Parental style and behaviour

Introduction

Over many decades, researchers have posed a variety of theories to characterise the antecedents to narcissism. Many of these theories explicitly or implicitly underscore the role of parents. That is, these theories tend to assume that parental styles—the strategies that parents adopt to rear their children—may affect the likelihood or level of narcissism.

For example, according to a biopsychosocial-evolutionary theory, proposed by Millon (2004), some parents adopt a permissive style, in which they seldom, if ever, impose strict boundaries on the behaviour of their children. Instead, they dispense rewards, such as praise or attention, regardless of how their children behave. To attract these rewards, these children do not need to regulate their behaviour or develop their qualities. These children, therefore, do not develop the motivation or capacity to earn these rewards. Instead, these individuals feel they deserve rewards unconditionally, irrespective of their efforts or achievements, as if they are special. As they age, they maintain this belief that, for some reason, they deserve this praise and attention. If this praise or attention is not forthcoming, they feel affronted, often erupting with hostility and outrage.

Overvaluation versus devaluation

As research on this topic escalated, scholars recognised that diverse parenting styles may foster narcissism. These diverse parenting styles can largely be reduced to two main clusters: overvaluation and devaluation (see Miller et al., 2017; Löschner et al., 2025).

Overvaluation refers to circumstances in which parents exhibit both excessive and unconditional admiration towards their child. The child gradually develops the belief they are special, extraordinary, and better than everyone else (Brummelman et al., 2017), sometimes manifesting as narcissism. Yet, these children may also be exposed information, such as failures at school, that contradict this perception of themselves, eliciting an unpleasant sense of dissonance. To override this dissonance, these children seek respect and admiration from other people: a core feature of narcissism. This account may explain why parents who adopt a permissive style might encourage narcissism.

In contrast, devaluation refers to circumstances in which parents do not exhibit warmth towards the child. The child does not feel important or special. To override these feelings, the child may compensate to boost their self-esteem. They may, for example, bias their memories or interpretations of events to perceive themselves as capable or special. They also seek opportunities to validate this belief.

Meta-analyses on the association between narcissism and parents

Because a variety of studies have explored the relationship between narcissism and the practices of parents, Kılıçkaya et al. (2023) conducted a systematic review to explore this association methodically and comprehensively. The researchers entered narcissism and parenting, or minor variants to these terms, into a variety of scholarly databases, including Springer Link, PubMed, PsycNet, and ScienceDirect. The original set of 140 studies that emerged was reduced to 10 studies after publications that were written in other languages, conducted qualitative research, or conducted research that was not germane to this topic were excluded. All the studies were conducted at one time rather than longitudinally. The results uncovered some telling but sometimes cloudy patterns

First, most of the studies did reveal that permissive parenting—a style in which parents dispense rewards unconditionally rather than impose boundaries—is positively associated with narcissism. For example, as one study showed, when mothers tolerate most behaviours and perceive their children as special and deserving, these children are more likely to exhibit narcissism later in life (van Schie et al., 2020).

However, the association between narcissism and authoritarian parenting, in which parents impose strict rules but without justification or warmth, was more nuanced. For example

- according to some research, if mothers, fathers, or both adopt an authoritarian style, their children were likely to become narcissistic (Lootens, 2010; Ramsey et al., 1996).

- yet, other studies revealed that, if parents were cold—a manner that epitomises authoritarianism—their children were not as likely to develop narcissism (Barbin & Ocampo, 2017; Horton & Tritch, 2014),

- conceivably, a cold manner could diminish the likelihood that children perceive themselves as unconditionally special and worthy.

Most studies imply that children of authoritative parents—parents who justify the rules they set and exhibit warmth—are unlikely to develop narcissism.

The interdependency of parental overvaluation and coldness

To reiterate, as past research implies, individuals are more likely to exhibit narcissism later in life if their parents had been too permissive, displaying undue admiration of their children, or if their parents had been cold. However,

- parents who display this undue admiration, called overvaluation, tend to be warm—and this warmth diminishes the likelihood their children develop narcissism,

- similarly, parents who are cold seldom display undue, admiration, also decreasing the probability their children are narcissistic.

