

Second, when individuals experience mindfulness, they are not as inclined to shun unpleasant thoughts. For example, in contrast to other people, mindful individuals are more willing to contemplate their mortality rather than suppress thoughts about death (Niemiec et al., 2010). For similar reasons, when people experience mindfulness, they may be willing to contemplate their limitations and shortcomings—diverging from the typical behaviour of vulnerable narcissists.

Evidence: A systematic review

To explore this association between mindfulness and narcissism, Ganster et al. (2025) conducted a systematic review. To unearth relevant studies, the researchers entered the search terms narcis* and mindful* into PsycInfo, PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, and Google Scholar. This procedure uncovered 22 publications, comprising 26 distinct samples and 10 000 participants, that explored the relationship between narcissism and mindfulness. After a comprehensive analysis of these studies, Ganster et al. (2025) concluded that

- across the studies, mindfulness was negatively, but only modestly, associated with narcissism (r = – 0.10),

- however, this association diverged across the studies—perhaps because the magnitude, and may be even the direction, of this relationship may vary across facets of narcissism,

- specifically, this inverse association between mindfulness and narcissism may be more pronounced in vulnerable narcissism and antagonistic narcissism.

Evidence: Randomised control trials

Some randomised control trials have uncovered preliminary evidence to suggest that mindfulness may diminish narcissism rather than vice versa. For example, Sistani, et al. (2024) conducted an informative study that was published in the Journal of Adolescent and Youth Psychological Studies. The participants were single women, aged 35 or over, enrolled at universities in Isfahan, Iran, who had expressed a reluctance to marry. Fifteen of these women participated in eight sessions of mindfulness training protocol that Baer (2003) had recommended. For example

- participants were exposed to exercises such as body scan meditation, mindful breathing, and an exercise in which they imagine the sensations of eating a raisin,

- participants were encouraged to embrace mindfulness during their daily activities, such as brushing their teeth, sitting, and eating,

- participants learned about the myths of meditation, such as the notion that meditation is designed to foster relaxation,

- participants also learned skills they could apply to navigate challenging situations, such as conflict and stress.

Before and after participating in these sessions, participants completed a version of the Narcissistic Personality Inventory that comprises 16 items as well as a measure of perfectionism (Hill et al., 2004). Unlike a control group of participants who were not exposed to mindfulness, individuals who completed the mindfulness training exhibited a decrease in both narcissism and perfectionism (Sistani et al., 2024). According to the authors, these changes may also diminish a reluctance to marry.

Other studies also imply that mindfulness training may diminish narcissism. For example, in one study, conducted by Beig et al. (2023), 30 Iranian teenagers completed eight sessions of mindfulness training and compassion therapy. Before and after these sessions, the participants completed the Dark Triad personality scale (Jonason and Webster, 2010)—an instrument that gauges narcissism as well as psychopathy and Machiavellianism. In contrast to 15 teenagers who did not attend these eight sessions, the participants who completed mindfulness training and compassion therapy demonstrated a decrease in narcissism over time. Although encouraging,

- these findings do not clarify which activities or features of the sessions diminished narcissism,

- consequently, whether mindfulness or some other state reduces narcissism may warrant further research.

Impulsivity: A preference of small immediate rewards over larger delayed rewards

To boost their status, some individuals gradually develop their skills, refine their capabilities, achieve their goals, and contribute to society. In contrast, narcissistic individuals tend to flaunt, and often exaggerate, their skills, capabilities, achievements, and contributions. Accordingly, in general, narcissistic people can initially attract status or admiration but are often disliked or distrusted later. Narcissism, therefore, may emanate from the inclination of some people to prioritise immediate rewards over future rewards—sometimes called temporal discounting.

Measures of temporal discounting

Researchers have designed a range of measures to assess temporal discounting in individuals (e.g., Kirby & Marakovic, 1995, 1996). To illustrate, participants may be asked whether they would prefer $100 now or $150 in 6 months. Then, participants might be asked whether they would prefer $200 now or $250 in 1 year. After a series of similar questions, various formulas, models, or tools can be applied to estimate the extent to which the perceived value of rewards diminishes over time. Individuals who prefer small amounts now to large amounts in the future are deemed to discount or trivialise delayed rewards. Consequently, they gravitate to immediate rewards, often manifesting as impulsive behaviour.

One variant of this task is called the titration method (e.g., Bickel et al., 1999). Participants first indicate whether they prefer $1000 now to $1000 in one week. Almost all participants prefer $1000 now. The experimenter then changes the first amount to $990. That is, participants indicate whether they prefer $990 now to $1000 in one week. The experimenter then continues to reduce the first amount to $960, $920, $850, $800, $750, and so forth until the participant no longer prefers the immediate amount. The entire sequence is then repeated for 6 other delays: 2 weeks, 1 month, 6 months, 1 year, 5 years, and 25 years.

