Overview

Researchers have designed a variety of instruments to measure levels of narcissism. For example,

- some instruments assess the degree to which individuals demonstrate grandiose narcissism—or the tendency of some people to exaggerate their achievements and capabilities as well as to crave attention or respect,

- other instruments assess the extent to which individuals demonstrate vulnerable narcissism—or the tendency of some people not only to dismiss criticism but to exhibit contempt or rage towards anyone who delivers this criticism as well as to depict themselves as victims of injustice,

- some instruments assess distinct facets or features of narcissism, such as need for admiration, entitlement, and exhibitionism.

Grandiose or overt narcissism

A typical example

Many researchers have developed scales that measure grandiose narcissism. To illustrate, Foster et al. (2015) designed and validated the Grandiose Narcissism Scale, comprising 33 items. These items measure overall grandiose narcissism as well as several subscales:

- authority or the preference to be designated as an authority, such as “I am a natural born leader” or “I lead rather than follow”,

- self-sufficiency or a preference to complete tasks alone, such as “I do not like to depend on other people to do things”,

- superiority or a feeling they are better than other people, such as “I am more talented than most other people”,

- vanity or an obsession with physical appearance, such as “My looks are important to me”,

- exhibitionism or a need to attract the attention of people, such as “I do things that get people to notice me”,

- entitlement or the sense they deserve special treatment, such as “I expect to be treated better than average”, and

- a willingness to exploit other people, such as “I’m willing to manipulate others to get what I want”.

As evidence of validity, overall grandiose narcissism, derived from combining these subscales, was positively associated with extraversion, a feeling of agency, and aggression as well as negatively associated with agreeableness and empathy.

The Narcissistic Personality Inventory

In essence, the Grandiose Narcissism Scale is a shortened version of a previous instrument, called the Narcissistic Personality Inventory, briefly outlined by Raskin and Hall (1979). Indeed, many, if not most, measures of grandiose narcissism emanated from this seminal Narcissistic Personality Inventory or NPI. Unlike the Grandiose Narcissism Scale, the Narcissistic Personality Inventory comprises 223 items. Each of these items comprise two statements, only one of which epitomises narcissism, such as

- I really like to be the centre of attention

- It makes me uncomfortable to be the centre of attention.

Subsequently, one of the developers of this Narcissistic Personality Inventory, Robert Raskin, and another collaborator, Howard Terry, designed a shortened version of this inventory, comprising only 40 pairs of statements (Raskin & Terry, 1988). This version is called the NPI-40 and also gauges seven facets, such as authority, self-sufficiency, superiority, vanity, exhibitionism, entitlement, and the inclination to exploit people (for a German version, see Schütz et al., 2004; for a Polish version comprising 34 items, see Bazińska & Drat-Ruszczak, 2000).

Other shortened versions

Other researchers have developed even shorter versions of the Narcissistic Personality Inventory. Ames et al. (2006), for example, devised a variant of the Narcissistic Personality Inventory that comprises only 16 items. Unlike other variants, this shorter variant, called the NPI-16, corresponds to only facet or factor. For each item, participants choose which of two statements describe their character, such as

- “I like to be the centre of attention” versus “I prefer to blend in with the crowd”,

- “I am an extraordinary person” versus “I am much like everybody else”,

- “I always know what I am doing” versus “Sometimes I am not sure of what I am doing”,

- “I like having authority over people” versus “I don’t mind following orders”.

The NPI-16 and NPI-40 generate similar correlations to other measures. For example,

- they both are positively and moderately associated with openness-to experience, extraversion, and self-esteem

- they both are negatively and moderately associated agreeableness and neuroticism.

A shortened variant with three sub-scales

Gentile et al. (2013) later developed another shortened version, comprising only 13 items, that also generates three subscales. This version appears to be valid, correlating with the same traits as did the NPI-16 and NPI-40—such as diminished levels of agreeableness, psychopathy, attention seeking, dominance, coldness, and aggression in response to electric shocks. The three subscales were

- leadership and authority, such as “People always seem to recognise my authority”,

- grandiose exhibitionism, such as “I like to look at my body”, and

- entitlement and inclination to exploit people, such as “I find it easy to manipulate people”.

The first two subscales were significantly associated with traits that epitomise grandiose narcissism. The third subscale, around entitlement and exploitation, was significantly associated with antagonism—a tendency that is common in both grandiose narcissism and vulnerable narcissism.

Vulnerable or covert narcissism

The hypersensitive narcissism scale

To measure vulnerable narcissism, many researchers deploy the hypersensitive narcissism scale (Hendin & Cheek, 1997), developed at Wellesley College in Massuchusetts. This scale comprises the following 10 items:

- I can become entirely absorbed in thinking about my personal affairs, my health, my cares or my relations to others.

- My feelings are easily hurt by ridicule or by the slighting remarks of others.

- When I enter a room, I often become self-conscious and feel that the eyes of others are upon me.

- I dislike sharing the credit of an achievement with others.

- I dislike being with a group unless I know that I am appreciated by at least one of those present.

- I feel that I am temperamentally different from most people.

- I often interpret the remarks of others in a personal way.

- I easily become wrapped up in my own interests and forget the existence of others.

- I feel that I have enough on my hands without worrying about other people’s troubles.

- I am secretly ‘‘put out’’ when other people come to me with their troubles, asking me for my time and sympathy.

As evidence of discriminant validity, this measure hardly correlates at all with the Narcissistic Personality Inventory—a measure of grandiose narcissism. Furthermore, as evidence of validity, hypersensitive narcissism is positively associated with neuroticism but inversely associated with extraversion, agreeableness, and openness to experience.ay not acknowledge or even be aware of this tendency. Consequently, the items did not refer to humility explicitly. In addition, some of the items depicted characteristics, such as “I feel that I do not deserve more respect than other people”, that people who are not humble would be unwilling to concede, even if they wanted to depict themselves favourably.

The two-factor model: egocentrism versus oversensitivity

As some research indicates, the hypersensitive narcissism scale, although initially assumed to measure only a single facet, may gauge two distinct facets instead. To illustrate, Fossati et al. (2009) administered this instrument to 366 psychiatric outpatients and 385 other participants.

As Procrustes analyses revealed, in both the clinical and nonclinical samples, responses to the hypersensitive narcissism scale generate two factors. The first factor, called egocentrism, revolves around a tendency of some individuals to be concerned only about their own goals, disregarding the needs of other people (Fossati et al., 2009). Items that assess this factor or facet include

- I dislike sharing the credit of an achievement with others.

- I feel that I have enough on my hands without worrying about other people’s troubles.

- I am secretly ”put out” when other people come to me with their troubles, asking me for my time and sympathy.

- I easily become wrapped up in my own interests and forget the existence of others.

The second factor, called oversensitivity, revolves around the tendency of some people to feel hurt, offended, or alienated easily as well as anxious in social circumstances (Fossati et al., 2009). Items that assess this factor or facet include

- My feelings are easily hurt by ridicule or by the slighting remarks of others.

- When I enter a room, I often become self-conscious and feel that the eyes of others are upon me.

- I often interpret the remarks of others in a personal way.

- I dislike being with a group unless I know that I am appreciated by at least one of those present.