Accordingly, neither parental overvaluation not parental coldness will always foster narcissism in children. Instead, children will develop narcissism only in a circumstance that is not prevalent—the circumstance in which parents both admire their children inordinately but also exhibit coldness. Otway and Vignoles (2006) conducted a study that demonstrates this pattern. In this study, 120 participants, derived from a range of sources, completed a series of measures including

- the variant of the Narcissism Personality Inventory that comprises 40 items and the Hypersensitive Narcissism Scale to measure grandiose narcissism and vulnerable narcissism respectively,

- a set of 11 questions that assess the degree to which participants, when recalling their childhood, perceived their parents as cold, such as “When I was a child I sometimes wondered if my parents secretly felt spiteful toward me” and “When I was a child I did not receive much warmth or affection from my parents”,

- a set of four question that gauge the degree to which participants, when recalling their childhood, received undue admiration from their parents, called parental overvaluation, such as “When I was a child my parents believed I had exceptional talents and abilities” and “When I was a child my parents praised me for virtually everything I did”,

- the Experiences in Close Relationships-Revised (Brennan et al., 1998) to measure attachment style

When the data were subjected to structural equation modelling, parental overvaluation and parental coldness were both positively associated with grandiose narcissism and vulnerable narcissism, even after controlling the attachment style of participants. Admittedly, one of the associations—the relationship between parental overvaluation and vulnerable narcissism—was significant only at the 0.1 level. However, upon closer examination, Otway and Vignoles (2006) revealed some intriguing patterns:

- parental overvaluation was positively associated with some facets of grandiose narcissism—such as authority, exhibitionism, and superiority—only after controlling parental coldness,

- parental coldness was positively associated with one facet of grandiose narcissism—authority—only after controlling parental overvaluation.

This pattern is consistent with the notion that, in most families, parents who are cold do not admire their children inordinately. Because of this limited admiration, the children are not as likely to develop narcissism. Likewise, parents who do admire their children inordinately are often warm. Because of this warmth, the children are not as likely to develop narcissism. Yet, both parental overvaluation and parental coldness can foster narcissistic tendencies in children.

A model to explain how grandiose narcissism emanates from the behaviours of parents

