Interventions that promote self-transcendence

Self-transcendence refers to moments in which individuals do not confine their attention to personal needs and goals—but, instead, feel a greater concern or affiliation with other people, other generations, other species, or the natural world in general. This notion of self-transcendence overlaps considerably with humility (Tangney, 2000). Consequently, initiatives or interventions that promote self-transcendence should also foster humility.

Self-transcendence workshops and interventions

Researchers have designed workshops and interventions that are specifically designed to promote self-transcendence in various populations, such as adolescents or elderly individuals. To illustrate, Russo et al. (2022) designed an intervention, comprising four tasks, that induces this self-transcendence in adolescents. Here were the four tasks:

- First, the participants read an article on research that shows that adolescents who consider other people—such as assist individuals and experience compassion—tend to experience greater wellbeing and satisfaction with life. Furthermore, the article reveals that adolescents are more inclined to be helpful and compassionate than many teenagers assume.

- Second, the participants received a list of common helpful behaviours, such as apologising to someone, offering advice, providing support to a person who feels distressed, helping a friend in need, thanking a friend or relative, and so forth. These participants were invited to specify, privately, which of these behaviours that have initiated in the past 18 months. This exercise is designed to prime memories of helpful or prosocial behaviours.

- Third, participants were invited to recall and to describe a moment in which they had been helpful to someone. Specifically, they were prompted to also remember and transcribe the emotions they felt during this experience, such as relief, pride, or empathy.

- Finally, participants were invited to transcribe a message they could communicate to convince friends, classmates, or other peers about the importance of such helpful, pro-social behaviour.

As Russo et al. (2022) revealed, in general, participants who reported self-transcendent values were more likely to assist other people during the COVID-19 pandemic. This relationship, however, was significant only in participants who completed this series of four tasks. Presumably, these four tasks elicit memories or inclinations that epitomise self-transcendence.

Culture

In lieu of training and similar interventions, more enduring cultural practices or norms could also promote self-transcendence. Indeed, Let and Levenson (2005) confirmed that culture may affect the prevalence of self-transcendence. For example, in cultures that are especially individualistic and competitive, people tend to orient their attention to personal, immediate needs, diminishing self-transcendence.

The role of nature and awe in self-transcendence

Exposure to nature

Rather than deliberate interventions, incidental life experiences may also foster self-transcendence. For example, as many studies have revealed (e.g., Guo et al., 2024; Mei et al., 2024), exposure to nature can elicit feelings of self-transcendence. To illustrate, in one study, conducted by Castelo et al. (2021), participants completed a survey. Half the participants were asked to remember the last time they felt embedded in nature. To reinforce this exposure to nature, the survey these participants received also displayed a forest in the background. The survey invited all participants to answer questions about

- the degree to which they orient their attention to the needs of other people,

- the extent to which they orient their attention to their personal needs, interests, and concerns,

- the degree to which they like to help other people, called prosocial attitudes.

Compared to participants who were not exposed to nature, participants who were exposed to nature demonstrated greater orientation to the needs of other people instead of themselves. Furthermore, this orientation to other people mediated the association between exposure to nature and prosocial attitudes.

Awe: An introduction

Researchers have proposed several reasons that exposure to nature may foster self-transcendent emotions. According to one account, exposure to nature may elicit a sense of awe and wonder (Ballew & Omoto, 2018). That is, natural environments tend to be vast, intricate, and thus remarkable—and remarkable scenes or experiences tend to elicit awe. Individuals associate awe with a sense they are small in comparison. Individuals who experience awe, therefore, become more attuned to their surroundings rather than merely their immediate and personal needs, tantamount to self-transcendence.

Consistent with this account, research has revealed that exposure to nature does indeed elicit feelings of awe (Ballew & Omoto, 2018). And feelings of awe elicit a sense of self-transcendence (Dai & Jiang, 2024). In one study, conducted by Dai and Jiang (2024), some participants were invited to recall an experience that elicits awe—an experience in which they perceived vastness and felt compelled to adapt their assumptions to accommodate this moment. In the control condition, participants recalled the previous time in which they washed their clothes. Subsequently, participants completed a short measure that gauges self-transcendence. For example, participants indicated the degree to which they agree with four statements, such as “Right now, I want to find answers to some universal spiritual questions”. The findings revealed that a sense of awe elicited self-transcendence.ing values instead of their immediate needs. These enduring values generally orient the attention of people to the needs of other individuals, generations, or times, epitomising self-transcendence.

Awe: Positive versus threatening variants

Since the mid 2010s, researchers began to distinguish positive awe and threatening awe (Gordon et al., 2017; Sawada & Nomura, 2020). Specifically,

- individuals experience positive awe when exposed to remarkable beauty, virtue, or benevolence,

- individuals experience threatening awe when exposed to frightening or threatening material instead, such as videos of natural disasters or narratives about dictators.