Another two-factor model: the Vulnerable Isolation and Enmity Questionnaire

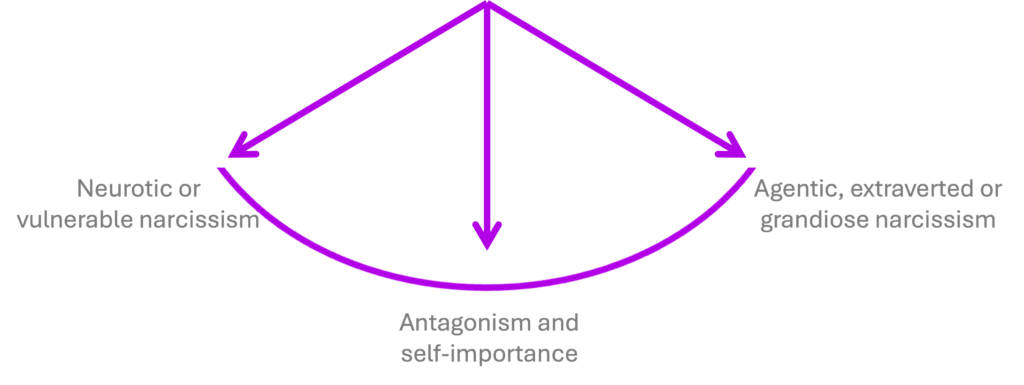

Rogoza et al. (2022) designed and validated another measure of vulnerable narcissism that comprises two subscales: isolation versus enmity. This measure is predicated on the narcissism spectrum model (Krizan & Herlache, 2018) and the trifurcated model of narcissism (Miller et al., 2016; Weiss et al., 2019). According to these models,

- a central feature of narcissism is antagonism, in which individuals perceive themselves as more important than anyone else and thus feel entitled and inclined to exploit other people,

- however, when this antagonism is combined with extraversion—that is, a proactive, demonstrative, and dominating personality style—individuals tend to exhibit grandiose narcissism,

- in contrast, when this antagonism is combined with neuroticism—that is, an apprehensive, avoidant, and anxious personality trait—individuals tend to exhibit vulnerable narcissism.

This model implies that vulnerable narcissism may entail two distinct facets: enmity and isolation. Specifically, the antagonistic features of vulnerable narcissism may shape the perception that other people are untrustworthy rivals who need to be defeated, called enmity. The neurotic features of vulnerable narcissism may compel people to shun relationships, primarily to prevent criticism and to protect their self-esteem, called isolation.

To construct these two subscales—enmity and isolation— Rogoza et al. (2022) designed a scale that comprises 24 items. Twelve items measure four facets of enmity:

- envy of other people, such as “I only feel good when others turn out to be worse than me”,

- paranoia in which individuals feel they may be harmed by other people, such as “When people whisper, I feel that they are plotting against me”,

- projection in which individuals perceive other people as hostile, such as “People are aggressive towards me for no reason”,

- spitefulness in which individuals are vengeful, such as “I would not mind if someone who treated me badly got hurt”.

Similarly, twelve items measure four facets of isolation:

- hiding from relationships to prevent hurt, the self, such as “I hang back so that others can’t hurt me”,

- inhibition of expression to prevent ridicule, such as “Usually I’m quiet because I do not want to expose myself to ridicule”,

- rumination about previous failures or shortfalls, such as “I often get tired of thinking about how I am perceived”,

- passive entitlement or suffering when they realise they are not treated as special, such as “I suffer because of the fact that others do not try to understand what I need”.

Hence, this scale comprises eight facets, each of which correspond to three items. To establish the validity of this Vulnerable Isolation and Enmity Questionnaire, Rogoza et al. (2022) administered the instrument as well as other measures of narcissism, self-esteem, personality, and popularity with classmates to five distinct samples, including students and members of the public. In general, the findings corroborated the validity of this questionnaire. For example

- both enmity and isolation were highly correlated with other measures of vulnerable narcissism, such as the Hypersensitivity Narcissism Scale, the Vulnerability Narcissism Scale, and the vulnerability subscale of the Pathological Narcissism Inventory—with correlations exceeding 0.5,

- conversely, both enmity and isolation were only modestly correlated with other measures of grandiose narcissism, such as the Narcissistic Grandiosity Scale—with correlations lower than 0.3,

- furthermore, both enmity and isolation were inversely associated with self-esteem,

- finally, both enmity and isolation positively associated with a measure of neuroticism and negatively associated with a measure of extraversion.

Rogoza et al. (2022) also validated a shortened version, in which each facet corresponded to one item. Further research may be necessary, however, to validate the distinction between the two subscales and the eight facets.

Narcissism admiration and rivalry

Whereas some instruments measure either grandiose or vulnerable narcissism, other instruments measure both of these facets. One possible example is the Narcissistic Admiration and Rivalry Questionnaire, developed by Back et al. (2013; for a Polish version, see Rogoza et al., 2016). Specifically, according to Back et al.,

- to boost their status, some individuals apply strategies that attract respect and admiration, such as inflate their achievements, sometimes called self-enhancement,

- in contrast, to maintain their status, other individuals apply strategies that denigrate other people—such as people who criticise their behaviour—sometimes called self-protection.

To represent these two strategies, respectively called narcissistic admiration and narcissistic rivalry, Back et al. developed an instrument that comprises 18 items (for a shorter version, see Leckelt et al., 2018). Narcissistic admiration manifests in motives, thoughts, and behaviours and thus comprises three distinct facets:

- the motive to be unique, such as “Being a very special person gives me a lot of strength”,

- thoughts around grandiosity, such as “I deserve to be seen as a great personality”, and

- charming behaviour, such as “I manage to be the centre of attention with my outstanding contributions”.

Similarly, narcissistic rivalry also manifests in motives, thoughts, and behaviours and comprises three distinct facets, including

- the motive to achieve supremacy and even humiliate other people, such as “I want my rivals to fail”,

- thoughts about the shortcomings of other individuals, such as “Most people are somehow losers”, and

- aggressive behaviour, such as “I react annoyed if another person is at the centre of events”.

Narcissistic admiration and rivalry were positively associated with each other. To explain this association, one possibility is that narcissistic admiration may precede narcissism rivalry. Specifically, individuals who exhibit narcissistic admiration may, after they attract some respect, typically by inflating their qualities or contributions, feel this admiration is fragile. To maintain this status, these individuals may then feel compelled to defend their rank in a competitive, hostile social environment, manifesting as narcissistic rivalry.

As Back et al. (2013) also revealed, narcissistic admiration and narcissistic rivalry were both associated with the big five personality traits. Specifically, narcissistic admiration was positively associated with extraversion and openness to experience as well as inversely associated with neuroticism. In contrast, narcissistic rivalry was positively related to neuroticism and inversely related to agreeableness and conscientiousness. Furthermore, narcissistic admiration and narcissistic rivalry were positively and negatively associated with self-esteem respectively. Finally, both dimensions were positively associated with a measure of psychopathy but only narcissistic rivalry was positively associated with a measure of Machiavellianism.

A further study, also conducted by Back et al. (2013), explored the association between these narcissistic dimensions and relationships. Narcissistic rivalry was inversely related to empathy, trust, forgiveness, and gratitude in relationships—as well as a tendency to seek revenge in response to transgressions. In contrast, narcissistic admiration was not as strongly related to these measures.

The strategies that correspond to narcissistic admiration and rivalry

According to Back et al. (2013), to boost their status, individuals who report narcissistic admiration may apply a diversity of strategies, often designed to achieve some gain or improvement. In contrast, to maintain their status, individuals who report narcissistic rivalry apply fewer strategies, primarily revolving around their attempts to outperform and undermine other people.

Zeigler‐Hill et al. (2019) conducted a study that explores these strategies explicitly. For example, in one study, 1219 participants completed the Narcissistic Admiration and Rivalry Questionnaire as well as the Fundamental Social Motives Inventory (Neel et al., 2016). This inventory gauges the degree to which individuals prioritise six motives in social settings, including

- status seeking (e.g., “It’s important to me that others respect my rank or position”),

- affiliation (e.g., “Being part of a group is important to me”),

- kin care (e.g., “Caring for family members is important to me”)

- self-protection (e.g., “I think a lot about how to stay away from dangerous people”),

- disease avoidance (e.g., “I avoid places and people that might carry diseases”),

- mate seeking (e.g., “I spend a lot of time thinking about ways to meet possible dating partners”),

- mate retention (e.g., “It is important to me that my partner is sexually loyal to me”).

As the data revealed

- status seeking was more strongly associated with narcissistic admiration than with narcissistic rivalry,

- narcissistic admiration was positively associated with all other motives as well, except disease avoidance or mate retention,

- besides status seeking, narcissistic rivalry was positively associated only with mate-seeking, and mate-retention and inversely associated with kin care.