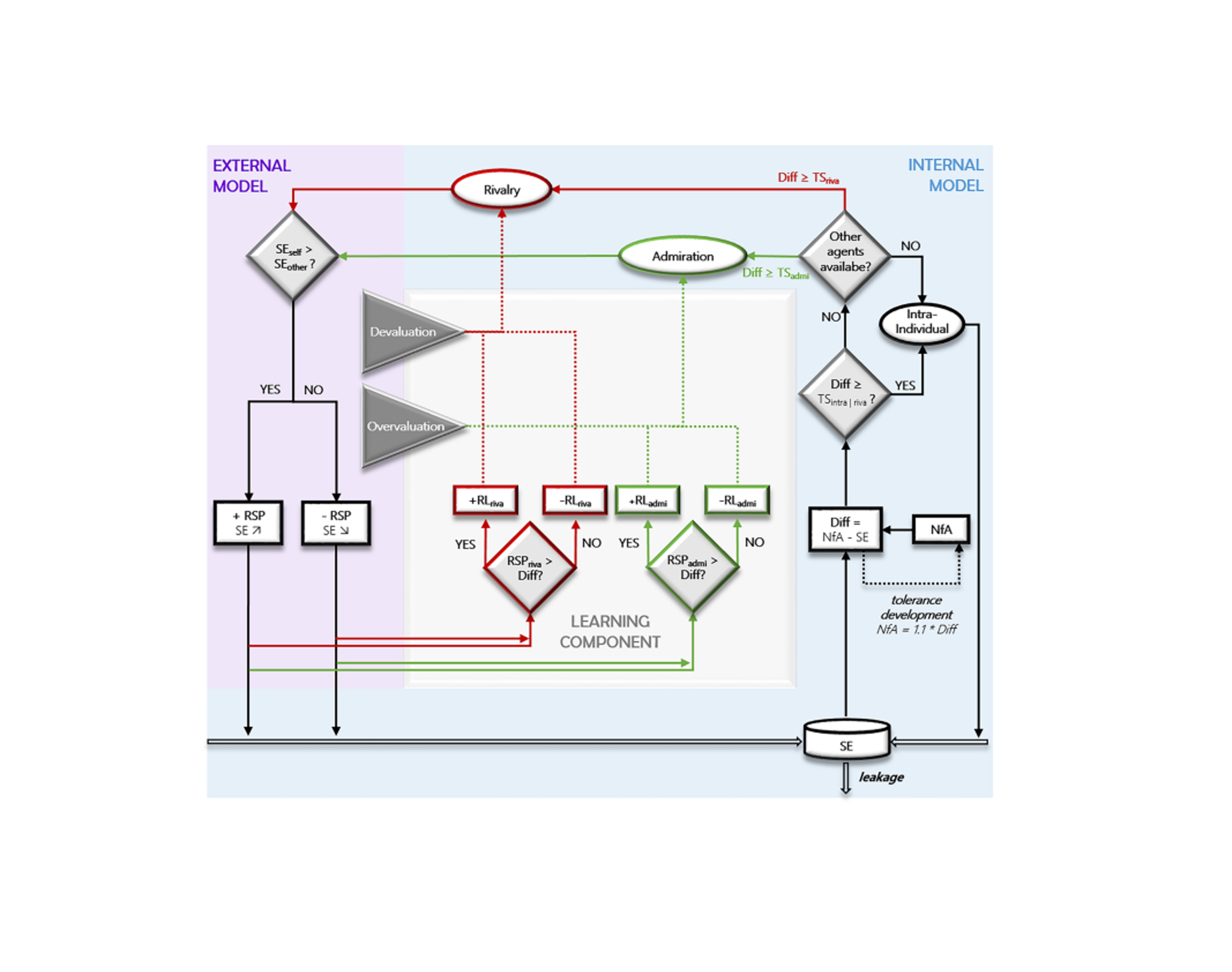

Although previous studies have explored the parenting styles that may foster narcissism, research has seldom characterised how the behaviour of parents and other events combine to affect the momentary behaviours of individuals that manifest as narcissism. To override this shortfall and thus to characterise the evolution of narcissistic behaviour in greater detail, Löschner et al. (2025) proposed and assessed a detailed computational model. The following schematic outlines this comprehensive model. Although seemingly complicated, the model can be reduced to a few key assumptions.

Here are the key assumptions of this model:

- The self-esteem of individuals tends to diminish over time, called leakage, unless other events or thoughts boost this self-esteem.

- If self-esteem drops below some threshold, individuals will experience the need to boost this self-esteem. This threshold is higher in people who experience a strong need to be admired.

- To boost self-esteem, people will first initiate what is called intra-individual regulation—biases in memories, appraisals, and other thoughts, such as an attempt to recall their achievements.

- But if self-esteem is appreciably below the threshold, people will also initiate what is called inter-individual regulation—in which they attempt to interact with other individuals to boost self-esteem. Specifically, these individuals will either seek validation, called an admiration strategy, or attempt to prevail over other people, called a rivalry strategy. The success of these strategies will shape self-esteem.

- If either the admiration strategy or rivalry strategy is successful—and self-esteem exceeds the threshold—these behaviours are reinforced and become more likely to be initiated in the future. That is, the threshold to activate these strategies diminishes.

- Over time, if the self-esteem of individuals tends to be high, the need to be admired also increases, called tolerance. In contrast, if their self-esteem tends to be low, this need to be admired decreases.