In a pair of enlightening studies, Zhao et al. (2026) explored the impact of positive awe and threatening awe on various facets of self-transcendence, such as connectedness to humanity and a sense of feeling small. In the first study, 36 participants were invited to recall occasions that elicited positive awe, threatening awe, or no awe, depending on the condition to which they had been assigned. Specifically, these participants were prompted to

- recall a time in which they experienced intense awe because of beautiful landscapes such as huge waterfalls, inspiring people such as Nelson Mandela during the end of apartheid, or mysterious wonders such as space,

- recall a time in which they experienced intense awe because of natural disasters, such as earthquakes, or destructive people, such as Adolf Hitler,

- recall the time they last completed their laundry.

Next, participants answered a series of questions that measure various facets of self-transcendence including

- a feeling of connectedness to all living beings and the world, typified by items like “I experienced a sense of oneness with all things” (cf Yaden et al., 2019),

- a positive sense of feeling small, illustrated by items like “I felt small in the grand scheme of things” or “I felt humble relative to something more powerful than myself”,

- a negative sense of feeling trivial, exemplified by items like “I felt I did not matter anymore”.

As the findings revealed,

- participants who experienced threatening awe felt less connected to the world than did participants who experienced positive awe but more connected than did participants who experienced no awe,

- relative to the control condition, both variants of awe, to similar degrees, increased the extent to which participants experienced a positive sense of feeling small and decreased the extent to which participants experienced a negative sense of feeling trivial (Zhao et al., 2026).

The second study was similar except, to elicit positive awe, threatening awe, or no awe, the researchers invited participants to watch relevant videos. This study generated the same pattern of findings as the previous study. Arguably,

- the pleasant feelings that coincide with positive awe may foster trust and thus connectedness

- in contrast, both positive awe and threatening awe may remind individuals of who they are relative to the enormity and intricacies of the world,

- yet feelings of awe may saturate this sense of smallness with a feeling of hope and possibility rather than dejection or despair.

Authenticity

Besides awe, other accounts could also explain the association between nature and self-transcendence. For example, some research indicates that nature elicits a sense of authenticity—a state in which individuals feel their actions and choices in life primarily depend on their true values instead of the demands of other people. And this sense of authenticity promotes self-transcendence.

Research has indeed confirmed that nature fosters authenticity. In one study, for example, reported by Yang et al. (2024), participants watched a video recording of either a natural environment, such as forests, or an urban environment. Next, participants completed a measure of self-esteem as well as a series of questions that assess authenticity, such as “Right now, I am true to myself”. Participants who were exposed to a natural environment were more likely to experience authenticity. Self-esteem mediated this association.

Presumably, in natural environments, such as forests, the worries and anxieties of individuals tend to dissipate as their usual pressures and concerns abate. As these worries and anxieties subside, individuals may be more attuned to their strengths, capabilities, and achievements, enhancing their self-esteem. After their self-esteem rises, people may be more inclined to trust their values and choices. They do not, therefore, feel the need to accommodate other people but will reach decisions that correspond to their values or inclinations, manifesting as authenticity.

This authenticity also tends to promote self-transcendence, as Toper et al. (2024) confirmed. In this study, 129 Turkish adults completed a survey that measured authenticity, self-transcendence, and environmental behaviour. The measure of authenticity comprised 12 items that assessed three facets:

- self-alienation, such as “I feel as I don’t know myself very well”,

- authentic living, such as “I think it is better to be yourself than to be popular”, and

- accepting external influence, such as “I am strongly influenced by the opinions of the others”.

Authenticity was operationalised as low levels of self-alienation and accepting external influence as well as high levels of authentic living. The self-transcendence scale, as developed by Reed (1991), measured the self-transcendence of participants. As the findings revealed, authenticity was positively associated with self-transcendence. In addition, self-transcendence mediated the association between authenticity and environmental behaviours like recycling.

Presumably, when individuals feel authentic, they choose actions that are compatible with their enduring values. They are thus more attuned to these enduring values instead of their immediate needs. These enduring values generally orient the attention of people to the needs of other individuals, generations, or times, epitomising self-transcendence.

Practices that may foster the experience of flow

After individuals experience flow—a state in which people feel utterly absorbed in an interesting and challenging task (Csikszentmihalyi, 2000)—they may be more likely to experience humility. To illustrate, soon after individuals recall times in which they experienced flow, they are more likely to demonstrate intellectual humility, openness to change, and wise reasoning during conflicts (Kim et al., 2023). Presumably, this experience of flow diverts the attention of individuals from their immediate problems and needs. Their immediate problems or needs do not seem as significant. Therefore, these individuals are more willing to contemplate their limitations, consider alternative perspectives, and demonstrate other hallmarks of humility. Conditions or circumstances that promote flow should thus also foster humility.

Introduction to flow

In essence, when individuals feel they have developed the skills and capabilities they need to complete a specific, challenging task, they often experience flow while they undertake this activity. When individuals experience flow (Nakamura & Csikszentmihalyi, 2002),

- their concentration is intense and sharp,

- they often underestimate, but can also overestimate, the passage of time, partly because the task seems inherently fascinating,

- they feel a sense of agency and confidence,

- they are not as concerned about impressing anyone else.