These findings indicate that narcissistic admiration, when compared to narcissistic rivalry, may coincide with a more extensive range of motives and a more pronounced motivation to seek status. In a second study, 760 participants completed

- the Narcissistic Admiration and Rivalry Questionnaire,

- the Dominance-Prestige Scales (Cheng et al., 2010) to assess the degree to which individuals strive to demonstrate their dominance (e.g., “I am willing to use aggressive tactics to get my way”) or prestige (e.g., “I am considered an expert on some matters by others”).

As multiple regression analyses revealed, both narcissistic admiration and narcissistic rivalry were positively associated with the inclination of individuals to demonstrate their dominance. In contrast, narcissistic admiration was positively associated, but narcissistic rivalry was negatively associated, with the inclination of individuals to seek prestige. Accordingly, if people exhibit narcissistic admiration, they adopt a competitive mindset as well as attempt to display their competence to boost their status. In contrast, if people exhibit narcissistic rivalry, they adopt a competitive mindset to maintain their status but are not especially motivated to display their competence (Zeigler‐Hill et al., 2019).

Grandiose versus vulnerable narcissism

Originally, both narcissistic admiration and narcissistic rivalry were deemed as facets of grandiose narcissism (Back et al., 2013; for a similar assumption, see Biolik, 2025). Maples et al. (2025), however, revealed that narcissistic admiration tends to coincide with grandiose narcissism and narcissistic rivalry tends to coincide with vulnerable narcissism. This study administered a series of questionnaires to three samples of participants. These questionnaires included

- the Narcissistic Admiration and Rivalry Questionnaire,

- the Narcissism Grandiosity Scale to assess grandiose narcissism,

- the Hypersensitive Narcissism Scale to assess vulnerable narcissism,

- the Pathological Narcissism Inventory—to gauge more pathological or extreme signs of narcissism,

- other scales including measures of personality, aggression, and self-esteem.

The data were subjected to a series of techniques, including latent profile analysis and structural equation modelling. In essence, the findings revealed that

- narcissistic admiration tends to coincide with measures of grandiose narcissism, such as the Narcissism Grandiosity Scale, as well as high extraversion and low neuroticism,

- narcissistic rivalry tends to coincide with measures of vulnerable narcissism, such as the Hypersensitive Narcissism Scale as well as high neuroticism, high aggression, and low self-esteem.

The unified model

One concern with previous models is the degree to which they apply to multiple nations and cultures. To address this matter, Sivanathan et al. (2021, 2023, 2025) proposed the unified model of narcissism. This model recognises that several characteristics, such as a sense of entitlement and the ensuing antagonism towards other people, are common to both grandiose and vulnerable narcissism. However, grandiose and vulnerable narcissism also comprise unique features that are common across cultures. Specifically, the universal features of grandiose narcissism are

- leadership—a facet that entails a sense of superiority and a tendency to overestimate personal qualities and contributions,

- vanity—or an undue emphasis on physical appearance or other superficial qualities.

In contrast, the universal features of vulnerable narcissism are

- contingent self-esteem—in which individuals seek validation from other people excessively and derive their worth from this validation,

- hiding personal needs, including shame or fear their personal thoughts or feelings may be rejected,

- grandiose fantasy—or a preoccupation with power, achievement, and admiration.

According to Sivanathan et al. (2025), all five facets contribute to a sense of entitlement. To illustrate

- because of their sense of leadership, narcissistic individuals feel they should be entitled to be granted authority over other people,

- because of their vanity, narcissistic individuals feel they are entitled to receive admiration,

- because their self-esteem is contingent upon validation, narcissistic individuals feel should be entitled to receive praise,

- because they hide personal needs, narcissistic individuals feel they should be admired because of the thoughts or feelings they express,

- because of grandiose fantasy, narcissistic individuals feel they should be respected because of their imagined success or power.

To represent these five facets, Sivanathan et al. (2025) developed a shortened version of their previous unified narcissism scale. The scale comprises 15 items, 3 items representing contingent self-esteem, leadership, grandiose fantasy, vanity, and hiding personal needs in order.

- [Contingent self-esteem] When others don’t notice me, I start to feel worthless

- When people don’t notice me, I start to feel bad about myself.

- I spend a lot of time thinking about what other people think of me.

- [Leadership] As a leader, I know what is best for my team.

- If I became a leader, I would be the best.

- I have better leadership skills than other people.

- [Grandiose Fantasy] I want to amount to something in the eyes of the world.

- I often fantasize about being admired and respected.

- I fantasize about being a hero.

- [Vanity] I think I turn heads when I walk down the street.

- I am exceptionally good looking.

- I enjoy taking photos of myself because I look so good.

- [Hiding One’s Needs] It’s hard to show others the weaknesses I feel inside.

- I would feel so ashamed if someone found out all parts of me.

- I become a different person when I am with others for fear of disapproval.

Confirmatory factor analysis validated these sub-scales in four nations: United States, China, Sri Lanka, and Australia. Grandiose narcissism was lowest in Australia, potentially because Australians tend to be especially resistant to hierarchy.

The five-factor model of narcissism

Some measures and taxonomies of narcissism emanate from the five-factor model of personality. According to the five-factor model of personality, the entire gamut of personality characteristics can be reduced to one of five key traits: extraversion, neuroticism, conscientiousness, agreeableness, and openness to experience. If this model is accurate, each facet of neuroticism should also correspond to one of these five traits (Miller et al., 2016).

Overview of the five-factor model

The five traits were initially derived from attempts to categorise the adjectives that are commonly used to describe individuals but later verified and refined using factor analyses, a statistical technique that is conducted to identify sets of correlated dimensions. Each of these five traits tend to comprise six distinct but underlying facets (Costa & McCrae, 1992):

- To illustrate, individuals who exhibit extraversion are gregarious, assertive, warm, positive, and active, as well as seek excitement.

- The six facets that underpin neuroticism, as defined by Costa and McCrae (1992), relate to the extent to which individuals exhibit anxiety, depression, and hostility as well as feel self-conscious, act impulsively, and experience a sense of vulnerability, unable to accommodate aversive events.

- The six facets that underpin agreeableness are trust in other individuals, straightforward and honest communication, altruistic and cooperative behaviour, compliance rather than defiance, modesty, as well as tender, sympathetic attitudes.

- The six facets that correspond to conscientiousness relate to the degree to which individuals are competent, methodical–preferring order and structure, dutiful, motivated to achieve goals, disciplined, and deliberate or considered.

- Finally, openness to experience relates the extent to which individuals are open to fantasies, aesthetics, feelings, as well as novel actions, ideas, and values (Costa & McCrae, 1992). Open individuals prefer novel, intense, diverse, and complex experiences (McCrae, 1996). In contrast, closed individuals prefer familiar tasks and standardized routines (McCrae, 1996).

The original measure of the five-factor model of narcissism: the five-factor narcissism inventory

These facets of the five personality traits have informed several measures of narcissism. For example, Glover et al. (2012) constructed a measure that is predicated on the assumption that narcissism corresponds to maladaptive variants of these facets. Specifically, these researchers identified 15 facets of the five-factor model that can be adapted to characterise features of narcissism.

To illustrate, consider one facet of neuroticism, called angry hostility. Individuals who exhibit narcissism might display a maladaptive variant of this facet, in which they explode in anger whenever they are criticised or slighted. The researchers then constructed 30 questions to characterise this maladaptive variant of angry hostility, called reactive anger.