The behaviour of parents also shapes the parameters in this model. To illustrate, if parents exhibit overvaluation and hence often admire the child, the threshold to activate the admiration strategy diminishes. So, the child is more likely to initiate this strategy whenever their self-esteem is lower than desired. In contrast, if parents exhibit devaluation and hence seldom admire the child, the threshold to activate the rivalry strategy diminishes. So, the child is more likely to initiate this rivalry strategy whenever their self-esteem is lower than desired

In essence, this model integrates assumptions that were derived from six distinct theories or frameworks:

- self-discrepancy theory (Barnett et al., 2015)—such as the notion that a discrepancy between how individuals perceive themselves and the qualities they do not desire fosters narcissism,

- the hierometer theory—or the notion that which strategies individuals apply to boost their self-esteem, such as whether they should attempt to prevail in contests or defend themselves, depends on their self-esteem,

- the assumption that self-esteem in narcissistic people tends to decline over time, or leak, and that such individuals experience an addiction to overcome this leak and to boost their self-esteem (Baumeister & Vohs, 2001; Morf et al., 2001),

- the distinction between narcissistic admiration and narcissistic rivalry (Back et al., 2013),

- narcissism-imprinting parenting styles—or how parenting shapes narcissism (e.g., Brummelman et al., 2015),

- the principles of reinforcement learning.

In a series of three simulation studies, Löschner et al. (2025) applied this model to uncover some key insights about the dynamics and changes in narcissistic features over time. These simulation studies uncovered some vital insights:

- As thresholds to initiate admiration or rivalry diminish, the self-esteem of individuals oscillates more strongly over time. Accordingly, the tendency of these individuals to seek validation or to compete with other people tends to elicit pronounced fluctuations in self-esteem—typical of narcissistic individuals.

- Rivalry in particular amplified these fluctuations in self-esteem—and also tended to diminish self-esteem.

- Overvaluing parents tended to encourage more attempts in people to seek admiration and generally raised self-esteem, reminiscent of grandiose narcissism.

- Devaluing parents tended to encourage more attempts in people to seek rivalry or competition and generally diminished self-esteem, reminiscent of vulnerable narcissism.

Workplace conditions: Perceived overqualification and narcissism

Rationale

As some research indicates, when individuals perceive themselves as overqualified for a job, they may become more likely to demonstrate the signs of covert narcissism. Specifically, when individuals feel their role does not utilise their extensive capabilities—that is, when they experience a mismatch between their job and their abilities—they tend to experience psychological strain or unease for several reasons (e.g., see Debus et al., 2023). To illustrate, if individuals are unable to utilise their capabilities or qualifications

- they may feel a sense of isolation from peers who are able to utilise these capabilities or qualifications—and this isolation can elicit a sense of envy, stress, or strain,

- they may feel their circumstances are unfair or unjust (Mushtaq et al., 2025), and this sense of injustice can elicit frustrations and strain,

- they feel they may be forgoing vital opportunities—and the ensuing sense of loss can also evoke worry, stress, or strain.

This stress or strain—in concert with underutilised capabilities—could amplify any vestiges of covert narcissism that people may have developed (Mohamed et al., 2025). To illustrate,

- when individuals feel their capabilities are not utilised, they may feel their qualities and achievements are dismissed rather than valued; to override these feelings, they may feel the need to amplify their status—the cornerstone of narcissism,

- when individuals feel their capabilities are not utilised, they experience a disparity between their perception of themselves as capable and the treatment they receive; this disparity, coupled with stress, may elicit the belief they should be treated as special, analogous to entitlement,

- these semblances of narcissism, when combined with strain or stress, often manifest as covert narcissism—such as undue sensitivity to criticism and a tendency to undermine other people.

Evidence

Mohamed et al. (2025) published a study that corroborates the possibility that overqualification may foster or amplify covert narcissism. In this study, the participants were 446 nurses, working in various regions of Egypt, who completed an online survey. The survey comprised several validated scales:

- the perceived overqualification scale (Maynard et al., 2006), to assess the degree to which participants believe their capabilities and qualifications are not utilised in their job,

- the hypersensitive narcissism scale to gauge covert narcissism,

- the work alienation scale (Mottaz, 1981), to measure the extent to which individuals feel detached from their job,

- the role ambiguity scale (Rizzo et al., 1970), to assess the degree to which participants feel their job responsibilities or duties are hazy rather than unequivocal.