The balance hypothesis

According to the balance hypothesis, flow inspires people to enhance and to refine their skills (Csikszentmihalyi, 1993). That is, whenever individuals apply skills they have recently developed to novel and challenging events, they experience this state of flow. Because this state is pleasurable, individuals may naturally gravitate to further opportunities that elicit flow. Therefore, over time, these individuals become more inclined to apply these skills in challenging circumstances, refining and extending these capabilities as well as enhancing their productivity.

These benefits of flow imply that individuals are more likely to experience this state in specific circumstances. Specifically, people experience flow when

- the task they need to complete is unambiguous—and hence these individuals can ascertain which skills they should apply to achieve this goal,

- the task is challenging to the individual and demands their most advanced skills,

- individuals can readily ascertain whether they have completed this task; that is, the feedback is unambiguous and immediate.

In short, as this argument implies, when the advanced skills of individuals and the elevated demands of a task match, people are more likely to experience flow. This argument is thus called the balance hypothesis (Massimini & Carli, 1988; Nakamura & Csikszentmihalyi, 2002)

Many studies corroborate this hypothesis. For example, in a study that Keller and Bless (2008) conducted, participants attempted the computer game called Tetrus. The difficulty of this task was manipulated. Participants were more likely to manifest the state of flow, such as underestimate the time that had elapsed, when the task felt moderately difficult. Thus, as hypothesised, whenever the skills of individuals roughly matched the demands or challenges of this task, participants were more likely to experience flow.

As Ceja and Navarro (2009) underscored, many other characteristics of individuals, attributes of the task, or features of the circumstances affect the likelihood of flow. Nevertheless, the balance hypothesis presupposes that many of these characteristics, attributes, or circumstances will shape the degree to which individuals perceive the task as challenging but achievable.

The four-challenge model

The balance hypothesis implies that a blend of elevated skills and challenging tasks elicits flow. The four-challenge model, first proposed by Csikszentmihalyi (1975), also characterises the emotion or state that individuals experience if either their skills on this activity are not advanced or the task is not challenging. Specifically, according to this taxonomy

- when the relevant skills of people are limited but the task is challenging, these individuals tend to experience anxiety, because they feel unable to achieve their goals,

- when the relevant skills of people are not advanced and the task is simple, individuals tend to experience apathy,

- when the relevant skills of people are advanced but the task is simple, individuals tend to experience boredom—an emotion that tends to emanate from unfulfilled opportunities.

Lambert et al. (2013) outlined and validated a refined variant of this four-channel model called the experience fluctuation model. Specifically, they divided level of skill and level of demand into three levels rather than two levels. That is, rather than differentiate only low or high levels of skills and demand, these researchers also introduced a moderate level. To illustrate,

- when the relevant skills of people are moderate but the task is simple, individuals experience relaxation,

- when the relevant skills of people are moderate but the task is challenging, individuals experience arousal,

- when the relevant skills of people are limited but the task is moderately challenging, individuals experience worry, and

- when the relevant skills of people are advanced but the task is moderately challenging, individuals experience a sense of control.

This model does generate one significant implication. As Lambert et al. (2013) revealed, some of the experiences that researchers typically ascribe to flow are observed when people experience control instead—that is, when individuals utilise advanced skills to complete a moderately challenge task. In this study, 7 to 10 times a day, participants were told to complete some questions about their existing state. In particular, they were asked to indicate the extent to which they perceived the situation as challenging and the degree to which they felt they had developed the skills to meet this challenge. In addition, manifestations of flow, including enjoyment, concentration, happiness, and intrinsic motivation, were assessed. Enjoyment, happiness, and intrinsic motivation, but not concentration, were actually more likely to be observed when participants experienced control rather than flow.

Measures of flow

Researchers have developed and utilised a range of measures to gauge flow. Jackson and Eklund (2002), for example, designed a comprehensive measure, comprising 36 items, that assesses the nine key facets of flow (Csikszentmihalyi, 2000). These facets include

- a balance between level of skill and level of challenge,

- a merge between awareness and action—in contrast to a common experience in which people think about past or future events,

- clarity on the goals or purpose the individual needs to pursue,

- unambiguous feedback,

- concentration directed to the relevant task,

- a sense of control,

- a loss of self-consciousness—in contrast to a concern about how people might appear,

- a distorted sense of time,

- the sense the task is intrinsically rewarding, called an autotelic experience.

The consequences and determinants of flow vary across these nine facets. For example, when individuals engage in exercise, increasing their effort from 50% to 100%, this maximum level tends to increase both concentration and, to a lesser extent, the autotelic experience. The same increase in effort, however, tends to curb the clarity of goals (Connolly & Tenenbaum, 2010).

Simple interventions to promote flow: Challenging goals

Some researchers have designed and assessed simple interventions to promote flow—interventions that might thus foster humility as well. For example, in one study, conducted by Weintraub et al. (2021), half the participants completed a series of exercises that were designed to promote flow. Every morning, at 8 am, over five days, these participants received a message on their smartphone. The message prompted the participants to set three challenging but achievable goals they plan to complete during the day. These goals should be specific, measurable, attainable, and relevant to their lives. The message included a few examples to illustrate these instructions.