Similarly, the researchers uncovered 14 other maladaptive variants of the five-factor model that may characterise narcissism—and then wrote about 30 items to measure each facet. These facets, coupled with a sample item, include

- reactive anger (e.g., “I have, at times, gone into a rage when not treated rightly”),

- shame (e.g., “When I realize I have failed at something, I feel humiliated”),

- indifference (e.g., “Others’ opinions of me are of little concern to me”),

- need for admiration (e.g., “I want so much to be admired by others”),

- exhibitionism (e.g., “I enjoy being in front of an audience or big crowd”),

- thrill-seeking (e.g., “I like to have new and exciting experiences, even if they are a little frightening”),

- authoritative (e.g., “I tend to take charge of most situations”),

- grandiose fantasies (e.g., “I daydream about someday becoming famous”),

- cynicism or distrust (e.g., “You have to look out for your own interests because no one else will”),

- manipulativeness (e.g., “I will mislead people if I think it is necessary”),

- exploitative (e.g., “If people are ignorant enough to let me take advantage of them, so be it”),

- entitlement (e.g., “I believe I am entitled to special accommodations”)

- arrogance (e.g., “I only associate with people of my calibre”),

- lack of empathy (e.g., “I’m not big on feelings of sympathy”),

- acclaim-seeking (e.g., “I have devoted my life to success”).

Each subscale roughly overlaps with one of the five personality traits. To illustrate,

- high levels of neuroticism—one of the five personality traits—correspond to four of the subscales: reactive anger, shame, indifference, and need for admiration,

- high levels of extraversion correspond to three subscales: authoritativeness, exhibitionism, and thrill seeking,

- high levels of openness correspond to one subscale: grandiose fantasies,

- low levels of agreeableness correspond to six subscales: arrogance, cynicism or distrust, entitlement, exploitative-ness, limited empathy, and manipulativeness,

- high levels of conscientiousness correspond to one subscale: acclaim seeking.

To validate this measure, 333 undergraduate psychology students, enrolled at the University of Kentucky, completed this inventory of 390 items as well as

- the NEO personality inventory-revised to gauge the five personality traits,

- the Narcissistic Personality Inventory to measure grandiose narcissism,

- the Hypersensitivity Narcissism Scale to measure vulnerable narcissism,

- the Pathological Narcissism Inventory to assess more pathological levels of narcissism,

- a validity scale to verify that participants were answering the questions carefully, such as “I have used computers in the past two years”,

- the Millon Clinical Multiaxial Inventory–III to assess personality disorders (Millon et al., 2009),

- as well as other measures of personality disorders (e.g., Bagby & Farvolden, 2004; Simms & Clark, 2006).

The findings attest to the validity of this scale. For example,

- the 15 facets of this five-factor narcissism inventory were highly correlated with the corresponding facets of the NEO personality inventory-revised,

- one exception is that grandiose narcissism, a facet of the five-factor narcissism inventory, was not significantly associated with the corresponding openness to fantasy facet, contrary to hypotheses,

- the 15 facets were only modestly associated with each other, consistent with the assumption that narcissism is not homogenous but comprises a set of distinct maladaptive tendencies (Widiger & Trull, 2007),

- the facets were associated with other measures of narcissism, as predicted.

Additional research has also validated this instrument (e.g., Miller et al., 2013; for a shorter variant, see Sherman et al., 2015). Each subscale also coincides with either grandiose narcissism or vulnerable narcissism. Researchers can, therefore, derive a score for grandiose narcissism and vulnerable narcissism from this scale.

Agentic, antagonistic, and neurotic narcissism

As Miller et al. (2016) subsequently revealed, this instrument primarily represents high or low levels of three personality traits in particular:

- elevated levels of extraversion, such as authoritativeness,

- very low levels of agreeableness, such as arrogance.

- elevated levels of neuroticism, such as reactive anger, and

Therefore, although derived from the five-factor model of personality, these findings indicate that narcissism may comprise three key factors, often called the three-factor model or trifurcated model of narcissism. After more detailed analyses and research, the definition of these three factors has gradually evolved (Miller et al., 2021; Weiss et al., 2019). Specifically, these three factors are usually labelled

- agentic narcissism, representing extraverted traits such as assertiveness, leadership, and grandiosity,

- antagonistic narcissism represented limited agreeableness, including deceit, distrust, or limited empathy, and

- neurotic narcissism, manifesting as hypersensitivity and shame, for example.

Agentic narcissism tends to correspond to grandiosity, neurotic narcissism tends to correspond to vulnerability, and antagonistic narcissism tends to correspond to both grandiosity and vulnerability (Miller et al., 2021; Weiss et al., 2019). This premise, therefore, shows how the five-factor model coalesces with the distinction between grandiose narcissism and vulnerable narcissism.

Correlates of agentic, antagonistic, and neurotic narcissism

Agentic, antagonistic, and neurotic narcissism also seem to affect the emotions that people experience. For example, in one study that Rogoza, Rogoza, et al. (2025) conducted, Polish adults completed two sets of measures. First, to assess narcissism, participants indicated the extent to which 41 adjectives depict their characteristics. These adjectives were derived from the

- Narcissistic Grandiosity Scale (Crowe et al., 2016) to measure agentic narcissism and included words like brilliant, glorious, powerful, and prestigious,

- Narcissistic Antagonism Scale (Rogoza, Baran, et al., 2025) and included words like abusive, nasty, exploitative, and depreciating,

- Narcissistic Vulnerability scale (Crowe et al., 2018) and included words like ignored, resentful, misunderstood, and underappreciated.

Second, to assess trait emotions, participants completed the Differential Emotions Scale (see Izard, 1992), in which they specified the frequency with which they experience 12 emotions in daily life. These emotions can be classified into agentic emotions, such as interest and joy, antagonistic emotions, such as anger and contempt, as well as neurotic emotions, such as sadness, fear, shame, and guilt. Finally, to assess state emotions, participants indicated, once a night across seven days, the degree to which they experienced these emotions during the day. To analyse the data, the researchers explored the correlations between narcissism and emotions as well as conducted Dynamic Structural Equation Modeling (Asparouhov et al., 2018). These analyses revealed that

- agentic narcissism was positively associated with both agentic emotions as well as antagonistic emotions,

- antagonistic narcissism was positively associated with antagonistic emotions,

- neurotic narcissism was positively associated with both neurotic emotions as well as antagonistic emotions,

- if participants reported agentic narcissism, neurotic emotions did not last over multiple days; if participants reported neurotic narcissism, unpleasant emotions did last over multiple days.

These results are consistent with the premise that all variants of narcissism tend to elicit antagonistic feelings, such as contempt, but only agentic narcissism elicits agentic emotions and only neurotic narcissism elicits neurotic emotions.

Shortened variants of the Five-Factor Narcissism Inventory

A few years later, Sherman et al. (2015) designed and validated a shortened version of this instrument, comprising 60 items but assessing the same 15 facets (for a German version, see Jauk et al., 2023). To validate this instrument, the researchers administered the tool to distinct samples, including undergraduate students, a clinical sample, and users of Amazon Mechanical Turk. In general, compared to the original version, the shorter version generated similar correlations with personality, grandiose narcissism, vulnerable narcissism, and other psychopathologies.

Subsequently, West et al. (2021) constructed and substantiated the most concise version of the five-factor narcissism inventory. This version comprises one item for each of the 15 facets. To construct this version, four samples of participants—591 users of Amazon Mechanical Turk, another 633 users of Amazon Mechanical Turk, 1009 psychology students from one American university, and 408 students from another university—completed the shortened version of the Five-Factor Narcissism Inventory as well as other measures of narcissism. Next,

- the researchers subjected the responses to factor analysis—a factor analysis that uncovered three factors, corresponding to agentic, antagonistic, and neurotic narcissism respectively,

- the researchers then extracted the item from each facet that loads highest on the corresponding factor.

Four of the items correspond to agentic narcissism:

- “I am comfortable taking on positions of authority”, to measure authoritativeness,

- “I often fantasise about having lots of success and power”, to measure grandiose fantasies,

- “I aspire for greatness”, to gauge acclaim-seeking,

- “I love to entertain people”, to assess exhibitionism

Eight of the items correspond to antagonistic narcissism:

- “When someone does something nice for me, I wonder what they want from me”, to measure distrust,

- “I don’t worry about others’ needs”, to assess limited empathy,

- “I’m pretty good at manipulating people”, to gauge manipulativeness,

- “I hate being criticised so much that I can’t control my temper when it happens”, to measure reactive anger,

- “I will try almost anything to get my ‘thrills’”, to gauge thrill-seeking,

- “I do not waste my time hanging out with people who are beneath me”, to measure arrogance,

- “It may seem unfair, but I deserve extra, such as attention, privileges, or rewards”, to assess entitlement,

- “I’m willing to exploit others to further my own goals”, to measure exploitation.