As hypothesised, perceived overqualification was positively associated with a feeling of alienation or detachment from work. Both covert narcissism and role ambiguity mediates this relationship (Mohamed et al., 2025). These findings imply that perceived overqualification fostered covert narcissism. Nevertheless, more rigorous designs, such as a randomised control trial, would be necessary to establish the direction of causality unambiguously. After all, covert narcissism could foster perceived overqualification rather than vice versa. Regardless, leaders should attempt to uncover opportunities that enable staff to utilise their capabilities and, thus, to diminish perceived overqualification.

Societal values: An egalitarian ideology

Rationale

Some workplaces, communities, and societies embrace egalitarian values. That is, in these settings, individuals tend to perceive everyone as equal in status. These individuals may recognise the strengths and drawbacks of all people or communities. To illustrate, these individuals may recognise that

- young people may not have developed the knowledge of their older counterparts—but may be more attuned to the latest trends or more receptive to change

- some communities may not be affluent but may be more collaborative, and so forth.

According to Piff (2014), these egalitarian values should diminish or prevent narcissism. When people adopt egalitarian values, they are not as likely to believe that some people are better, or higher in status, than other people. They do not, thus, feel the need to boost their status immediately—a need that epitomises narcissism.

Evidence

To assess this possibility, 137 adults, recruited from Amazon Mechanical Turk, were assigned to one of two conditions. To reinforce egalitarian values, some participants were instructed to list three benefits of regarding other people as equals. In the control condition, participants listed three activities they complete in a typical day. Participants then completed

- a measure of entitlement, comprising items like “I honestly feel I’m just more deserving than others””,

- the Narcissistic Personality Inventory to gauge narcissism

- a set of questions that assess social class, such as “I felt relatively wealthy compared to the other kids in my school” (Griskevicius et al., 2011).

As hypothesised, if participants had considered the benefits of egalitarian values, they were not as likely to demonstrate a sense of entitlement. They were also not as likely to exhibit narcissism, especially if they occupied a high social class (Piff, 2014).

Economic conditions and narcissism

Illustration

The economic conditions that individuals experience may also affect the likelihood they will develop the signs or manifestations of narcissism. To illustrate, in one study, conducted by Bianchi (2014), 1572 participants, representing a diversity of ages, completed several measures online including

- the Narcissism Personality Inventory, comprising 40 items, to assess grandiose narcissism,

- the Rosenberg measure of self-esteem.

To estimate the economic conditions these participants experienced during the ages of 18 to 25, researchers calculated the average national rate of unemployment during this time. As the data revealed, even after controlling age and self-esteem, the unemployment rate while individuals were aged 18 to 25 was inversely and strongly associated with narcissism (for concerns about this finding, see Fletcher, 2015; see Bianchi, 2015, for a counterargument).

Rationale

To explain these findings, Bianchi (2014) suggested that perhaps

- during the ages of 18 to 25, individuals establish beliefs about their relationship with society outside their family or community,

- if individuals experience moments of economic hardship during these times, they become more attuned to the need to preserve their resources, diminishing their propensity to embrace risks (Malmendier & Nagel, 2011),

- therefore, even after this hardship subsides, these individuals tend to be more cautious about their plans—a mindset that diverges from the grandiose aspirations of narcissistic people,

- likewise, if individuals experience moments of economic hardship during their emerging adulthood, they learn they may need to depend on other people and communities,

- this dependence instils an inclination in these individuals to accommodate other people and establish trusting networks (Park et al., 2014)—again an inclination that diverges from the conceited independence of their narcissistic counterparts.

Individualism versus collectivism

Rationale

As research has revealed, the culture in which people are reared, such as the values and priorities of their community, shape the personality these individuals develop (e.g., Markus & Kitayama, 1991). For example, in the United States, United Kingdom, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, and Europe, nations that are often labelled as Western, communities often value personal achievement, independence, and autonomy—called individualism. These individuals orient attention more to their unique characteristics than to the groups or communities to which they belong.