This simple experience significantly increased the level of flow these participants experienced, relative to individuals who had not set these goals. The experience also diminished stress and augmented engagement. Presumably, this exercise increased the likelihood that individuals would pursue challenging but attainable goals.

Simple interventions to promote flow: Job crafting

Rather than invite people to set challenging but attainable goals, other interventions utilised the principle of job crafting—in which workers deliberately change their tasks or role to enhance wellbeing, motivation, and engagement. In one study, conducted by Costantini et al. (2020), participants first attended a workshop, about job crafting, lasting four hours. During this workshop, they learned about the notion of job crafting, the benefits of job crafting, the boundaries or limitations of job crafting, as well as examples of how people may craft or adjust their tasks to enhance wellbeing.

Some examples revolved around how individuals could utilise job resources more effectively to fulfill challenging goals—such as advice, feedback, or support they could receive from colleagues, novel activities they could attempt, skills they could gradually refine, or rewards they could award themselves. Other examples revolved around how individuals could diminish the demands at work, such as clarify expectations or defer some deadlines. Participants discussed the benefits and drawbacks of both their past attempts to craft their jobs and future plans on how to craft their jobs

Furthermore, during this workshop, participants considered social norms around job crafting, such as whether managers embrace or disapprove these attempts as well as the prevalence of these strategies in the workplace. Finally, participants identified a buddy or colleague at the organisation with whom they could identify opportunities to craft their jobs.

A week later, participants attended a second workshop, lasting 3 hours, around how to translate their goal to craft jobs into action. First, participants recorded plans on how they will implement each job crafting strategy, such as the behaviour they will implement, the day they will implement this plan, and other relevant features of the setting. These attempts to relate a strategy to a specific circumstance is called an implementation intention. Next, participants indicated some possible barriers that might disrupt these plans and strategies to overcome these barriers.

This intervention subsequently increased the degree to which individuals felt absorbed in their tasks—a feature of flow. Presumably, job crafting enables individuals to plan tasks that are challenging but not overwhelming.

Simple interventions to promote flow: Humour

Other research has shown that interventions that revolve around humour might also increase the likelihood that staff experience flow. Bartzik et al. (2021) reported a seminal research study on this topic. In this study, nurses attended a workshop, lasting three hours, that was designed to encourage these participants to utilise humour when interacting with patients, relatives of patients, and colleagues. Participants were able to maintain more humour in their interactions six months later. This humour increased the frequency with which these nurses experienced flow as well as enhanced the degree to which their work seemed meaningful and enjoyable.

Arguably, humour can elicit a sense of fun at work. When individuals perceive work as fun, challenges that might initially seem overwhelming initially might subsequently feel more attainable. This fun might improve creativity, enabling individuals to resolve problems, diminish job demands, and increase the feasibility of their tasks.

Features of jobs that promote flow

Some tasks or activities are especially likely to induce flow. For example, when employees plan future tasks, solve important problems, or evaluate alternatives, they become more likely to experience flow (Nielsen & Cleal, 2010). In particular, planning instils a sense of control over the environment, evoking flow. Problem solving and evaluation invoke a vast range of skills, also inducing flow.

Because these tasks often elicit flow, this state is more prevalent during work than leisure time (Czikszentmihalyi & Lefevre, 1989). That is, during work, the tasks are usually sufficiently challenging to generate flow. According to one study, employees experience flow 44% of the time at work, boredom 20%, and anxiety the remaining 36% (Donner & Czikszentmihalyi, 1992). Indeed, flow is even more elevated in managers (Donner & Czikszentmihalyi, 1992).

Besides the goal of tasks, various characteristics of tasks can also elicit flow. For example, individuals are more likely to experience flow if

- they are granted autonomy and, for example, can choose which methods they will use to complete tasks (Demerouti, 2006),

- they can utilise a variety of skills to complete their tasks (Demerouti, 2006),

- their task feels important, generating a discrete and significant outcome (Demerouti, 2006).

These job characteristics, presumably, mobilise the motivation individuals need to complete challenging tasks. In addition, these job characteristics orient the attention of individuals to the task and not to distractions, such as other people.

Characteristics of individuals that affect flow: Achievement flow motivations

According to Baumann and Scheffer (2010), the primary individual trait or tendency that determines whether people are likely to experience flow is called an achievement flow motive. To clarify, motives are derived from the various actions that individuals have learnt to apply in specific circumstances. Often, across a variety of circumstances, a particular subset of behaviours, such as intimate conversations, tends to be reinforced. Individuals thus feel inclined to enact these behaviours in many settings, manifested as motives.

These motives tend to differ across individuals. Some individuals, for example, often strive to improve intimacy. Other individuals feel motivated to attract attention, to avert rejection, to seek familiar people, to gain status, to influence other people, or to gain independence. Hence, many of the motives of individuals relate to affiliation or power.

In addition to affiliation or power, many of the motives that guide individuals revolve around achievement instead. Individuals, for example, can be motivated to fulfill standards of excellence, cope with failure, avoid disappointment, or experience a sense of flow.