Finally, three of the items correspond to neurotic narcissism:

- “When people judge me, I just don’t care”, to gauge indifference—an item that is inversely associated with neurotic narcissism,

- “I feel ashamed when people judge me”, to measure shame, and

- “I wish I didn’t care so much about what others think of me”, to gauge need for admiration.

The findings confirmed the validity of this instrument. For example, both this instrument, comprising 15 items, and the longer variant, comprising 60 items, produced similar correlations with other measures of narcissism.

Narcissism prototype similarity scores or counts

Rationale

To estimate levels of narcissism as well as other personality disorders, some researchers extract relevant data from established personality inventories. Specifically, researchers have conducted a sequence of four activities to develop this approach:

- First, researchers invited specialists in narcissism to estimate the degree to which each facet of a personality test, such as the NEO Personality Inventory-Revised, coincides with narcissistic personality disorder.

- Second, participants completed the personality test.

- Third, to estimate the degree to which each participant is narcissistic, researchers summed the average response of this person on each of the relevant facets.

- Finally, to validate this approach, researchers have examined the extent to which these estimates of narcissism are correlated with other established measures of this trait.

Which facets of personality epitomise narcissism?

Lynam and Widiger (2001) conducted a study to ascertain which facets of personality tend to epitomise the various personality disorders, including narcissistic personality disorder. Specifically,

- the researchers identified 197 academics who specialise in one or more personality disorders,

- these specialists then rated the degree to which each of the 30 facets of personality, as defined by Costa and McCrae (1992), characterise a typical person who exhibits a specific personal disorder—a disorder in which they are an expert,

- the specialists utilised a five-point scale, ranging from 1 to 5,

- to assist these specialists, two to four adjectives delineated each pole of the facet; for example, fearful and apprehensive versus relaxed, unconcerned, and cool exemplified the facet anxiousness.

As the ratings showed, when the specialists rated the degree to which these facets coincide with narcissism,

- four facets exceeded a mean of 4 and were thus deemed as high in narcissists: these facets comprised anger hostility, assertiveness, excitement seeking, and openness to actions,

- nine facets were lower than a mean of 2 and were thus deemed as especially limited in narcissists: these facets comprised self-consciousness, warmth, openness to feelings, trust, straightforwardness, altruism, compliance, modesty, and tendermindedness (Lynam & Widiger, 2001).

Scores that represent these facets

Subsequently, Miller et al. (2004) derived a measure of narcissism from these 13 facets. To illustrate, in one of their studies, 94 participants, all of whom were undergoing assessment or treatment at a health facility that was affiliated with the University of Iowa, completed the NEO Personality Inventory-Revised. To estimate the degree to which these participants were narcissistic, the researchers

- summed the scores that correspond to the four facets that tend to be high in narcissistic people, such as anger hostility and assertiveness,

- summed the scores that correspond to the nine facets that tend to be low in narcissistic people, such as altruism, and then subtracted this aggregate from the maximum possible value—equivalent to reverse scoring,

- summed these two answers.

Similarly, the researchers applied an analogous procedure to estimate the extent to which these participants exhibited other personality disorders, such as borderline or paranoid. The ensuing values are sometimes called prototype similarity scores or personality disorder counts.

To validate this approach, all participants were subjected to the Structured Interview for DSM-IV Personality Disorders, or SIDP-IV (Pfohl et al., 1997). This interview is designed to assess a range of signs and symptoms of mental health disorders. As Miller et al. (2004) revealed,

- estimates of the personality disorders, as derived from the NEO, were highly correlated with estimates derived from the interview

- that is, for almost all personality disorders, including narcissism, these correlations exceeded .05 (for norms and further evidence of validity, see Miller et al., 2008).

Communal narcissism

Background

People who exhibit grandiose narcissism tend to inflate their capabilities, achievements, and importance. In general, however, they are not as likely to inflate the degree to which they are moral or helpful. That is, they generally exaggerate qualities that are labelled as agentic—their abilities, contributions, and power, for example—rather than qualities that are labelled as communal—such as their morality, kindness, or altruism. To illustrate, people who exhibit narcissism

- tend to perceive themselves as better than average on agentic qualities but not communal qualities (Campbell et al., 2002),

- tend to associate themselves with strong agentic traits but not strong communal traits, as gauged by an implicit association test (Campbell et al., 2007).

However, Gebauer et al. (2012) showed that a portion of grandiose narcissists inflate their communal attributes, such as their morality and altruism—either instead of their agentic qualities or in addition to their agentic qualities. That is, like people who inflate agentic qualities, people who inflate their communal qualities are still motivated to boost their status as soon as possible. However, to boost their status people who inflate their communal qualities like to demonstrate they are more helpful, kind, trustworthy, just, and altruistic than other individuals.

The communal narcissism inventory

To demonstrate this possibility, Gebauer et al. (2012) constructed and validated a scale that gauges this communal narcissism. Participants specify the degree to which they agree with 16 statements such as

- I am the most helpful person I know

- I am an amazing listener

- I am the most caring person in my social surrounding.

- I am extraordinarily trustworthy

- I will be able to solve world poverty

- I will be famous for increasing people’s well-being.

As their studies revealed, these items correspond to one factor. Furthermore, this measure of communal narcissism was positively associated with agentic narcissism—as measured by the Narcissistic Personality Inventory—with correlations approaching 0.27. More specifically, communal narcissism was positively associated with some facets of the Narcissistic Personality Inventory, such as leadership and authority, but inversely associated with entitlement. The researchers also uncovered some other key insights. For example,

- communal narcissism was not related, or inversely related, to a measure of vulnerable narcissism,

- whereas agentic narcissism was inversely associated with agreeableness, communal narcissism was positively associated with agreeableness,

- otherwise, agentic narcissism and communal narcissism exhibited similar correlations to the other personality traits, such as extraversion, openness to experience, and conscientiousness.

- both agentic narcissism and communal narcissism corresponded to the same motives—such as the pursuit of power, as measured by items like “I find satisfaction in having influence over others” (Riketta, 2008).

The strategies that communal narcissists adopt: The narcissistic sanctity and heroism questionnaire

The strategies that agentic narcissists apply to boost their sense of agency or dominance significantly diverge from the strategies that communal narcissists apply to boost their sense of morality or kindness. For example

- to boost their sense of agency and dominance, agentic narcissists tend to utilise narcissistic admiration, in which they strive to attract respect and admiration, and narcissistic rivalry, in which they strive to denigrate other people,

- in contrast, to boost their sense of morality or kindness, some communal narcissists like to show they are virtuous, saintly individuals, who are empathic and trustworthy, called sanctity,

- other communal narcissists like to depict themselves as important to the community—people who intervene to improve their society and resolve problems, called heroism.

Yet, communal narcissists are seldom, if ever, saintly or heroic. They do not seek the perspectives of other individuals and thus tend to disregard the needs of other people. Instead, they underscore their virtues or display acts of heroism to improve their status.

Żemojtel-Piotrowska et al. (2025) constructed a scale that is designed to assess these two strategies. In particular, the measure of sanctity comprises five items such as

- I have a unique gift for understanding others.

- I am a modest person even though I do many good things for others.

- Everyone knows that I am a completely trustworthy person

The measure of heroism comprises five items such as

- Lots of people admire me for what I do for them.

- I am universally respected for my heroic and steadfast fight against evil.

- Thanks to me, the world is more just.