In contrast, in many Asian countries, nations that are often labelled as Eastern, communities tend to value conformity to traditional norms and social obligations as well as harmony with other members—called collectivism. These individuals orient attention more to their relationships or communities instead of their unique qualities.

Arguably, whether individuals belong to an individualist culture or collectivist culture may affect the incidence of narcissism. Individuals who exhibit individual narcissism are motivated to boost their personal status, rank, or significance as rapidly as possible, reminiscent of strident individualism. Thus, individualism may foster grandiose narcissism, and perhaps vulnerable narcissism, but not necessarily collective narcissism.

Illustration: Comparison between West Germans and East Germans

To explore these possibilities, Vater et al. (2018) examined the narcissism of German individuals across multiple generations. Until 1945, West Germany and East Germany shared a common set of values, norms, and practices. Between 1945 and 1989, West Germany retained a capitalist ideology and maintained an individualist culture. In contrast, East Germany adopted a community ideology and gradually espoused a more collectivist culture. However, in 1989, after the Berlin Wall collapsed, the culture in West Germany and East Germany gradually converged. According, the researchers hypothesised that

- West Germans should be more likely than East Germans to exhibit the signs of narcissism,

- however, if individuals were primarily raised after the Berlin Wall collapsed, this difference between West Germans and East Germans on narcissism should dissipate.

In this study, over 1000 participants, who had been reared in either West Germany or East Germany during their childhood and adolescence, completed a series of measures comprising

- the Narcissistic Personality Inventory—a comprehensive measure of grandiose narcissism,

- the Pathological Narcissism Inventory—a scale that assesses several facets of both grandiose narcissism and vulnerable narcissism,

- the Rosenberg self-esteem scale.

As the data revealed, in the oldest participants, who were adults when the Berlin wall collapsed,

- grandiose narcissism, as gauged by the Narcissistic Personality Inventory, was higher in West Germans than East Germans,

- hence, consistent with the hypotheses, individuals raised in East Germany before the Berlin Wall collapsed were not as likely to exhibit grandiose narcissism (Vater et al., 2018).

In participants who were children, aged between 6 and 18, when the Berlin wall collapsed

- three facets of grandiose narcissism and one facet of vulnerable narcissism—hiding the self or the tendency to conceal personal shortcomings—were higher in West Germans than East Germans,

- this discrepancy between West Germans and East Germans on vulnerable narcissism might have evaporated in the oldest participants because this personality trait tends to diminish with age,

- self-esteem, however, was lower in West Germans than East Germans.

In the youngest participants, who were under 5 when the Berlin wall collapsed, consistent with the hypotheses, neither narcissism nor self-esteem depended on whether these individuals were reared in West Germany or East Germany.

Disparities between grandiose narcissism and vulnerable narcissism

To reiterate, Vater et al. (2018) revealed that grandiose narcissism, and perhaps vulnerable narcissism, may be more prevalent in West Germany than East Germany. However, only one facet of vulnerable narcissism was more pronounced in West Germany. Consequently, the relationship between vulnerable narcissism and culture warrants more research.

Indeed, as Jauk et al. (2021) argued, a more collectivist mindset could instead amplify vulnerable narcissism. Specifically, in collectivist nations, such as Japan, individuals are more inclined to define themselves by their relationships and communities, originally called an interdependent self-construal (Singelis, 1994). In these communities, individuals strive to be accepted and trusted. Therefore, if these individuals are preoccupied with status—a hallmark of narcissism—they may be especially sensitive to cues that indicate they are not accepted or trusted. This sensitivity to rejection is a defining feature of vulnerable narcissism.

In contrast, in more individualist nations, such as Western European countries, individuals are more inclined to define themselves by their personal characteristics, originally called an independent self-construal (Singelis, 1994). In these communities, individuals strive to be perceived as competent, powerful, independent, and unique (e.g., Hannover et al., 2006). Accordingly, if these individuals are narcissistic and thus preoccupied with status, they are more inclined to inflate their capabilities, achievements, or influence: the cornerstone of grandiose narcissism. In short, narcissism should manifest as vulnerable in collectivist nations and as grandiose in individualist nations.