Researchers also tend to distinguish between exponential and hyperbolic discounting (see Ainslie, 2001, 2006). If discounting is exponential, the value of some reward diminishes proportionately with time. If $100 today is equivalent to $200 in one week, then $100 today is also equivalent to $300 in two weeks. If discounting is hyperbolic, the value initially does not diminish as steeply over time as does exponential discounting. After some particular time, the value then begins to diminish more steeply (for more advanced and accurate equations, such as the ITCH model, see Ericson et al., 2015).

A systematic review

Coleman et al. (2022) conducted a systematic review to explore the association between temporal discounting and narcissism. This review was published in Personality Disorders: Theory, Research, and Treatment. To unearth relevant publications, the researchers enter narciss* and various synonyms of temporal discounting—such as delay discounting, future discounting, delayed gratification, deferred gratification, and intertemporal choice—into three databases: PubMed, PsycINFO, and Web of Science. This search uncovered seven publications, comprising eight distinct studies, that have examined whether temporal discounting is more pronounced in people who exhibit narcissism. Four of these studies were deemed to be high in quality. To illustrate some of the key findings

- in a study of 194 university students, Buelow and Brunell (2014) showed that measures of grandiose narcissism and entitlement were positively associated with the level of temporal discounting, generating r values of .17 and .29 respectively,

- in a study of 299 people from the general public, Crysel et al. (2013) revealed a correlation of .17 between a measure of grandiose narcissism and temporal discounting—almost identical to the correlation that Jonason et al. (2020) also reported,

- in three distinct studies, Malesza and Kaczmarek (2018, 2021a, 2021b) uncovered correlations of .34 to .46 between measures of grandiose narcissism and temporal discounting,

- however, in one study (Malesza & Kaczmarek, 2016), this correlation was close to zero,

- finally, as Malesza and Kaczmarek (2018) showed, the correlation between vulnerable narcissism and temporal discounting approached zero.

Taken together, Coleman et al. (2022) concluded that temporal discounting—or the tendency to prefer small immediate rewards to larger delayed rewards—is pronounced in grandiose narcissists, although correlations tend to be small to moderate. Because of limited research, the association between vulnerable narcissism and temporal discounting has yet to be established definitively.

Determinants of temporal discounting: Episodic future thinking

Many other individual characteristics, workplace conditions, personal circumstances, or mental exercises may affect temporal discounting or impulsivity—and thus, in principle, may foster or diminish narcissism. To illustrate, one mental exercise that may decrease temporal discounting is called episodic future thinking

Specifically, in one study, published by Daniel et al. (2013), some participants, all of whom were overweight or obese, completed an exercise in which they

- imagined desirable events that might unfold in 1 day, 2 days, 1 week, 2 weeks, 1 month, 6 months, and 2 years,

- described each of these events; these descriptions were audio recorded.

In the control condition, participants merely described entries of a travel blog, written by someone else. Next, participants completed a temporal discounting task. They were asked whether they would prefer, for example, $10 now or $100 in 1 day, 2 days, 1 week, 2 weeks, 1 month, 6 months, and 2 years. While completing this task, their previous description associated with this time period was replayed, and participants were asked to imagine this event. Finally, the participants were granted access to unlimited unhealthy food.

If participants imagined hypothetical future events, temporal discounting decreased. That is, participants were more likely to choose a higher reward in the future than a modest reward now. These individuals were also more likely to refrain from eating the unhealthy food.

Determinants of temporal discounting: Cues and events in the environment

Physical features in the surrounding environment can also elicit temporal discounting and potentially promote narcissism. In one study that Zhong and DeVoe (2010) published in Psychological Science, some participants were exposed to subliminal pictures of fast-food logos, such as KFC, Taco Bell, and Burger King. Exposure to these logos was shown to expedite the rate at which participants read an extract. In a subsequent study, these logos increased the likelihood that individuals would purchase products that conserve time—such as a 2 in 1 shampoo. The final study showed these logos also increased temporal discounting: That is, after exposure to these logos, participants often preferred smaller rewards now to larger rewards in the future.

According to Zhong and DeVoe (2010), individuals associate fast food with impatience. Fast food enables individuals to consume food rapidly and, thus, is associated with haste and impatience rather than a willingness to wait. Exposure to fast food, hence, elicits an inclination towards impatience—and may, thus, promote narcissism.