The researchers administered this scale and a range of other relevant measures to 12 samples of participants, ranging from 169 to 884 adults. Across these samples, the researchers showed that

- the ten items do correspond to the two factors, as hypothesised: the CFI exceeded .9 in every sample,

- both sanctity and heroism were positively associated with a global measure of communal narcissism—the communal narcissism inventory—with correlations exceeding 0.65,

- furthermore, both sanctity and heroism were positively related to some other measures of grandiose narcissism, such as narcissistic admiration and the narcissism grandiosity scale,

- in contrast, sanctity was inversely associated with narcissistic rivalry and vulnerable narcissism, as gauged by the hypersensitivity narcissism scale,

- however, heroism was positively associated with narcissistic rivalry and not significantly associated with vulnerable narcissism.

These findings, especially the association between communal narcissism and grandiose narcissism, suggest that people who demonstrate sanctity and heroism do not only attempt to inflate their communal attributes but also attempt to inflate their agency as well. That is, they strive to display they are both moral as well as capable and successful.

Short measures

Introduction

Measures of narcissism are usually long, typically gauging multiple facets. However, researchers have also developed short measures. These short measures are not as valid or informative but useful in many circumstances such as when

- researchers or practitioners want to measure levels of narcissism in the same people at many times,

- the participants cannot readily concentrate for more than a few seconds, because of personal deficiencies or challenging circumstances.

A single-item measure of narcissism

To illustrate a short measure, Konrath et al. (2014) proposed that one item may be sufficient to assess narcissism, at least to a reasonable extent. Specifically, participants are asked to indicate the extent to which they agree with one statement on a seven-point scale, ranging from not very true of me to very true of me. The statement is “I am a narcissist. Note the term narcissist means egotistical, self-focused, and vain”. Across 11 studies, the researchers discovered that

- responses to this item and responses to the Narcissistic Personality Inventory, one of the longest measures of grandiose narcissism, generated a correlation of .40,

- similarly, responses to this item were positively associated with most of the subscales of this inventory too, such as vanity, exhibitionism, exploitative-ness, authority, superiority, and entitlement.

- the correlation between responses to this item and a measure of social desirability bias was modest, at r = -23.

- whereas the Narcissistic Personality Inventory was positively associated with irritability and hostility, the single-item measure was also positively associated with shame and fear; accordingly, only the single-item measure appears to coincide with both grandiosity and vulnerability,

- response to this item at one time and responses to this item ten days later generated a correlation of .79, indicating excellent stability over time,

- responses to this item were positively associated with extraversion and inversely associated with agreeableness.

A short measure of agentic narcissism: Narcissistic Grandiosity Scale

As research on the five-factor model of narcissism has identified, narcissistic tendencies can be divided into three main dimensions: agentic narcissism, partly associated with features of extraversion, antagonistic narcissism, associated with features of low agreeableness, and neurotic narcissism, partly associated with features of neuroticism. Crowe et al. (2016) validated a short measure, called the Narcissistic Grandiosity Scale, to gauge one of these dimensions: agentic narcissism. Specifically, participants rate, on a 9-point scale, the extent to which they demonstrate six adjectives: glorious, prestigious, acclaimed, prominent, high-status, and powerful. As evidence of validity, agentic narcissism, as gauged by these six adjectives, was

- strongly associated with traits that correspond to the DSM V, such as antagonism, grandiosity, attention seeking, and callousness, as measured by the Personality Inventory for DSM–5 (Krueger et al., 2012),

- strongly related to low levels of agreeableness and high levels of extraversion, as measured by the NEO personality inventory revised,

- strongly associated with other measures of grandiose narcissism but only modestly or negligibly associated with measures of vulnerable narcissism.

A short measure of antagonistic narcissism

Similar to the short measure of agentic narcissism, Rogoza, Baran, et al. (2025) developed a short measure of antagonistic narcissism. To complete this scale, participants specify, on a 9-point scale, the degree to which various adjectives, such as abusive or nasty, describe their character or inclinations. Although the scale usually comprises 18 adjectives, Rogoza, Baran, et al. (2025) revealed that researchers could administer a scale that comprises only four adjectives—abusive, nasty, exploitative, and depreciating—to gauge state narcissism. To illustrate, in one study, every day, over a month, 317 adults indicated the extent to which they perceived themselves as

- abusive, nasty, exploitative, and depreciating to measure antagonistic narcissism,

- brilliant, glorious, powerful, and prestigious to measure agentic narcissism,

- ignored, resentful, misunderstood, and underappreciated to measure neurotic narcissism.

As a multilevel confirmatory factor analysis revealed (Lüdtkeet al., 2007), each set of adjectives were indeed related to three distinct factors. This study thus confirms these 12 items represent three distinct characteristics, labelled as antagonistic, agentic, and neurotic narcissism, respectively.

A short measure of neurotic narcissism

Like the short measure of agentic narcissism, Crowe et al. (2018) also designed and validated a short measure of neurotic narcissism, called the Narcissistic Vulnerability scale. To complete this scale, participants indicate, on a 9-point scale, the degree to which 11 adjectives—ashamed, ignored, self-absorbed, fragile, underappreciated, envious, resentful, insecure, irritable, misunderstood, and vengeful— describe their character or inclinations. In one study, the researchers administered an even shorter version, comprising 6 items: underappreciated, envious, resentful, insecure, misunderstood, and ignored. To validate these measures, the researchers then recruited three samples of participants and administered a range of scales. Overall, these studies revealed that

- the Narcissistic Vulnerability scale was negatively associated with agreeableness and extraversion but positively associated with neuroticism, as measured by the mini-IPIP measure of personality (Donnellan et al., 2006),

- the Narcissistic Vulnerability scale was positively and strongly associated with other measures of vulnerable narcissism, such as the Hypersensitive Narcissism Scale,

- the 11 adjectives correspond to one factor, in which the CFI = .95 and standardised root-mean-square residual is .034.

Measures of specific facets of narcissism

The Psychological Entitlement Scale

One of the core features of narcissism revolves around entitlement. One facet of most established measures of narcissism, especially grandiose narcissism, revolves around entitlement. However, some measures assess entitlement only. For example, Campbell et al. (2004) designed and validated a scale called psychological entitlement. The measure comprised nine items, such as

- I honestly feel I am just more deserving than others.

- Great things should come to me.

- If I were on the Titanic, I would deserve to be on the first lifeboat!

- I demand the best because I’m worth it.

- I do not necessarily deserve special treatment [reverse-scored]

- I deserve more things in my life.

- People like me deserve an extra break now and then.

- Things should go my way.

- I feel entitled to more of everything

Campbell et al. (2004) published a series of nine studies to validate this measure. These studies corroborated the reliability and validity of this scale. For example

- this measure of entitlement was not significantly associated with a measure of social desirability—the Balanced Inventory of Desirable Responding (Paulhus, 1991)—implying that people who want to depict themselves favourably may still concede they are entitled,

- this measure of entitlement was only modestly associated with the entitlement subscale of the Narcissistic Personality Inventory, suggesting this measure is not redundant,

- the correlation between scores on this measure one day and scores on this measure two months later approximate 0.7, suggesting the responses are consistent over time, and

- this measure of entitlement is inversely associated with agreeableness and emotional stability but, unlike the Narcissistic Personality Inventory, is not significantly associated with extraversion.

Perhaps more interestingly, this measure also predicted a range of problems that entitled people may experience. To illustrate

- this measure of entitlement predicted which university students, from the University of Georgia, would grab more a large handful of candy when offered, even when told this candy was actually intended for children,

- this measure of entitlement predicted which participants believed they deserve a higher salary,

- this measure of entitlement predicted which individuals would experience problems in relationships, such as limited empathy, respect, and perspective-taking.

According to Campbell et al. (2004), this measure of entitlement circumvents some problems that researchers experience when they apply other tools, such as the Narcissistic Personality Inventory, to gauge entitlement. To illustrate, the subscale of entitlement in the Narcissistic Personality Inventory comprises some items that assess dominance rather than entitlement, can generate a low alpha reliability, and is not always differentiated from other subscales in factor analysis (e.g., Emmons, 1984).

Other measures of entitlement

Researchers have raised one concern about the psychological entitlement scale that Campbell et al. (2004) developed. Some of the items do not translate to other languages or cultures well. For example, references to the Titanic may not be meaningful to all cultures. Similarly, some phrases, such as “deserve an extra break now and then” cannot be readily translated to some languages.