Thus, the flow motive is only one of many different motivations that might be invoked. According to Baumann and Scheffer (2010), the flow motive comprises two distinct, but interrelated, facets: the motivation to seek challenges and the motivation to master or resolve these difficulties.

In a series of studies, Baumann and Scheffer (2010) administered the operant motive test to assess and characterise this flow motivation. Specifically, participants observed a series of schematic illustrations. One illustration, for example, depicted a person seemingly climbing a hill. Another illustration portrayed two people near a series of rectangular items, positioned on a table. Participants were asked questions, like “What is important for the person in this situation?”, “How does the person feel and why?”, as well as “How does this story end”.

If individuals experience a flow motivation, their need to seek difficulties and their need to master challenges are likely to be activated. These needs should then shape their responses to these questions. The participants might, for example, contend that perhaps the protagonist is feeling invigorated and enthralled as they master this task. Thus, allusions to positive feelings of curiosity, interest, excitement, concentration, absorption, challenge, variety, or stimulation while learning manifest this need to seek and to master difficulties, representing a flow motivation.

In one study, Baumann and Scheffer (2010) explored whether tangible incentives compromise this achievement flow motive. That is, sometimes, individuals are motivated by a sense of fascination, challenge, and interest, called intrinsic motivation. In contrast, on other occasions, individuals are motivated by tangible incentives, such as money or status. In this state, individuals monitor the needs of other people, rather than undertake the tasks they inherently prefer, compromising flow.

According to this account, intrinsic motivation, and not tangible incentives, should guide the choices of individuals who experience flow motive. These individuals should be aware of their own preferences. They should not, therefore, confuse their own preferences with the constraints that are imposed by anyone else—a confusion that is sometimes called self-infiltration.

Baumann and Scheffer (2010) indeed showed that self-infiltration is inversely associated with this achievement flow motive. To assess self-infiltration, participants were instructed to decide which of 48 clerical tasks they would prefer to complete. Next, the experimenter indicated some other tasks the participants need to complete. Later, participants were asked to recall which tasks they chose. If participants demonstrated an achievement flow motive, they could more readily remember which tasks they chose, demonstrating negligible self-infiltration. They were more cognisant of their own preferences.

These findings imply that individuals who often seek and master difficulties can identify which goals are derived from preferences that evolved from past experiences. The implementation of these plausible goals may underpin the experience of flow.

Characteristics of individuals that affect flow: Locus of control

A variety of individual characteristics may affect the inclination of people to pursue an achievement flow motivation, to experience flow, and to demonstrate humility. Keller and Blomann (2008), for example, showed that individuals who feel their success and satisfaction depends on events they cannot control, called an external locus of control, are not as likely to experience flow. Presumably, the attention of these individuals may be oriented towards other people and events, instead of their own private needs or pursuits, compromising flow.

Characteristics of individuals that affect flow: Temperament

The temperament of individuals—that is, how individuals tend to appraise and respond to information—may also influence the frequency of flow. In one study, published by Teng (2011), participants completed a measure that assesses four facets of temperament that tend to be largely heritable: harm avoidance, novelty seeking, reward dependence, and persistence. Participants also completed a measure of flow, comprising three items.

Novelty seeking was positively associated with flow. That is, individuals who like to explore unusual and novel activities, events, and objects tended to report more flow. Furthermore, persistence was also associated with flow. Taken together, these findings might imply that people who seek novelty and persist despite obstacles are more likely to embrace challenging experiences. This inclination to embrace challenge enhances the skills of individuals as well. This combination of challenge and skill is regarded as the cardinal source of flow.

Characteristics of individuals that affect flow: Coping styles

In stressful and challenging circumstances, individuals can apply a range of strategies to manage their emotions and concerns. For example, as the Mini-COPE inventory implies (Carver et al., 1997), to cope with stress, people may apply 14 coping strategies such as

- planning, in which they plan how they will respond carefully, illustrated by items like “I have been thinking hard about what steps to take”, exemplified by items like “”,

- positive reframing, in which they attempt to consider the benefits of these circumstances, measured by items like “I have been trying to look for something good in what is happening”,

- acceptance, in which they learn to accept or withstand the discomfort, assessed by items like “I have been learning to live with it”,

- use of emotional support, in which they seek comfort from other people, illustrated by items like “I have been getting comfort and understanding from someone”,

- denial, in which they convince themselves the problem is trivial, exemplified by items like “I have been refusing to believe that this has happened”,

- venting, in which they express their frustrations, measured by items like “I have been expressing my negative feelings”, and

- behavioural disengagement, in which they do not even attempt to cope, illustrated by items like “I have been giving up the attempt to cope”.

Arguably, the coping strategies that individuals apply during challenging tasks could affect the level of flow they experience (Wojtasiński et al., 2026). Specifically, if individuals apply coping styles that are helpful in the circumstances, they may perceive the task as challenging but feasible—a perception that tends to promote flow. In contrast, if individuals apply coping styles that revolve around denial or avoidance, they may vacillate between dissociation from the challenge and feelings of panic and anxiety. Consequently, they will deem the task to be insignificant or overwhelming, impeding flow.