In addition to physical features in the environment, nearby catastrophes may also affect levels of temporal discounting. As Li et al. (2011) revealed, after people hear about a tragedy in their vicinity, they are especially likely to prefer modest rewards now over larger rewards in the future. Presumably, after major catastrophes, people feel their life is vulnerable. They feel divorced from their future and instead overestimate the importance of their immediate needs.

In this study, published in the Journal of Applied Social Psychology, just over 100 individuals completed an instrument six months before and two months after an earthquake of magnitude 8.0 on the Richter scale in Wenchuan, China during 2008. The participants lived in Beijing, about 2000 km away. They received a series of questions, such as whether they prefer 100 yuan now or 120 yuan in one year as well as whether they prefer to lose $1000 yuan now or lose yuan $2000 in one year. After the earthquake, participants were especially likely to prefer a moderate amount now than a larger amount later (Li et al., 2011).

Determinants of temporal discounting: gratitude

Feelings of gratitude tend to curb temporal discounting—and may thus diminish narcissism. In one study that DeSteno et al. (2014) published, participants were instructed to recall and write about an event that had evoked gratitude, happiness, or neutral emotions. Next, participants needed to decide which of various choices they would prefer, such as $11 now or $25 in one month. To motivate participants, individuals were informed that some participants would actually be granted this money. Relative to the other conditions, gratitude increased the degree to which participants were willing to delay gratification and choose a larger reward in the future instead of a smaller reward now.

Arguably, gratitude evolved to facilitate reciprocal altruism. That is, communities can thrive only if individuals who receive assistance from someone now will reciprocate this help in the future. Gratitude may have been the emotion that evolved to motivate this reciprocity in the future. Therefore, people tend to associate gratitude with delayed gratification: the notion that helpful acts now will and should be rewarded in the future. Gratitude, therefore, should prime delayed gratification and reduce temporal discounting.

Individual determinants of collective narcissism

A low self-esteem

Many researchers and scholars have ascribed collective narcissism—the tendency of some individuals to perceive their nation, community, or group as special and worthy of greater respect—to a low self-esteem (e.g., Adorno, 1997; Golec de Zavala et al., 2019). According to this reasoning, if people experience a low self-esteem, they feel unworthy, and they associate themselves with failure or insignificance. These associations tend to elicit unpleasant emotions. To overcome these unpleasant emotions, individuals attempt to define themselves by some collective—such as a nation, ethnicity, or community—and then attempt to perceive this collective as superior. Hence, they feel more worthy and significant, diminishing unpleasant emotions.