To confirm these hypotheses, Jauk et al. (2021) published a study in which 280 Japanese participants and 258 German participants completed on online survey that included

- a very short version of the Narcissistic Personality Inventory to measure grandiose narcissism,

- two scales to measure vulnerable narcissism: the Hypersensitive Narcissism Scale and the Maladaptive Covert Narcissism Scale (see Cheek et al., 2013),

- the Self-Construal Scale (Singelis, 1994) to gauge both an interdependent self-construal (e.g., “Even when I strongly disagree with group members, I avoid an argument”) and an independent self-construal (“I enjoy being unique and different from others in many respects”),

- as well as measures of the five personality traits, intrapersonal maladjustment (Derogatis & Melisaratos, 1983), and interpersonal maladjustment (Horowitz et al., 2000).

In general, the findings were consistent with the hypotheses (Jauk et al., 2021). For example

- vulnerable narcissism was significantly more prevalent in Japan than in Germany, whereas grandiose narcissism was marginally, but not significantly, more prevalent in Germany than in Japan,

- after controlling personality, vulnerable narcissism was positively associated with an interdependent self-construal and grandiose narcissism was positively associated with an independent self-construal.

Determinants of collective narcissism: The spiritual formidability of collectives

Rationale

According to the formidability representation hypothesis, to decide whether to flee, fight, or negotiate, when individuals are confronted with a rival, they need to decide, as rapidly as possible, whether their resources, assets, and liabilities are superior. That is, they need to gauge whether they are formidable, compared to rivals, in their resources, skills, and technologies.

To assess their formidability, not only do these collectives consider their materials and technology but also their belief in the cause or values of this community, called spiritual formidability. That is, if individuals experience spiritual formidability, they feel a sense of conviction in the cause of this collective and commit to pursue this cause (Gómez et al., 2017; Gómez, Vázquez, et al., 2023). They may fight to pursue this cause, even if they do not possess the material or technological advantages of their rivals.

As Chinchilla and Gomez (2025) proposed and revealed, this spiritual formidability—or conviction in the cause or values of this collective—can promote collective narcissism. That is,

- when individuals perceive the cause or morality of their collective as superior, they feel attached to this collective,

- yet, without tangible evidence to demonstrate this superiority, they strive to confirm the supremacy of this collective,

- for example, they may bias their thoughts towards the favourable qualities of this collective, often manifesting as collective narcissism.

Evidence

To illustrate, in one study, inmates first identified a gang to which they belonged. Next, these inmates completed a series of measures, under supervision:

- First, to measure spiritual formidability, these participants dragged a slider that increased the size and muscularity of a human body that appeared on a screen. The participants used this slider to represent the spiritual formidability of their collective (Gómez et al., 2017).

- Next, participants completed a measure of collective narcissism (see Golec de Zavala et al., 2013), comprising items like “If my gang had a major influence on the world, the world would be a much better place”.

- Finally, participants indicated the extent to which they would be willing to sacrifice their personal interests to support this collective, epitomised by items like “If it was necessary to defend my group, I would be willing to move to a prison further away from my family”.

As hypothesised, if participants regarded their gang as spiritually formidable, they were more likely to report collective narcissism (Chinchilla & Gomez, 2025). This collective narcissism also predicted the willingness of individuals to sacrifice their personal interests to support this collective.

Subsequent studies extended this finding. For example, in one study of 457 Spanish individuals, spiritual formidability was manipulated. That is,

- in one condition, to enhance spiritual formidability, participants were informed that most Spaniards had selected the second most muscular body to represent the spiritual formidability of Spain

- in the control condition, participants did not receive this information.

If informed that most Spaniards perceived their nation as spiritually formidable, these participants were more likely to report collective narcissism about their nation. These individuals were also more willing to sacrifice their personal interests to support their country (Chinchilla & Gomez, 2025).