Wojtasiński et al. (2026) conducted a comprehensive study that explores the relationship between coping styles and flow. In this study, 528 members of board game clubs completed an online survey, hosted in Google Forms. The online survey comprised two main scales. First, participants were instructed to consider their experiences while playing board games and then completed the Flow Short Scale (Rheinberg et al., 2003; Engeser & Rheinberg, 2008). This scale measures two facets of flow:

- absorption, epitomised by items like “I am completely immersed in what I am doing”, and

- fluency, epitomised by items like “I know exactly what I have to do at every moment”.

In addition, participants completed the Mini-COPE inventory (Carver et al., 1997) to measure how these individuals cope with the stress. The researchers utilised a range of techniques to analyse the data, revolving around a gaussian graphical model (e.g., Epskamp et al., 2018). In essence, the researchers discovered that

- planning was positively associated with absorption, and

- planning and acceptance were positively associated with fluency, whereas behavioural disengagement was negatively associated with fluency (Wojtasiński et al., 2026).

Accordingly, when completing stressful and challenging tasks, individuals should perceive the activity as an opportunity to learn, fostering acceptance. They should then plan carefully how they will complete the task and how they will learn from this opportunity. When people apply these coping styles, they perceive the task as a surmountable and worthwhile challenge. Tasks that are perceived as a surmountable challenge tend to elicit flow.

Characteristics of workplaces that promote flow: Leadership tools

Some features of workplaces may promote experiences of flow. For example, Buzady et al. (2024) validated an online game that teaches leaders how to promote flow in their organisations, called FLIGBY, or Flow is Good Business For You, developed by Csikszentmihalyi.

Each participant assumes the role of a leader at a company, called “Flow Consulting”. Participants play the game alone but pretend to be guiding a team. Their goal is to help a team navigate various challenges and to elicit flow in these members. Throughout the game, leaders need to reach decisions that resemble everyday choices in workplaces—derived from a pool of over 150 scenarios. For example, leaders may need to assign tasks to staff, address concerns about performance, and encourage collaboration. These decisions affect the motivation, engagement, and flow experiences of their staff.

The team consist of various fictional characters, each demonstrating unique preferences, talents, and limitations. Leaders need to adapt their style to accommodate these traits, to fulfill deadlines, to solve conflicts, and to boost morale. The leaders must balance authority with empathy as well as clarity with autonomy or flexibility.

After each decision, leaders receive feedback. The team will thrive to the degree these members experience flow. The literature on flow, such as the importance of intrinsic motivation, together with 29 leadership principles, guides this feedback. ddition to transient emotions or states, more enduring cultural practices or norms could also promote self-transcendence. Indeed, Let and Levenson (2005) confirmed that culture may affect the prevalence of self-transcendence. For example, in cultures that are especially individualistic and competitive, people tend to orient their attention to personal, immediate needs, diminishing self-transcendence.

Practices that may foster gratitude

As research has revealed, gratitude tends to foster humility (Krumrei Mancuso et al., 2024) as well as many other benefits, such as reductions in systolic blood pressure (Leavy et al., 2025). To promote gratitude and thus humility, researchers have recommended and validated a range of practices, such as gratitude diaries, gratitude letters, and other activities (for recommendations on the practices that workplaces could implement, see Fehr et al., 2017). Not all these practices are equally helpful, however. For example, as research has discovered, to experience gratitude, individuals should

- write one or more paragraphs, rather than merely a few words or a sentence, about why they feel grateful to someone (Regan, et al 2023); more extensive narratives improve wellbeing more than do lists,

- in addition to writing about the people to whom they feel grateful, individuals could also write about the gratitude they feel towards their health, the basic needs in their life that are fulfilled—such as a roof over their head or clean water—as well virtues they value in society, such as freedom or kindness (Purol & Chopik, 2024); these topics were especially likely to promote gratitude and wellbeing in one study.

My Best Self 101: Outline of the program

My Best Self 101 is one of the most comprehensive resources that was designed to foster gratitude. The developers recommend that participants dedicated 20 minutes a day to this module over three weeks. During the first week, participants mainly read the materials about gratitude. These materials define gratitude, outline the benefits of gratitude, explains why gratitude is helpful, and so forth. During the second week, participants mainly apply one or more of the nine practices this module recommends. These practices include

- gratitude journaling, in which individuals maintain a diary of the people and facets of their life for which they are grateful,

- gratitude letters, in which individuals write a letter of gratitude to someone for whom they are grateful (e.g., Hosaka & Shiraiwa, 2021; Toepfer et al., 2012),

- a gratitude meditation, in which individuals listen to a guided meditation that inspires gratitude to various facets of their life,

- gratitude reminders, in which individuals set an alarm on their smartphone, in which they are reminded two or three times a day to consider facets of their life to which they are grateful,

- informal opportunities, in which individuals, throughout the day, imaginatively seek opportunities in which they can express their gratitude—such as conceal notes of appreciation in a lunch bag,

- writing prompts, in which individuals answer questions that are designed to prompt gratitude—such as a time in which a potential tragedy was averted, a favourable event that happened today, or a quality of someone for which they are grateful

- the “I appreciate” exercise, in which individuals first identify three characteristics they like about someone and then share this information to the person,

- negative visualisation, in which individuals are invited to imagine their life without a person or facet they appreciate (adapted from Gottman, 2018),

- the Gratitude Journal 365 app—an app that comprises a range of strategies to foster gratitude.