Because of this concern, Yam et al. (2017) constructed a shorter measure of entitlement, comprising only four items. Specifically, Yam et al. distilled each item of the psychological entitlement scale that could be translated into Mandarin. These items were

- I honestly feel that I am just more deserving than others

- Great things should come to me

- I demand the best because I am worth it

- I deserve more things in my life”.

As evidence of reliability and validity, the Cronbach’s alpha, or internal consistency, of this scale was .93, indicating the items are highly correlated with each other. Furthermore, psychological entitlement was positively associated with both interpersonal deviance, such as mocking a colleague, and organisational deviance, such as stealing property from work.

The Hurlbert Index of Sexual Narcissism

Many researchers have also explored manifestations of narcissism in sexual behaviour, called sexual narcissism. That is, sexual narcissism refers to the tendency of some people to inflate their sexual capabilities and to feel they should be granted the right to fulfill their sexual desires. To measure this tendency, researchers often administer the Hurlbert Index of Sexual Narcissism (Hurlbert, 1991; Hurlbert et al., 1994). To complete this scale, participants indicate the degree to which they agree or disagree with 25 items, such as

- I believe I have a special style of making love,

- I think people have the right to do anything they please in sex,

- In certain situations, sexually cheating on a partner is justifiable,

- I think I am better at sex than most people my age,

- I have no sexual inhibitions,

- When it comes to sex, not enough people live in the moment

- Emotional closely can easily get in the way of sexual pleasure.

To validate this scale, Hurlbert et al. (1994) conducted a study in which the participants were men who had completed a workshop on marital enrichment. From this sample, 44 of the participants fulfilled the criteria of narcissistic personality disorder as their primary disorder, as gauged by the Millon Clinical Multiaxial Inventory-II. These participants were compared to 82 participants who did not exhibit the signs of narcissistic personality disorder. Furthermore, all participants completed the Hurlbert Index of Sexual Narcissism as well as

- the sexual opinion survey, to assess the degree to which individuals express positive or negative attitudes towards sex (see Fisher et al., 1988),

- the sex-role ideology scale (Kalin & Tilby, 1978), to measure the extent to which individuals adopt traditional or egalitarian beliefs around sex roles, such as “The first duty of a woman with young children is to home and family” (for additional items, visit this webpage)

- a measure of sexual-esteem, including items like “I would rate my sexual skills quite highly” (Snell & Papini, 1989), gauging the capacity of individuals to relate sexually to their partner,

- a measure of sexual preoccupation, typified by items like “I think about sex all the time” (Snell & Papini, 1989),

- a measure of sexual depression—or the degree to which individuals feel disappointed with sexual facets of their relationship, exemplified by items like “I feel down about my sex life” (Snell & Papini, 1989).

As hypothesised, relative to the other participants, the individuals who fulfilled the criteria of narcissistic personality disorder did indeed report elevated levels of sexual narcissism. Thus, sexual narcissism does seem to be a feature of narcissism, at least in men. In addition, the participants who exhibited narcissistic personality disorder were more likely to report negative attitudes towards sex, traditional beliefs about the role of women, and a higher sexual self-esteem, perhaps emanating from their tendency to inflate their capabilities. Sexual preoccupation was higher in the narcissistic men, but this difference did not reach significance (p = .064).

The Sexual Narcissism Scale

Widman and McNulty, two academics at the University of Tennessee, developed an alternative measure of sexual narcissism in 2010: the Sexual Narcissism Scale. One benefit of this instrument is that sexual narcissism is divided into four subscales:

- sexual exploitation, corresponding to items like “One way to get a person in bed with me is to tell them what they want to hear”,

- sexual entitlement, corresponding to items like “I am entitled to sex on a regular basis”,

- low sexual empathy, corresponding to items like “The feelings of my sexual partners

- don’t usually concern me”,

- and a grandiose sense of sexual skill corresponding to items like “I am an exceptional sexual partner”.

To validate these sub-scales, Widman and McNulty (2010) administered this measure to 299 college students, enrolled in psychology. Confirmatory factor analysis on the final scale, comprising only 20 items, validated the four factors, in which CFI = .95, SRMR = .077, and RMSEA = .077 (to interpret these indices, see Bentler, 1990; Kline, 2005; Browne & Cudeck, 1993 respectively). The model was applicable to both men and women.

The four sub-scales were positively associated with each other, except low sexual empathy was inversely associated with sexual skill. Presumably, limited empathy may impede the capacity of individuals to accommodate their partners, compromising sexual skill.

To validate this scale, Widman and McNulty (2010) conducted a second study to ascertain whether these four sub-scales are related to sexual behaviour even after controlling grandiose narcissism in general. In this study, 415 undergraduate men completed the Sexual Narcissism Scale as well as the Narcissistic Personality Inventory: a measure of grandiose narcissism. Finally, participants completed an adapted version of the Sexual Experiences Scale (Abbey et al., 2005). This measure

- ascertains the degree to which individuals have perpetrated acts of sexual aggression since the age of 14,

- gauges a range of acts such as pressure or lies to encourage sex, exploitation of intoxicated women, and sexual acts that were unwanted by the woman,

- generates three indices: unwanted sexual contact, sexual coercion, and attempted or completed rape.

An analysis of correlations revealed that all four sub-scales of sexual narcissism were positively associated with unwanted sexual contact or sexual coercion. In addition, exploitation and entitlement were positively related to rape. Overall, sexual narcissism was positively associated with sexual aggression even after controlling grandiose narcissism. In contrast, after controlling sexual narcissism, grandiose narcissism was not positively associated with sexual aggression. Yet, sexual narcissism and grandiose narcissism were positively related to each other (r = .44)

Narcissism in particular settings

Narcissism at work

Some researchers have developed instruments that assess narcissism as well as other dark traits, including Machiavellianism, psychopathy, and sadism, in particular settings. For example, Thibault and Kelloway (2020) designed and validated a measure of these traits that is applicable to workplaces. To gauge narcissism, the instrument comprised the following items:

- My position at work is prestigious.

- I am much more valuable than my coworkers.

- I demand respect at work.

- People always pay attention to me at work.

- Others admire me at work.

- I like being the centre of attention at work.

The instrument also included a measure of

- Machiavellianism, such as “At work, people are only motivated by personal gain”,

- psychopathy, such as “I don’t care if I accidently hurt someone at work.”, and

- sadism, such as “It’s funny to watch people make mistakes at work”.

Thibault and Kelloway (2020) conducted two studies to validate this instrument. As these studies revealed

- a confirmatory factor analysis validated the four factors,

- all these traits were significantly associated with workplace deviance, such as bullying, incivility, and other counterproductive acts, even after controlling social desirability.

Narcissism seems to be positively associated with affective commitment towards the organisation. Nevertheless, as the authors underscored, people who are narcissistic may inflate the degree to which they perceive their job as prestigious and significant, increasing the likelihood they may inflate this commitment but still leave if they do not receive the respect they believe they deserve.

Narcissism in leaders and supervisors

Zhang et al. (2024) constructed a set of six items that assess the degree to which staff perceive their supervisor or leader as narcissistic, such as

- My superior is a self-centred person

- My leader often boasts about himself in front of us

- My leader will not help others unless they get double or more in return

- My leader wants to be the focus no matter what the situation

As evidence of reliability and validity

- Cronbach’s alpha for this scale was .85,

- when subjected to a factor analysis, all standardised loadings exceeded .80 and the average variance extraction exceeded 0.7.

The items appear to correspond more to grandiose narcissism than vulnerable narcissism. Nevertheless, the authors did not clarify how the items were chosen or constructed. ssistic may inflate the degree to which they perceive their job as prestigious and significant, increasing the likelihood they may inflate this commitment but still leave if they do not receive the respect they believe they deserve.