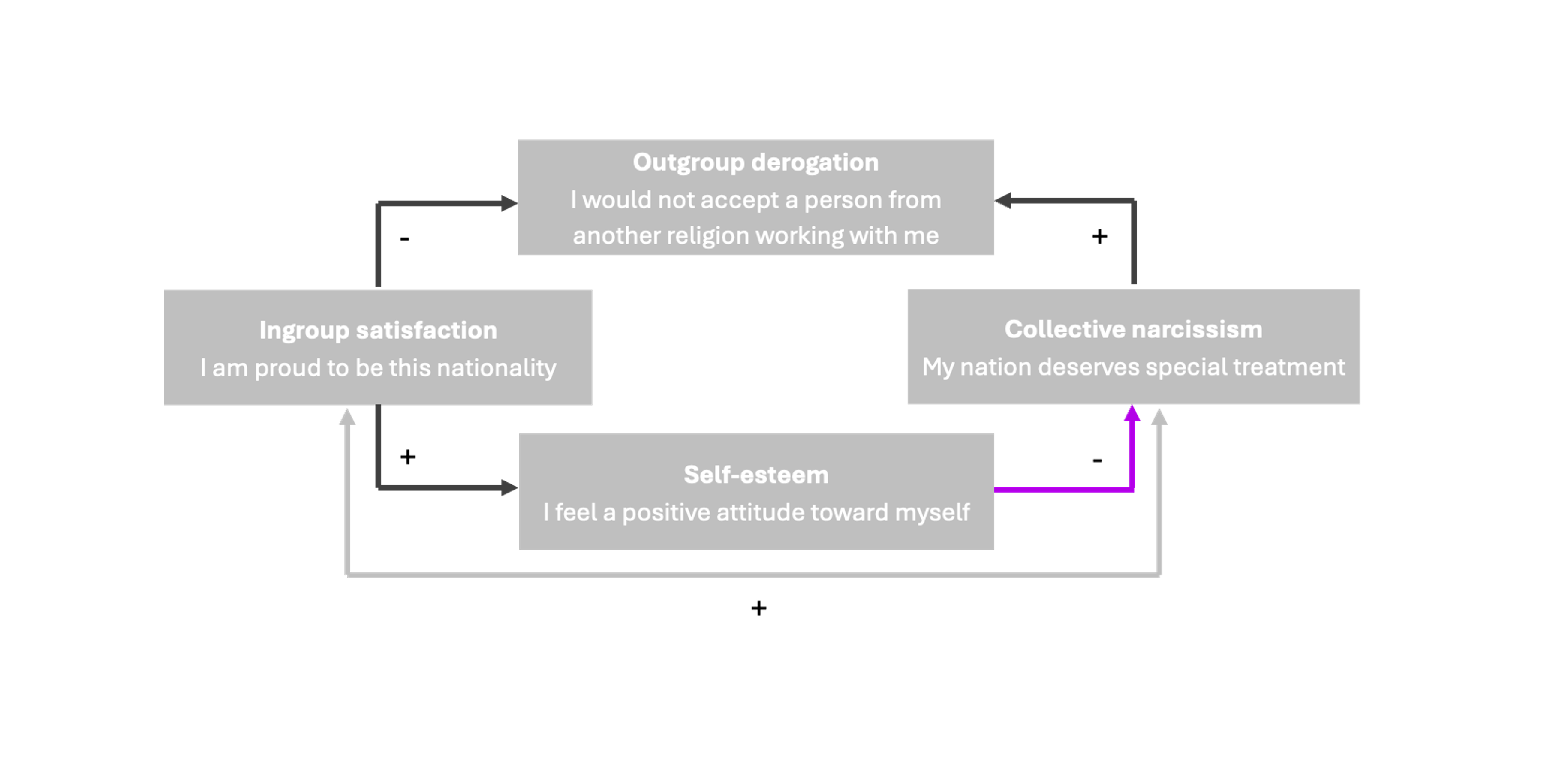

Although this rationale might seem plausible, in the first two decades of this century, research did not uncover significant relationships between collective narcissism and self-esteem (Golec de Zavala et al., 2009; Golec de Zavala et al., 2016). However, Golec de Zavala et al. (2020) later uncovered the reason that collective narcissism does not appear to be associated with self-esteem in empirical studies. Specifically, these authors proposed the model that appears in the following schematic.

This model differentiates collective narcissism and ingroup satisfaction. Specifically, whereas collective narcissism mainly coincides with derision of other communities, ingroup satisfaction primarily coincides with the feelings of pride individuals experience towards their own community. Collective narcissism and ingroup satisfaction are thus more indicative of outgroup hate and ingroup love, respectively. As this theory reveals,

- collective narcissism—emanating from an attempt to overcome feelings of insignificance or failure—should thus be associated with low self-esteem,

- yet, ingroup satisfaction, or the degree to which individuals perceive their community favourably, should be positively associated with self-esteem,

- similarly, collective narcissism, almost by definition, should coincide with the tendency to denigrate other communities,

- however, ingroup satisfaction tends to diminish this denigration of other communities perhaps because the group can foster a sense of resilience; so, other communities are not as likely to seem threatening,

- despite these disparities, collective narcissism and ingroup satisfaction both are indicative of favourable attitudes towards the group and thus should be positively associated with each other.

This model generates some testable hypotheses. Specifically

- the direct pathway between collective narcissism and self-esteem—that is relationship between collective narcissism and self-esteem after controlling ingroup satisfaction, as depicted by the purple arrows—should be negative,

- the indirect pathway between collective narcissism and self-esteem, as depicted by the grey arrows, should be positive,

- the direct pathway and indirect pathway may nullify each other, and hence the correlation between collective narcissism and self-esteem may approach zero—explaining past studies in this literature,

- similar arguments may apply to the association between collective narcissism and outgroup derogation.

Golec de Zavala et al. (2020) conducted a series of seven research studies that corroborate this model. These studies include correlational, longitudinal, and experimental designs. In most of these studies, participants, who were typically Polish or American, completed measures of

- collective narcissism, such as “My group deserves special treatment”,

- ingroup satisfaction, such as “I am glad to be Polish” (cf., Leach et al., 2008)

- self-esteem, and

- outgroup derogation, such as ““I would accept a Jewish person being my neighbour [reverse-scored] or measures of symbolic aggression, in which participant imagine a doll that represents another religion, such as Islam, and indicate the degree to which they would pierce this doll with a pin (Dewall et al., 2013).

In general, the results confirm the hypotheses. That is, collective narcissism was inversely related to self-esteem when ingroup satisfaction is controlled but not related to self-esteem when ingroup satisfaction is not controlled.