The benefit of this approach, relative to many other gratitude interventions, is that participants can choose a variety of strategies and practices, diminishing monotony and accommodating their needs or preferences at any time (cf., Davis et al., 2016).

My Best Self 101: Evidence of validity

Deichman and Warren (2025) validated the My Best Self 101 gratitude module, revealing this approach is more effective than gratitude journaling. In this study,

- 117 adults completed the My Best Self 101 gratitude module, dedicating 20 minutes a day to this website for 3 weeks,

- another 135 adults instead completed only one of the 9 strategies: gratitude journaling,

- participants then completed several measures of gratitude, such as the gratitude adjective checklist (Emmons & McCullough, 2003), the Gratitude Questionnaire (McCullough et al., 2002), and the Gratitude, Resentment, and Appreciation Test (Watkins et al., 2003),

- finally, participants completed various measures of wellbeing, such as the Positive and Negative Emotion Scale (Serafini et al., 2016) and the Survey on Flourishing (Linford & Warren, 2023).

After participants completed the My Best Self 101 gratitude module or gratitude journals, the degree to which they felt grateful and their wellbeing improved. As hypothesised, these improvements were more pronounced in participants who completed the My Best Self 101 gratitude module.

Gamified Interactive Gratitude Practice: Outline of the intervention

To foster gratitude, Emmons and Mccullough (2003) recommended that people should record three grateful experiences every day—such as a helpful friend or the warm sun, heating their face. However, as two meta-analyses have revealed, the benefits of gratitude interventions, relative to other active treatments, on various indices of mental health are only modest (Davis et al. 2016; Dickens, 2017). According to Deng et al. (2025), gratitude interventions may be repetitive and tedious, limiting the degree to which people immerse themselves in these activities.

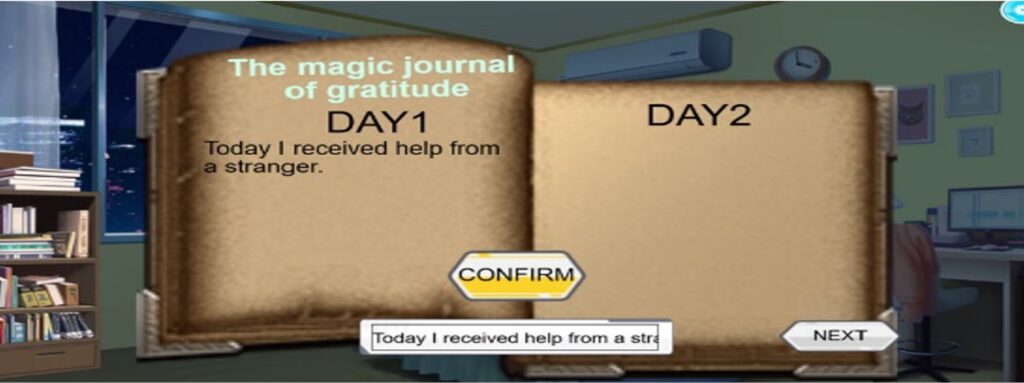

To override this limitation, Deng et al. (2025) designed and validated a gamified variant of this activity, called the Gamified Interactive Gratitude Practice. The interface resembled the following screen.

The game entailed five key features:

- First, participants were immersed in a narrative and informed that a lost alien kitten, called Momo, had arrived at the doorstep. To return the kitten home safely, participants needed to record daily blessings or experiences of gratitude to generate the energy that would power the spaceship.

- Second, to assist participants, Momo first conveyed some helpful guidelines, such as the definition and benefits of gratitude as well as the distinction between gratitude and guilt.

- Third, participants received regular feedback, such as affirmative messages from Momo each time they recorded a gratitude experience.

- Fourth, participants could interact with Momo before contemplating and recording each gratitude experience. For example, Momo would comfort participants who reported unpleasant emotions or relay jokes to participants who reported pleasant emotions.

- Finally, as the following screen shows, the gratitude experiences were recorded and displayed visually, enabling participants to observe the accumulation of records.

Gamified Interactive Gratitude Practice: Evidence of efficacy

Deng et al. (2025) conducted a study to assess whether this intervention—relative to relevant controls—evokes gratitude and improves wellbeing. In this study, 150 participants completed one of three tasks, dedicating about five minutes a day to this task over a week. Depending on the condition in which they had been assigned,

- some participants completed the gamified interactive gratitude practice,

- other participants merely recorded three blessings or gratitude experiences each day but without accessing this gamified interface,

- some participants completed a game in which they interacted with a digital cat, to control the impact of digital engagement.