Measures of narcissism in children, adolescents, and parents

The Narcissistic Personality Questionnaire for Children-Revised

Previously, research on the features, consequences, and causes of narcissism was primarily confined to adult participants. In more recent decades, some research has been extended to children and adolescents. Accordingly, researchers have developed measures of narcissism that are more applicable to children and adolescents. Initially, these researchers adapted the Narcissistic Personality Inventory, the most common measure of grandiose narcissism, to suit children and adolescents. These adapted instruments comprised fewer questions and referred to circumstances that are more applicable to individuals under 18. Examples of these measures include the

- Narcissistic Personality Inventory-Juvenile Offender (Calhoun et al. 2000),

- Narcissistic Personality Inventory-Children (Barry et al. 2003).

Because of some concerns around the length and factor structure of these instruments, Ang and Yusof (2006) developed the Narcissistic Personality Questionnaire for Children. To complete this measure, the children indicate the degree to which 18 statements describe their beliefs and behaviours on a 5-point Likert scale. This instrument comprises four facets:

- six items, such as “I am really a special person”, gauge superiority,

- six items, such as “If I ruled the world, it would be a better place”, gauge exploitative-ness,

- three items, such as “I like it when others brag about the good things I have done”, measure self-absorption, and

- three items, such as “It does not matter if I am the leader or not” (reverse-scored), measure leadership.

Nevertheless, Ang and Raine (2008) raised several concerns about this measure. First, alpha reliability of self-absorption and leadership are less than 0.7 and thus inadequate. Second, leadership and, to a lesser extent, self-absorption were deemed to be adaptive in some circumstances and not applicable to the intent of this measure. Consequently, Ang and Raine (2008) proposed the Narcissistic Personality Questionnaire for Children-Revised—an instrument that is identical to the Narcissistic Personality Questionnaire for Children, except the items that correspond to self-absorption and leadership were deleted. The six items that measure superiority are

- I always know what I am doing.

- I am going to be a great person.

- I was born a good leader.

- I am really a special person.

- I think my body looks good.

- I think I am a great person.

The six items that measure exploitative-ness are

- If I ruled the world it would be a better place.

- I am good at getting people to do things my way.

- It is easy for me to control other people.

- I would do almost anything if you dared me.

- I can make people believe anything I want them to.

- When I am supposed to be punished, I can usually talk my way out of it.

This revised variant is usually preferred to the original version. Specifically, as Ang and Raine (2008) revealed

- the 12 items correspond to two factors that generate adequate alpha reliability—and this factor structure is invariant across age and gender,

- overall narcissism, derived after the two sub-scales are combined, was more strongly related to proactive aggression than reactive aggression.

The Childhood Narcissism Scale

Around the same year the Questionnaire for Children-Revised was released, Thomaes et al. (2008) published the Childhood Narcissism Scale. This scale comprises only 10 items and one facet. Specifically, participants specify, on a 4-point rating scale, ranging from not at all true to completely true, the degree to which 10 statements characterise their beliefs and behaviour. Typical items include

- I think it’s important to stand out.

- Kids like me deserve something extra.

- Without me, our class would be much less fun.

- It often happens that other kids get the compliments that I actually deserve.

- I love showing all the things I can do.

As evidence of validity, scores on this measure of narcissism were positively associated with

- the degree to which self-esteem depends on the validation of other people, called self-esteem contingency, such as “When other kids like me, I feel happier about myself” (Rudolph et al., 2005),

- the extent to which the interpersonal goals of these individuals revolve around dominance, admiration, or agency, such as “…How important is it for you that the others respect and admire you?”, rather than collaboration and belonging, such as “…how important is it for you that real friendship develops between you?” (Ojanen et al., 2005),

- limited levels of empathy, as rated by peers in the classroom to items like “These kids feel bad if they see another kid without a friend to play with” (Strayer & Roberts, 2004), and

- an inclination to seek revenge, as rated by peers.

Narcissism Scale for Children: Introduction

Before 2019, measures of narcissism in children did not explicitly differentiate grandiose narcissism from vulnerable narcissism. To address this shortfall, in 2019, three academics, Derry et al., employed at the University of Western Australia, constructed and validated the narcissism scale for children. The scale comprises 15 items. Seven of the items measure grandiose narcissism—or the degree to which children strive to inflate their qualities, achievements, and significance—including

- I have always known I am more special than most kids,

- I can talk my way out of anything,

- I am probably going to be rich one day,

- I can tell what adults are thinking,

- I like to show off all the things that I do well.

Eight of the items measure vulnerable narcissism—or the extent to which children are especially sensitive to criticism or susceptible to shame and envy—including

- I get jealous if other kids get more than me,

- When other people don’t notice me, I feel like I’m worth nothing,

- I feel angry and ashamed when I get told off,

- I have enough to do without having to do things for others,

- No one understands when I am upset.

Narcissism Scale for Children: Validation studies

Derry et al. (2019) conducted four studies to validate this instrument. For the first three studies, the samples comprised 224 children, 122 children, and 137 children respectively, all aged between 8 and 12. In each study, the participants completed the narcissism scale for children as well as a suite of other measures. Overall, the findings validated the instrument. Specifically

- in the first study, confirmatory factor analysis substantiated the two factors, TLI = 0.93, CFI = 0.95, SRMR = 0.04, RMSEA = 0.04,

- Cronbach’s alpha for grandiose narcissism and vulnerable narcissism respectively were .74 and .80,

- grandiose narcissism and vulnerable narcissism were positively related to one another,

- vulnerable narcissism, but not grandiose narcissism, was positively associated with emotional symptoms, such as a temper, as gauged by the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (Goodman, 1997),

- however, both grandiose narcissism and vulnerable narcissism tended to coincide with conduct problems, hyperactivity, and limited prosocial behaviour, also measured by the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire,

- vulnerable narcissism, but not grandiose narcissism, was positively associated with fear of evaluation (La Greca & Stone, 1993),

- both grandiose narcissism and vulnerable narcissism were positively related to a need for approval, as gauged by the Need for Approval Questionnaire (Rudolph et al., 2005),

- as the third study revealed, the test-retest correlation over 6 months was .68 for grandiose narcissism and .70 for vulnerable narcissism.

For the final study, the sample comprised 137 adolescents, aged between 13 and 17. The pattern of results observed in children generally, but not entirely, extended to adolescents. To illustrate some of the disparities

- vulnerable narcissism was not significantly associated with conduct problems or hyperactivity in adolescents,

- factor analyses suggested that both grandiose narcissism and vulnerable narcissism could perhaps be divided into two subscales, differentiating interpersonal behaviours and intrapersonal experiences, although this model was not deemed as reliable.

Perceived maternal narcissism scale

In 2023, Alpay and Aydın, two academics from Mersin University in Türkiye, constructed and validated a scale that measures the degree to which individuals perceive their mother as narcissistic, called the perceived maternal narcissism scale. The scale comprises 23 items, divided into five subscales. The five subscales, coupled with a sample item, are

- limited empathy (e.g., “She did not like me to disclose my negative emotions”),

- criticism (e.g., “It was easy to please her”),

- grandiosity (e.g., “She liked to be the focus of the topics that were spoken”),

- manipulation (e.g., “I would feel like she was trying to control me”), and

- parentification (e.g., “I would do what she was supposed to do as a parent”).

To design this instrument, the researchers first adapted some of the items that are embedded in standard measures of narcissism, such as the Pathological Narcissism Inventory. Second, the researchers derived items from models that delineate the features and determinants of narcissistic families (e.g., Donaldson-Pressman & Pressman, 1994). To validate the perceived maternal narcissism scale, 316 adults completed this measure as well as the Perceived Parenting Attitudes in Childhood – Short Form (Arrindell et al., 1999) to gauge emotional warmth, overprotective behaviour, and parental rejection. In addition, 71 participants completed the measures twice, separated by three weeks. As this study revealed

- confirmatory factor analysis substantiated the five distinct facets: RMSEA = 0.058, CFI = 0.91, GFI = 0.85, and NNFI = 0.90,

- Cronbach’s alpha exceeded 0.7 for each subscale and was 0.92 for the total score,