Before, immediately after, and a month after completing these tasks, participants answered a series of questions, designed to gauge their levels of gratitude and wellbeing. For example, participants completed

- the Gratitude Questionnaire (McCullough et al., 2002) and Gratitude Adjective Checklist (Emmons & McCullough, 2003) to measure the experience of gratitude, comprising items like “I have so much in life to be thankful for” and “(How often do you feel) appreciative”, respectively,

- the Patient Health Questionnaire (Kroenke et al., 2001) and the General Anxiety Disorder-7 (Spitzer et al., 2006) to assess feelings of depression and anxiety respectively—as well as the Satisfaction with Life Scale,

- a set of five questions that measure the degree to which individuals experienced intrinsic motivation while completing the task, such as “I found this practice very interesting”.

The results confirm the efficacy of this gamified intervention. First, the gamified intervention, relative to the two other tasks, elicited greater intrinsic motivation. Second, the gamified intervention increased gratitude and satisfaction with life as well as decreased both depression and anxiety. The improvement in gratitude and diminution in depression also persisted at least a month. Third, some but not all these improvements were more pronounced in participants who played the gamified version than in participants who merely counted their blessings or interacted with a digital cat but did not record gratitude experiences.

Motivations that affect gratitude: The motivation to learn

The motivations of individuals may affect the degree to which they experience gratitude. For example, during the 1970s and 1980s, researchers introduced the distinction between a learning orientation and a performance orientation (see this webpage). In essence,

- when individuals adopt a learning orientation, their primary motivation is to extend their knowledge, skills, and capabilities,

- when individuals adopt a performance orientation, their primary motivation is to demonstrate their capabilities, such as outperform rivals.

Sanchez et al. (2025) proposed the possibility that a learning orientation could promote gratitude to other people. In particular

- when individuals adopt a learning orientation and thus strive to extend their capabilities, they perceive other people as a source of knowledge, feedback, or support and thus prioritise cooperation,

- to facilitate cooperation, individuals become attuned to which colleagues may be a source of support,

- this awareness of support fosters gratitude,

- in contrast, when individuals adopt a performance orientation and thus strive to demonstrate their capabilities, they may perceive other people as rivals,

- therefore, they are not as attuned to the support that other individuals provide.

Sanchez et al. (2025) conducted four studies that validate these premises. In one study, 87 American participants read one of two articles, purportedly designed to test their comprehension. However, the articles were actually constructed to prime either a learning orientation or performance orientation. To illustrate

- to prime a learning orientation, one article revealed that successful people seek challenging assignments and opportunities to learn skills and develop capabilities,

- to prime a performance orientation, the other article revealed that successful people contemplate how they can outperform their coworkers.

After reading the article, participants wrote about an event in which they felt grateful to someone—and then rated their gratitude on a scale from 1 to 11. In addition, participants rated the degree to which they were currently experiencing a range of other emotions. Consistent with the hypotheses, participants who had read the article that was designed to prime a learning orientation, instead of a performance orientation, were more likely to experience gratitude but not the other emotions (Sanchez et al., 2025). A subsequent study revealed that a pro-social motivation—or the motivation to help other people at work—mediated the association between a learning orientation and gratitude.

Motivations that affect gratitude: Regulatory focus

When individuals adopt a learning orientation or a performance orientation, they can either strive to achieve gains, called a promotion focus, or to minimise losses, called a prevention focus. That is,

- when individuals experience a promotion focus, they pursue their hopes and aspirations of the future, striving to improve their life

- in contrast, when individuals experience a prevention focus, they pursue their duties and obligations, striving to prevent complications or losses.

Whether individuals adopt a promotion focus or prevention focus can significantly affect their motivations, emotions, and behaviour (see Higgins, 1997, 1998, 1999, 2000, and 2005). For example, as Mathews and Shook (2013) revealed, a promotion focus can promote gratitude. To illustrate, in one study, 189 undergraduate students completed a batter of online measures including

- the General Regulatory Focus Measure (Lockwood et al., 2002), comprising questions like “I frequently imagine how I will achieve my hopes and aspirations” to measure promotion focus and “In general, I am focused on preventing negative events in my life” to measure prevention focus,

- the Gratitude Questionnaire to assess gratitude, comprising items like “I have so much in my life to be thankful for”,

- the Indebtedness Scale-Revised (Maleki et al. 2005), to measure the degree to which individuals tend to feel indebted to other people, comprising items like “One should return favours from a friend as quickly as possible in order to preserve the friendship”.

Individuals who tended to adopt promotion focus, rather than prevention focus, were more likely to experience higher levels of gratitude. In contrast, individuals who tended to adopt a prevention focus were instead more likely to experience indebtedness. In a subsequent study, after individuals completed a task that primes a promotion focus, they also reported elevated levels of gratitude (Mathews & Shook, 2013). Presumably,

- when people who experience a promotion focus interact with someone else, they orient their attention to the gains they derived from this exchange, promoting gratitude,

- conversely, when people who experience a prevention focus interact with someone else, they orient their attention to the liabilities that emanate from this exchange, promoting a sense of indebtedness.